COLUMBIA — In a land where fire and water dominate and bountiful natural landscapes have a history of unnatural manipulation, a recently released water management plan for Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge is seeking to restore and protect a unique environment in North Carolina’s vast coastal plain that is at the frontlines of a rapidly changing climate.

“This place is really, really a special place,” Wendy Stanton, the refuge’s manager, told Coastal Review. “We’re all facing these climate change, sea level rise issues on this peninsula. It’s a very vulnerable area.”

Supporter Spotlight

The refuge’s water management plan and environmental assessment released Aug. 8 is intended as a dynamic working document to serve as a guide for the next 15 years. In Pocosin Lakes, which is crisscrossed with drainage ditches on flat land barely above sea level, where water comes only from the sky — sometimes in deluges, sometimes barely at all — and where desiccated peatlands had become fuel for fires, water management is a conservation balancing act upon which the entire ecosystem depends.

Ongoing success with rewetting pocosin shows hope that restoration is a critical component of management that produces results, with recent wildfires controlled before they were able to spread like previous fires that had burned deep into the peat. As had become evident, pumping water from the canals won’t decrease flooding, but it could increase fire hazard.

“By draining the peat we’re increasing the risk for catastrophic ground fire,” Stanton said. “You know, we’ve had so many fires over the years since the ’80s, before it was even refuge land. We’ve learned a lot of lessons from those fires. So we just we just can’t do that.”

Healthy peat soils in restored areas hold moisture longer than peat soils in an open drainage system, and saturating the soil inhibits intense ground fires in peat, according to the plan. At the same time, the surface vegetation is allowed to burn, which is good for peat ecosystems.

As scientists urgently seek ways to mitigate climate change, the refuge’s peat soil also has gained much attention for its ability to hold tons of carbon, the main pollutant causing global warming. But when dried-out pocosin burns, it releases that stored carbon into the atmosphere.

Supporter Spotlight

Established in 1990, Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge was named for the spongy peatlands known as pocosin — an Algonquian word meaning “swamp on a hill” — that make up much of the region’s soil. Although dominated by the shrubby vegetation of pocosin habitat, the refuge also contains hardwood forests, Atlantic white cedar, farmlands, lakes, ponds, bird impoundments and cypress gum swamp, according to its website.

