Second in a series on a recent visit to Louisiana’s bayous, a trip sponsored by the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, to start a conversation between people there who are being flooded out and those in the Down East communities of Carteret County who face similar threats.

BAYOU LAFOURCHE, La. – Eric Verdin clearly knew where he was going. These waters are like family, after all, but his GPS plotter was frantic. Using the latest marine charts, its line tracing our path on the screen in front of us blinked red, warning us that we were about to plow into dry land. It was a good time, it seemed to suggest, to ABANDON SHIP. But we had open seas ahead of us and 8 feet of water under our keel.

Supporter Spotlight

“There used to be an orange grove here,” our captain conceded with a shrug.

Not a hundred years ago. Not 50. Not even 20. “Not that long ago, really,” Verdin said, as he looked out the window of the shrimp boat’s pilot house across the placid water of the bayou to the glimmering Gulf of Mexico on the horizon. “Just about all that water you see in front of us was all marsh.”

His native people, the Biloxi-Chitimacha, have lived on the fringes of this watery world along the southwestern tip of Louisiana for many generations. Verdin, 58, has known these waters since boyhood. He makes his living here, first running big boats to supply the oil rigs out in the Gulf and now chasing brown and white shrimp. He’s witnessed changes he never thought possible. “I’ve seen the absolute devastation of our coast during my lifetime,” he said with a sigh. “Miles and miles of marsh are now open waters.”

