Submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, also referred to as seagrass, provides critical ecosystem services in coastal waters.

SAV protects against shoreline erosion, improves water quality and provides habitat for fish and waterfowl. It is critically important to the wellbeing of both estuarine ecosystems and coastal communities.

Supporter Spotlight

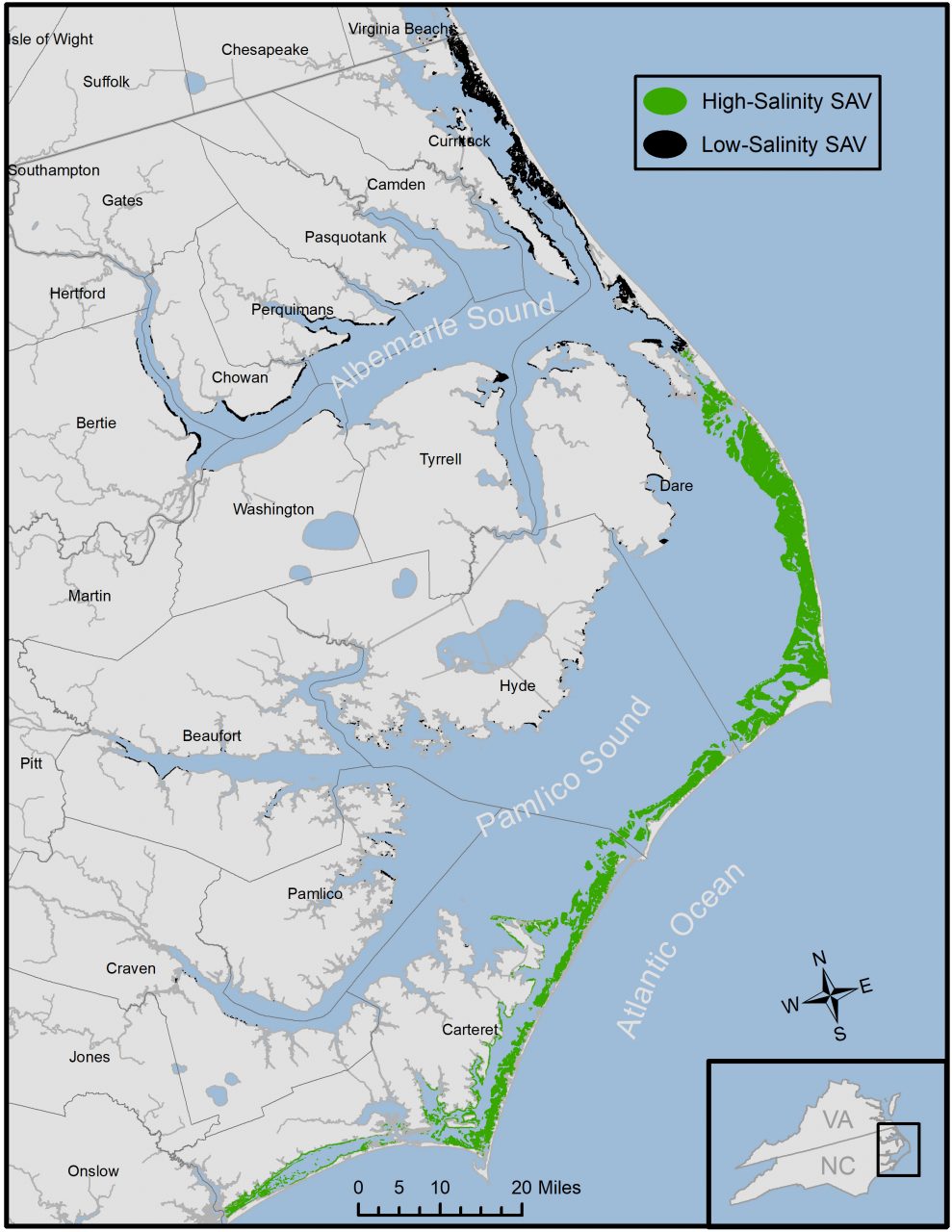

North Carolina is home to the highest seagrass acreage on the Atlantic seaboard. But within the state and around the world, SAV is under threat. Some estimates say that since 1980, the world has lost nearly a third of its total seagrass. The decline has accelerated in recent years due to human activity such as habitat destruction and pollution. The loss in SAV not only presents issues within the ecosystem, but comes with hefty economic costs.