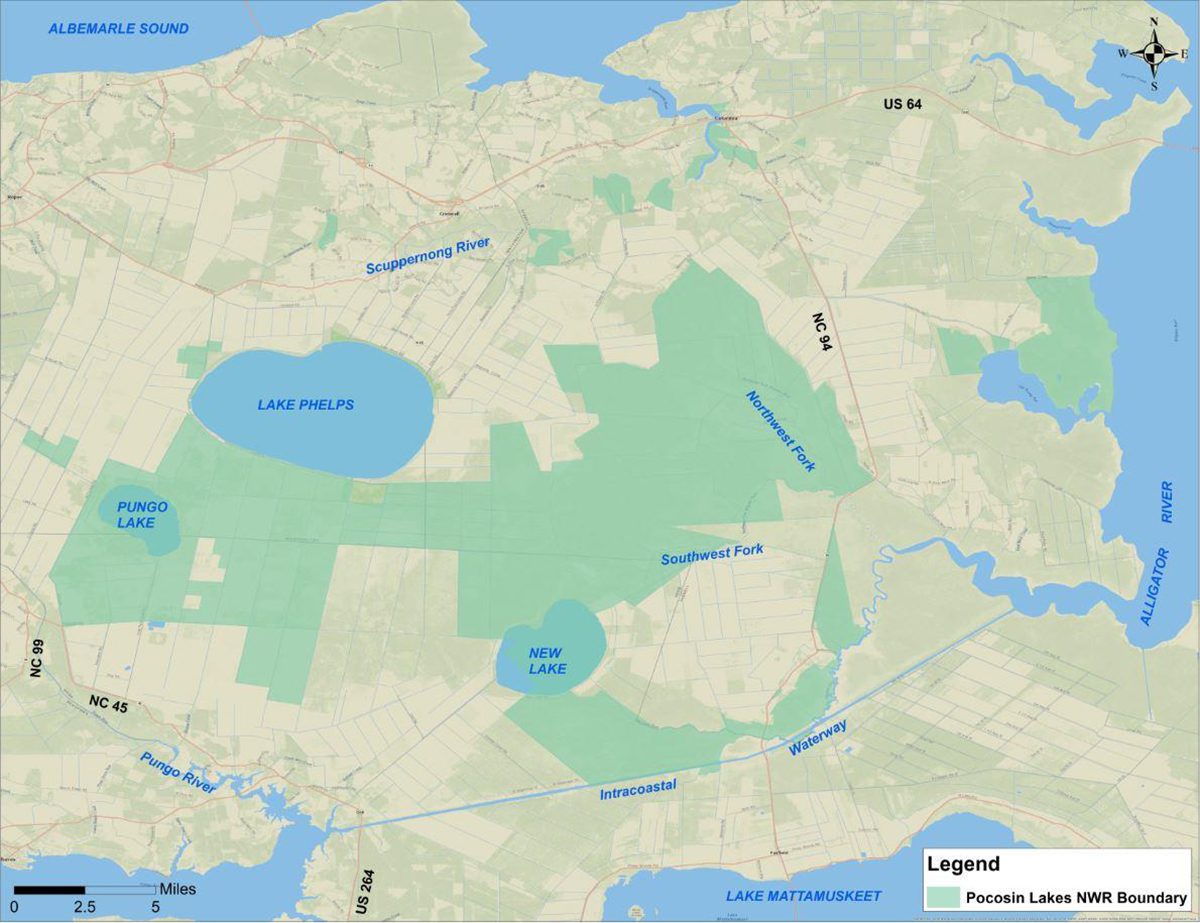

The refuge is situated within the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula, the second largest estuarine system in the continental U.S. Spanning Washington, Hyde and Tyrrell counties, the 110,106-acre refuge hosts huge numbers, about 100,000 a year, of migrating and resident waterfowl, most notably tundra swans that arrive by the thousands every November.

Wintering snow geese also visit every year, as well as numerous duck species. Managed waterfowl habitat encompasses about 8,300 acres within the refuge, including Pungo Lake and part of New Lake.

“And wintertime is a real special time to come to the Pungo unit because we have these absolutely spectacular fly-outs of waterfowl from Pungo Lake,” Stanton said.

Numerous other neotropical migratory and land birds also stop over or breed at the refuge. And the endangered eastern red wolf and red-cockaded woodpecker, both listed as protected under the Endangered Species Act, use the refuge as habitat. The diverse wildlife populations also include white-tailed deer, black bear, reptiles, amphibians and fish.

Land is only 20 feet to a few feet above sea level, and the flood-prone region has lost population since the early 20th century. Hunting, fishing, forestry and farming are major sources of employment, with ecotourism a new source of income, but the counties remain some of the poorest in the state.

With such a complex ecosystem, Pocosin Lakes’ water plan is by necessity flexible and adaptable, Stanton said.

Funding has been provided through the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which awarded $27.25 million, about $5 million of which is going toward nature-based solutions to support the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission game lands. Another portion will be used to maintain the more than 37,000 acres of restored coastal wetlands, which make up 86% of the highly altered peatlands.

The remainder of the money, she said, will be used for Pocosin Lakes to complete the infrastructure for a second restoration area between Evans Road and Harvester Road, southeast of Lake Phelps, which is currently only partially restored.

Some areas of the refuge will raise water levels using a system of gates, pumps and culverts in canals, Stanton explained. But in other areas, water levels will be decreased, or nature will be allowed to take its course with sea level rise.

Four U.S. Geological Survey continuous groundwater monitoring wells help provide a glimpse of what is going on below the surface, which is helpful during the fire season, she said. In addition, the refuge is testing improved water level monitoring equipment — a task now done by hand.

“We have people go out there and they just use a yardstick to measure the water levels at the different structures,” Stanton said.

The new water management plan incorporates information from a 1994 hydraulic and hydrologic study that developed strategies to restore the pocosin by raising water levels, a water inventory assessment in 2016 that evaluated long-term water management needs and threats, and management documents for the endangered red wolf and red-cockaded woodpecker, as well as protection guidelines for the bald eagle.

“Fortunately, the artificial drainage level in the extensive drainage/ditch systems can be managed with relatively simple infrastructure, allowing the Service to eliminate excessive artificial drainage of water via the ditches from the refuge’s peat soils,” according to the plan. “This allows rainfall to be captured and held in the peat soils, returning their natural sponge-like qualities. Therefore, while evapotranspiration can cause the water table to drop, peat soils in restored areas will retain moisture longer than peat soils in an open drainage system.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the land was cleared and the existing drainage system was installed by First Colony Farms, according to documents. In small demonstration areas, the upper part of the peat layer was skimmed off to make land preparation easier, although ultimately very little land was actually farmed. Between regulatory restrictions and high costs, peat mining was also not possible.

Eventually the land was sold and then later donated to the federal government.