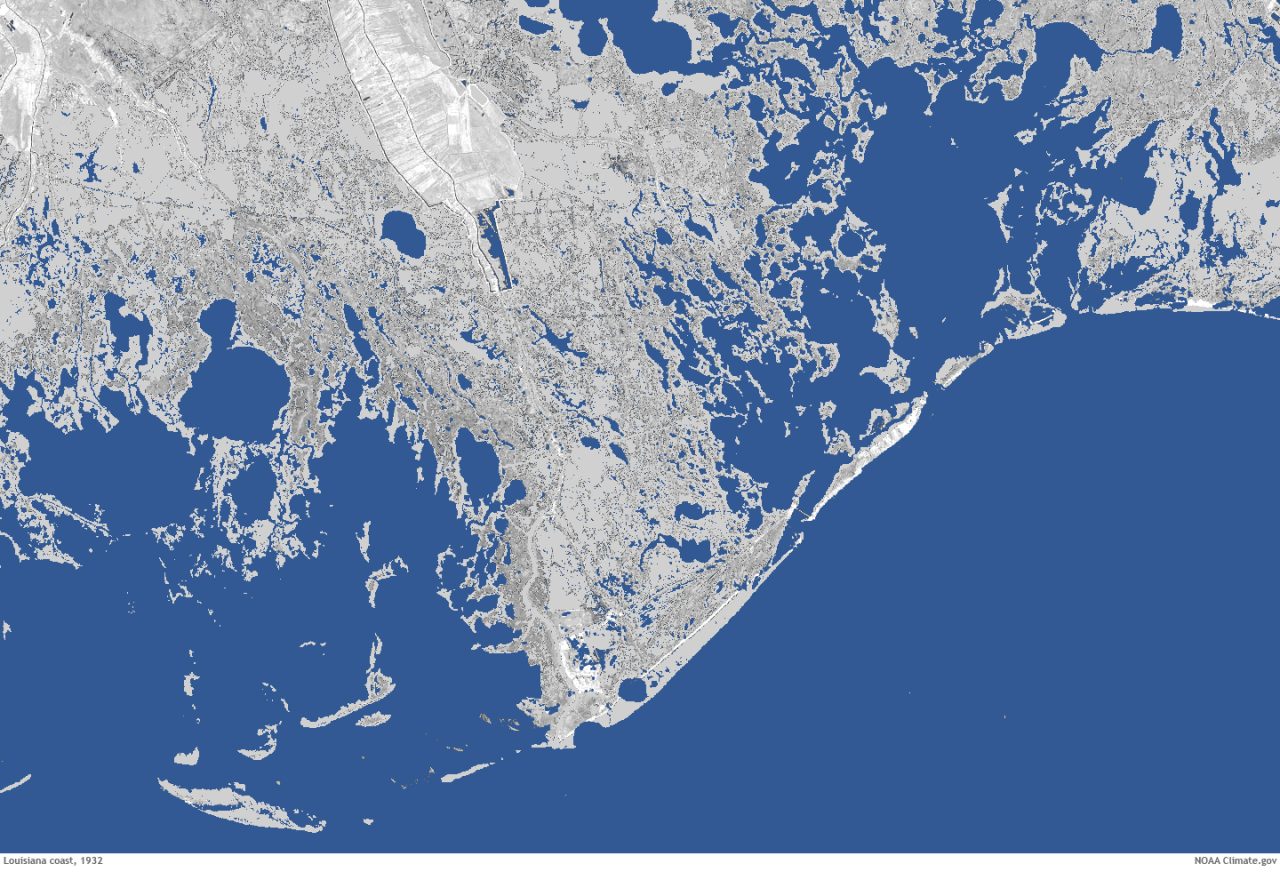

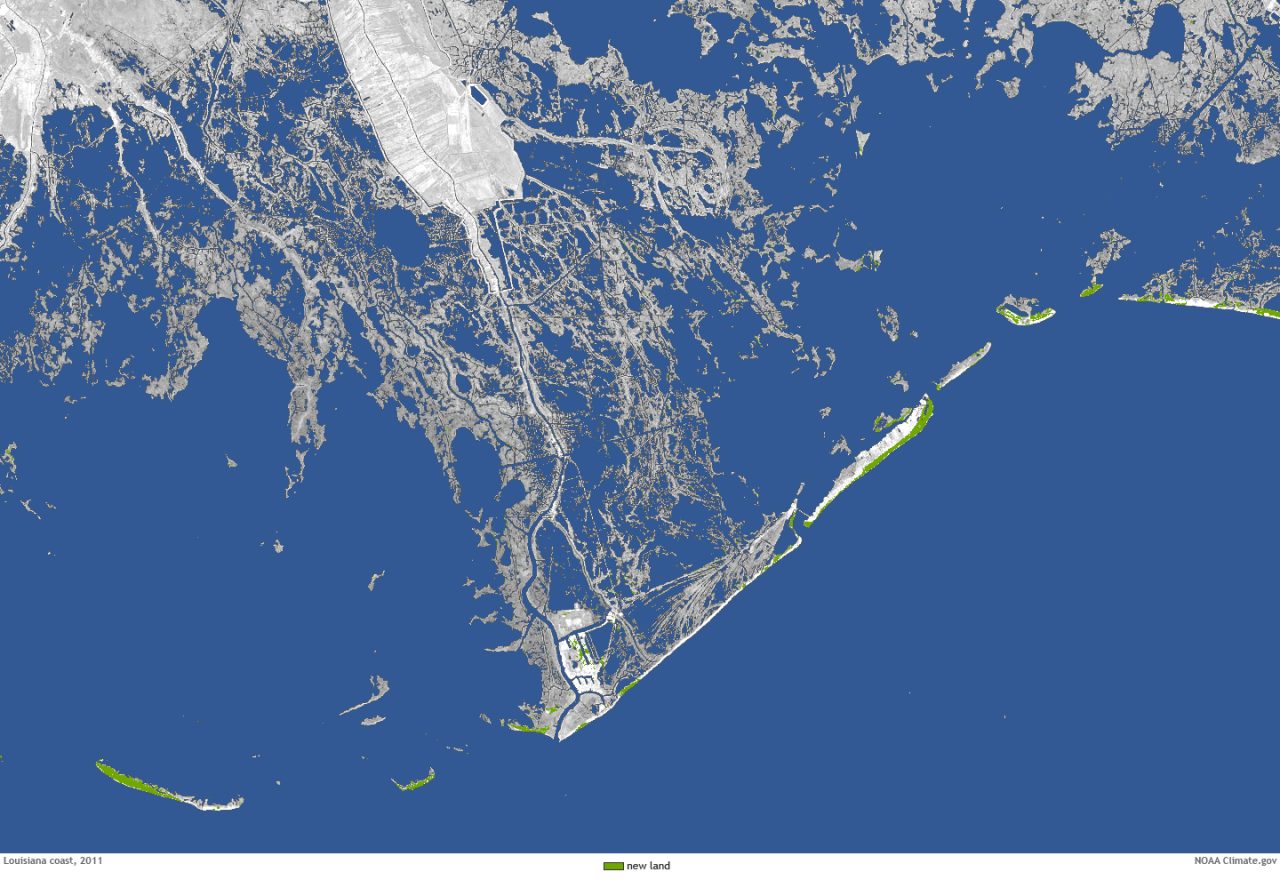

Nowhere on Earth does land disappear as quickly as it does here in southern Louisiana. According to one fantastic estimate, the water covers, on average, a chunk of marsh the size of a football field every hour or so. Or is it 15 minutes? No matter. The change is so rapid that not even online navigation charts can keep up. Brought about by a catastrophic combination of human engineering, ignorance and hubris, it’s been going on, though more slowly, for at least a century. During that time, an area of marshland the size of Delaware vanished. Now, add another human-induced insult — rising seas triggered by the warming climate — and a similar-sized piece is expected to disappear in just 25 years.

