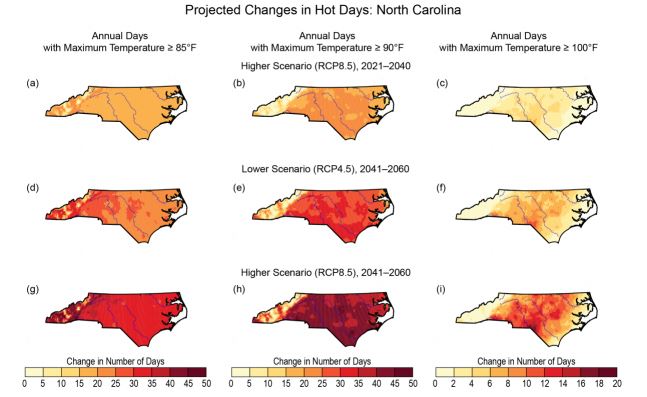

column) for North Carolina for two mid-century time periods and two climate futures. Source: NCICS

North Carolina can expect large changes in climate by the end of the century, much larger than any time in the state’s history, and it’s very likely that temperatures here will increase substantially during all seasons unless the global increase in heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere is stopped.

Temperatures warmer than historic norms, disruptive flooding from rising seas, increasingly intense and frequent rainstorms and more and more intense hurricanes are “virtually certain” in the next 80 years.

Supporter Spotlight

That’s according to an independent, peer-reviewed report released Wednesday by North Carolina State University’s North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies, or NCICS. As a result of hotter temperatures and increased humidity, the state can face public health risks, more frequent and more intense heavy rains from hurricanes and other weather systems, increased flooding in coastal and low-lying areas and severe droughts that are more intense and that will increase the risk of wildfires.

“Increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are most likely causing much, if not all, of the warming that we have observed,” said David R. Easterling, one of the report’s 15 authors, during a press conference Wednesday.

The institute is a multidisciplinary team of experts collaborating in climate and scientific research. The report was assembled, reviewed and revised over the course of eight months beginning in July 2019 and was prepared in response to a request from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality as part of the state’s response to Gov. Roy Cooper’s 2018 Executive Order 80.

While there were no real surprises in the report, which looks at observed and projected climate change in North Carolina and whose findings are consistent with the U.S. National Climate Assessment, it brings the science to the state level and highlights the specific challenges ahead for North Carolina.

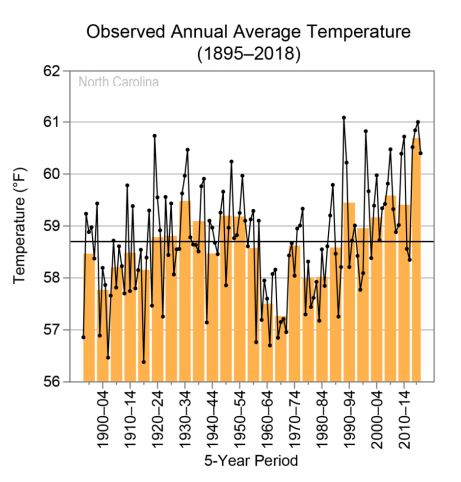

The researchers said 2009-2018 was the warmest 10-year period on record in North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s about a half degree warmer than the warmest decade in the 20th century, the 1930s, the Dust Bowl era,” Easterling said, adding that as the report was being finalized, 2019 turned out to be the warmest year on record for North Carolina and the second warmest globally.

Also, the past four years saw the largest number of heavy precipitation events on record for the state.

So what does it all mean for folks in coastal North Carolina?

The researchers said government officials should take the report into consideration when planning for new infrastructure, such as roads that will have to be designed to different standards to withstand the climactic changes. Individuals can also do their part to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and concentrations.

State Climatologist Kathie Dello, also an author of the report, suggested that North Carolina residents should talk about the report with their friends, families and neighbors.

“There are so many folks who don’t think about climate all day like we do on the panel, and I’ve heard a number of times from folks, ‘This is the first time someone’s talked to me about climate change or projections or what I should expect in my town.’ So, have the conversation. I think it’s really effective and people trust you as a messenger because they know you, they like you and trust you about other things,” Dello said.

“There are so many folks who don’t think about climate all day like we do on the panel, and I’ve heard a number of times from folks, ‘This is the first time someone’s talked to me about climate change or projections or what I should expect in my town.’ So, have the conversation.”

Kathie Dello, State Climatologist

Reide Corbett, director at the Coastal Studies Institute, dean of Integrated Coastal Programs for East Carolina University, and another author of the report, said coastal residents should be thinking about more sustainable growth, not just after disasters such as Hurricane Dorian’s flooding on Ocracoke Island, but also as high-tide, or “sunny day” flooding becomes more and more an everyday occurrence.

“That’s something that, locally, many of the communities need to start thinking about, preparing for and responding to likely after an event,” he said. “I think Ocracoke is a good example where, as they’re rebuilding, they’re considering the storm that they just had and rebuilding to new standards, not rebuilding to what it was in the past.”

Different responses may be necessary along the North Carolina coast, depending on where a community lies.

Sea level is rising 1.8 inches per decade at Duck on the northern Outer Banks, but only at a rate of 0.9 inches per decade at Wilmington on the southern coast because land along the northern coast is settling or subsiding more rapidly.

Also, the southern coast of North Carolina experiences more tropical storms and stronger hurricanes than the northern part of the state does, said Rick Luettich, director of the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City and a report author.

“That trend in and of itself will certainly be sustained,” he said, adding that as global mean sea level rise accelerates, the differences will be increasingly less obvious.

“As sea level rise starts going up faster and faster, that difference will become smaller and smaller,” Luettich said.

While the latest report deals mainly with the science of climate change, a risk assessment and resiliency plan are under review. Subsequent reports will deal with the consequences, such as the effects on agriculture, fisheries and other natural and economic resources and how to address those issues.

The authors agreed that examining the challenges specific to the state is an important step.

“The idea that science is being incorporated into policy in North Carolina is a huge step forward, particularly from a sea level and inundation perspective,” Corbett said. “I’m very pleased with the direction that we’re going and this report is the first step for North Carolina and really using it in developing science-based policy.”