A new report from Duke University and North Carolina State University details the economic losses associated with the decline of SAV in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary. The report was prepared using funding from the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, or APNEP. A conservative estimate from the study projects that losing 5% of submerged aquatic vegetation over the next 10 years could cost the state $8.6 million.

Poor water quality is one of the primary threats to SAV.

“SAV is critical to maintaining good water quality in the estuary,” said Dr. Timothy Ellis, quantitative ecologist for APNEP. “But it also requires good water quality to grow.”

If water is too polluted, sunlight cannot reach the seagrass on the ocean floor. This makes it harder for seagrass to grow. It becomes a destructive cycle, since one of the primary benefits of SAV is that it helps clean the water.

Supporter Spotlight

According to Ellis, this report attempts to translate ecological consequences such as these into economic terms. The hope is that in doing so, more people will be able to understand the significance of SAV declines.

“This is just another piece of the puzzle that we’re trying to put together to help convey the importance of this resource,” Ellis said.

Environmental economist Dr. Sara Sutherland of Duke University was a co-primary investigator for this report. While it is hard to completely monetize ecosystem benefits, she emphasizes the usefulness of economic terms when addressing natural resource issues. It is one of the clearest ways to convey to policymakers and other stakeholders how SAV declines will affect the economy.

“People rely on these ecosystem services without paying directly for them,” Sutherland said. “It’s important that we understand the value of our natural resources.”

Sutherland and the other researchers used transfer benefit methods in order to make their projections. In other words, they didn’t collect their own data, but drew from available studies. From there, they created as comprehensive of a picture as possible regarding the economic cost of SAV loss. They focused on four main categories: commercial fishing, recreational fishing, carbon sequestration and home values.

Using this data, they charted four possible SAV-loss scenarios for the next decade: 5% loss, 15% loss, 25% loss and 50% loss. If SAV in the estuary declines by 5% in the next 10 years, the midpoint estimate for the total cost is $8.6 million in 2019 dollars. If SAV declines by 50%, the cost is projected to be $88.8 million.

Notably, over half of the cost in all scenarios comes from the carbon sequestration category. SAV absorbs carbon dioxide and stores it. The loss of seagrasses would release that carbon back into the world.

But commercial and recreational fishing will also be greatly affected by SAV loss. Blue crabs rely on seagrass as a nursery habitat, and a 5% decadal loss in SAV could result in $700,000 in lost profit for the commercial fishing industry. If there is a 50% loss in SAV, that cost rises to $6.7 million.

The data shows that SAV loss affects many people without them realizing it. Even home values can be affected in the next decade by the loss of seagrass.

“The idea is that when the SAV declines, we lose some of the value that we get from these ecosystem services,” Sutherland said. “And that value is capitalized into the property value for homeowners.”

The researchers focused on a 10-year timeframe because projections for more than 10 years would include too much uncertainty and also because much of North Carolina’s coastal policy is developed using increments of five to 10 years. The actual costs are not limited to the 10-year timeframe of the report — SAV lost today will continue to impact the state’s economy beyond the projected time period.

Both APNEP and Sutherland emphasize that despite the staggering potential costs in each scenario, the projections are extremely conservative. Without more data, it is impossible to get a complete picture of what declines in SAV cost financially.

For example, for the commercial and recreational fishing categories, the researchers only focused on species for which they had data. These were red drum, blue crab and spotted seatrout. But the research team believes that other species for which they don’t have data would also be affected by declines in SAV.

Ellis hopes that this report will encourage other researchers to start filling in those gaps. If the report is to eventually be updated, this initial version serves as a roadmap toward what future research is needed. APNEP hopes to facilitate some of this research in the coming years.

“We have aspirations of updating this economic report down the road, but we want to make sure we put our program and our scientific community partners in a position to be able to produce an updated report that moves the ball forward,” Ellis said.

In addition to inspiring future research, Ellis hopes that this report makes the plight of SAV loss more relatable to a wide audience. It could fuel efforts or legislation to restore and protect SAV.

Seagrass restoration is a costly endeavor, and currently has a two-thirds failure rate. So APNEP is addressing SAV conservation in two ways. First, by focusing on improving water quality so that SAV can thrive. And second, by attempting to preserve the SAV that currently exists in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary. Because if it is lost, this report shows that the effects will be costly.