This is ground zero for sea level rise and wetland loss in the world. We, of course, had to see it ourselves.

Supporter Spotlight

A group of North Carolinians, on a 10-day trip sponsored by Duke University, toured coastal Louisiana in June looking for connections, for people at the water’s edge who are facing the perils wrought by a rapidly changing environment. They have weathered the frequent storms, survived the destructive aftermaths, and found ways to accommodate the rising seas as the familiar natural world transforms in the blink of their lifetimes. Some of their communities have been displaced, and their cultures are threatened.

Coastal people back home will soon increasingly confront the same dangers, knows Karen Amspacher, a native of Harkers Island in Carteret County, the director of a cultural museum there and the group’s inspirational leader. “We’re all living on the edge,” she told Verdin after he welcomed us aboard his 55-foot shrimper, Lil’E. “I’ve been trying to find common ties with people who are going through what we will.”

After the bayous of Louisiana and Florida’s Gold Coast, the uniformly flat North Carolina coastal plain is the most-endangered landscape in America. The small fishing and farming villages of low-lying eastern Carteret County, Amspacher’s beloved Down East, face a grim future of increasing storms and flooding. Many of the homes will become uninhabitable by century’s end.

Jerrica Cheramie understands all too well the fears that the people there will have to confront. “I’m just 36 and I’ve seen all this change,” said the local high school teacher who joined us on the boat. “It’s terrifying.”

Taming A River

Since its beginning, the Mississippi River has deposited the silt of a continent to build the Louisiana coastline. Its delta, a water-logged labyrinth of bayous, marsh grasses and ancient cypress trees, fans out like a swampy snout into the Gulf. The first European settlers along the lower Mississippi in the 18th century started throwing up dirt walls along the river’s banks to protect themselves from the frequent floods. The effort intensified a century later after a series of devastating deluges. Congress got involved after the Great Flood in 1927 killed 500 people and inundated 27,000 square miles. It authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to begin digging. That old river man, Mark Twain, once scoffed at the notion of containing the mighty Mississippi. “Ten thousand River Commissions …,” he wrote, “cannot tame that lawless stream … cannot say to it, ‘Go here,’ or ‘Go there,’ and make it obey.”

By God, they tried, and they came damn close. Close enough, anyway, to make southern Louisiana disappear.

Today, massive levees line the river for about half of its 2,400-mile-long route to the sea. Along the very southern leg of its journey, the Mississippi is little more than a big canal, hemmed in place by huge earthen walls.

We followed it one day for its last 75 miles. Down Louisiana Highway 23 we went, through Bohemia and Port Sulfur, past Home Place and Triumph, to Venice, population 164. It’s as far as you can go by car. The river was on our left the entire way, but it flowed unseen behind its wall. The smokestacks of the ships we passed were the only hints that the river was actually there. At the end of the road, we had hoped to watch the great Mississippi make its last, lumbering lurch to the Gulf. Alas, there was nothing to see but more marsh, the wall and assorted bits of industrial detritus – cranes, barges, pipes, barrels and such. More on that shortly.

As we stood at the end of the road expressing our disappointment, a set of eyes popped up through the murky water of a lagoon that wasn’t 20 feet away. Then, another. Soon, it was a dozen. Then, more. I had never seen so many alligators in one place at a time, and I once lived in Miami and fished the Everglades in a canoe. They all came toward us, gliding silently through the water, leaving gentle wakes behind them. Our presence clearly triggered this conclave. Other gawkers, we surmised, had also come this way and had fed the native wildlife. The approaching gators were expecting a handout. What tidbits do you toss to giant reptiles? I wondered as we quickly headed back to the cars. A bucket of Col. Sanders? A Big Mac? Chick-fil-A nuggets, we agreed. Everything likes them.

After that meander worthy of the old Mississippi, let’s get back on course. The point of all this is that the river now heads straight to the Gulf. No more oxbow cutoffs, no twists, no turns. With it, goes all that muck. Very little now leaks into the surrounding bays. Without sediment to nourish them, the marshes have been sinking for a long time. They are drowning more quickly now as sea level rise accelerates.

Big, Big Oil

Verdin killed the engine and dropped anchor. We bobbed under a scorching sun in languid Lake Raccourci. A lot of open water bodies on the Gulf’s fringes in Louisiana are called lakes because they were surrounded by marsh when the mapmakers named them. To Verdin, these are sacred waters. His son, Eric Jr., died in a car wreck five years ago. He was only 34. His family spread his ashes here, one of his “honey holes.” Verdin named his boat after Eric and put a picture of his smiling son in a frame on the bulkhead behind the ship’s wheel. “He always used to stand behind me and say go this way or that way,” his father explained. Verdin comes back often, especially on the anniversary of his son’s death in December when he places flowers in the water. He couldn’t think of a better place to take visitors. We were honored.