Today, there’s active farming in the Pungo unit, Stanton said, with about 1,200 acres of cooperative farm lands. The refuge contracts with some local farmers to leave about 20% of standing corn and winter wheat as cover crop.

“That not only helps conserve the farm soil, but it provides winter browse or green browse for the wintering tundra swans,” Stanton said. “The corn provides a ‘hot’ food. It’s actually high in carbohydrates for the wintering waterfowl.”

The refuge has held several meetings with the surrounding community, Stanton said. The sessions focused on smaller areas around the refuge, on what the refuge “is trying to accomplish, and also hear their concerns and how we can work together.”

There was a period in recent years when area farmers angrily blamed Pocosin Lakes’ peat restoration for flooding their land, although refuge officials said that the flooding problem was nearly all due to repeated extreme rainfall, some associated with tropical storms.

During the process of developing the water management plan, the refuge stepped up communication and its outreach to the community, Stanton said.

“I think relationships have improved tremendously,” she said.

Stanton said that a lot of the agricultural lands are family run farms, some for generations, and they’ve been having increasing challenges with drainage because of sea level rise. But if there’s a problem around the refuge that they want to address, Stanton said, she is “happy to go out and meet with them, or we can talk about it and let’s see what we can do.”

Stanton said that the refuge can sometimes help mitigate impacts of heavy rain on crops by manipulating their drainage structures to slow down water flow or hold the extra water until harvesting in done in an area.

In general, water-control structures — flat board risers — hold back or release water that flows in canals to rewet the pocosin, she said. But they also can hold back water produced by storms — up to a point.

“During hurricanes, sometimes we’ll get 20 inches, and nor’easters also can dump a lot of rain,” Stanton said. “We’re getting a lot more rain bombs.”

But the refuge cannot empty the canals in anticipation of a storm, a question she often hears. The idea is that the refuge would then be able to act as retention pond — except it wouldn’t, she said, because there’s only a certain amount of capacity in the canals. The risk is that rather than protecting the farmlands, draining them would either increase the risk of wildfires by exposing the pocosin to drying — they’re very difficult to rewet — or the water will land right on top of the pocosin and sheet flow out.

Vegetation in pocosin is “fire-dependent,” according to refuge documents. With its high organic content, peat burns readily, but the severity of ground fire is related to the water table level. Before people began altering the landscape, pocosin fires were typically contained above ground, refuge officials said. But altered land or peat affected by severe drought, will lose its protective moisture, and peat fires could burn extremely deeply and for a long time.

After starting in 1923, a logging slash fire known as “the Great Conflagration” burned until extinguished in 1926, torching about 150 square miles and smothering nearby communities in yellow peat smoke for entire summers, according to the refuge document.

The first of two catastrophic fires in Pocosin Lakes was ignited on Allen Road by an escaped debris fire during a drought in spring 1985 in the Pungo unit, which was then state land. It burned through 100,000 acres and as deeply as 3 feet, destroying 26 homes before stopping at the banks of the Alligator River. During the eight weeks it burned, an estimated 1 million to 3.8 million metric tons of carbon were emitted into the air.

The second one, the Evans Road wildfire, was started by lightning on nearby private land on June 1, 2008. After burning 40,740 acres at average depths ranging from 6 to 24 inches, the fire was finally extinguished in January 2009. In areas on private land with the driest conditions, the fire smoldered 5 feet deep into the peat. Less was lost in the refuge because of an ongoing hydrology project that was completed in 2010. By the time the Evans Road fire was completely out, an estimated 10 tons of carbon had been emitted.

Two smaller wildfires in the refuge and the nearby area have occurred within the past year, Stanton said. One was in July 2022, followed by another in March.

The March fire, which began on private land by a debris fire spread by wind, became a ground fire. By then, the refuge knew the fire had to be quickly saturated before getting a chance to go deeper.

“You’ve got to flood it,” she said. “We learned that from Allen Road and Evans Road fires.”

In the short term, Stanton said, the refuge is focusing on completion of the infrastructure in the pocosin restoration area. Also, the refuge will continue work with stakeholders and adjacent landowners to help address drainage issues and other concerns they may want to discuss “to understand more about what we’re doing and the values of pocosin wetlands.”

But the changing climate presents challenges for the future. Pocosin Lakes is part of the Atlantic coastal plain that is subject to some of the highest sea level rise on the coast. Plus, the land accretes vertically unlike most wetlands and is not influenced by tides or sediment travel.

The ability of the pocosin coastal wetlands to adjust to rising seas may be limited, according to the plan.

“If the rate of sea level rise exceeds the vertical accumulation rate of peat in these wetlands,” the document said, “extensive areas could be submerged within a relatively short time.”