We were also surrounded by an odd array of pipes, pumps and iron platforms that rose out of the water everywhere. Rust was their primary color. Each one marked an oil or natural gas well, Verdin explained, and most are still producing, though some are approaching 100 years old. They are relics, really, of simpler times, when the Gulf was just becoming America’s great oilfield.

Like the deltas of many of the world’s great rivers, the Mississippi’s is full of oil and gas. All that muck that the river deposited for millions of years contained the organic ingredients — ancient plants, algae, bacteria – of oil and gas. They’re called fossil fuels for a reason. Time and heat did the rest.

I sat one night on the beach at Grand Isle, one of the few sandy beaches in the lower bayous, and counted the lights of 22 offshore oil rigs blinking on the horizon. There are more than 600 out there, making the Gulf of Mexico America’s primary source for offshore oil and natural gas.

Big Oil is really big here. Its presence is almost everywhere: Refineries with their fiery tails of methane, mountains of pipeline stacked in neat pyramids, natural gas liquification plants, petrochemical complexes, miles of storage tanks, acres of stacked barrels. All in industrial grimy gray with splashes of white. It ain’t pretty and there’s likely no way to make it so.

From Lake Raccourci, we could see the outline of Port Fourchon, maybe 8 miles away. It is Big Oil’s most important port. More than 400 ships leave it every day to supply the rigs. More than 15,000 people fly out of there every month to work on them. It’s the operational base for almost 300 companies. The port is perched at the tail end of LA1, a vital road so threatened that it’s being raised on a causeway to keep it from slipping under the Gulf.

Before all that, there were these pipes now sticking out of the water. The reservoirs closest to shore were, naturally, the first to be tapped, starting in the 1930s. The companies dug canals through the dense marshland to dig the wells. The channels ended up becoming pathways for water, accelerating the marsh’s demise. Many of the wells are now miles from the nearest dry land.

Everybody understands the role the oil and gas industry played in destroying the marshes, Verdin explained as the shrimp were almost ready for lunch. “In hindsight, it ruined our environment, but you won’t find fishermen around here who are anti-oil.” he said. “We know how much we’ve benefitted. When the fishing was good, we fished. When oil was booming, we worked in oil.”

The Diversion

Verdin spilled the pot of boiled shrimp, corn on the cob and potatoes onto one of the hatch covers, and we dug in. The lunchtime conversation turned to The Diversion, the first step of a grand ecosystem experiment that would have taken 50 years to complete and would have cost more than $50 billion. Officially known as the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, the controversial project intended to divert some of the Mississippi’s flow to allow sediment to once again nourish portions of the marsh. “We need to do something,” Verdin said. “This can’t go on.”

That was the state’s conclusion after Hurricane Katrina devastated the region 25 years ago last month. Healthy marshes, scientists said, would have lessened the damage. In response, the state legislature in 2007 passed the first coastal master plan, a 50-year initiative to blunt the forces eating away at the coastline: sinking land, rising seas, and the channels dug by the oil and gas industry. Barrier islands would be rebuilt, levees bulked up, and structures raised. The plan also endorsed 11 river-diversion projects. The biggest was in Barataria Bay, about 30 miles east of our lunchtime anchorage. Engineers planned to poke a hole into the levee near Ironton in Plaquemines Parish and release 75,000 cubic feet of sediment every second. They estimated that doing so every day for six months a year would create 21 square miles of new marsh in 50 years. “It gives us a fighting chance to win this battle,” Chip Kline, the chairman of the state authority charged with the task, said in 2021.

Others weren’t so sure. Fishermen worried that the sudden influx of freshwater would push oysters and brown shrimp, mainstays of the local fishing industry, out of their current ranges. Federal scientists feared that the salinity drop could cause skin diseases in the bay’s dolphins, killing maybe a third of them. Opponents noted that even if it completes everything in the plan, the state will still lose more wetlands – 2,300 square miles — than it saves or creates – 1,200 square miles.

The scheme went on life support the day voters sent Jeff Landry to the governor’s mansion in 2023. He had been a staunch opponent of the project as attorney general, questioning its ballooning cost — $3.1 billion — and claiming it would kill fisheries important to Cajun culture. A month after our visit, Landry canceled the project.

Its demise didn’t likely lessen Charamie’s resolve “People ask why do I live here?” she said before we said our goodbyes back at the dock. “Where am I to go? This is home.”

It would be a sentiment we would hear again and again.

Next: Life on the edge.