Brunswick County plans to fund essentially half of $99 million in water plant upgrades through a loan program administered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that likely will reduce financing costs by millions of dollars.

EPA announced this month that Brunswick was among 39 applicants nationwide — and the only one in North Carolina — selected to apply for Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act, or WIFIA loans.

Supporter Spotlight

The Brunswick County Board of Commissioners in May approved construction of a low-pressure reverse-osmosis, or RO, plant at its Northwest Water Treatment Plant.

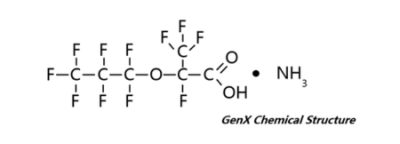

That decision followed a study comparing options to remove GenX and other fluorochemicals in the Cape Fear River, source of the plant’s drinking water.

The contamination came to light in June 2017, following media reports that researchers had discovered GenX and a host of similar substances emanating from the Chemours chemical plant on the Bladen-Cumberland county line near Fayetteville.

Chemours officials said the GenX in the river was a byproduct of a manufacturing process that had been ongoing since about 1980.

GenX and other fluorochemicals elude conventional municipal water treatment, so they also turned up in drinking water sourced from the Cape Fear by Brunswick and other utilities serving more than 200,000 people in southeastern North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

Late last year, under pressure from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, Chemours suspended all discharges to the river, capturing its wastewater from off-site disposal.

The state’s investigation also broadened to encompass Chemours’ air emissions, thought to be responsible for contamination that turned up in hundreds of private wells miles from the plant.

Last month, Chemours broke ground on a $100 million project aimed at reducing those emissions to 1 percent or less of 2016 levels.

‘It Will Greatly Benefit the Ratepayers’

The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act of 2014, or WIKIA, authorizes EPA to provide federal loans or loan guarantees to organizations ranging from corporations and joint ventures to state and municipal governments to fund for drinking and wastewater projects.

A key feature is an interest rate equal to the U.S. Treasury rate at the same maturity: Participants can borrow at the same rate as the federal government. In addition, borrowers can customize repayment schedules, taking as long as 35 years to repay. Brunswick can finance as much as 49 percent of the project cost through the WIKIA program.

“The county is looking for opportunities to finance the project at the lowest possible rate for the benefit of our water customers,” Brunswick County Manager Ann Hardy said in an interview Tuesday.

“We’re not only applying for the WIKIA funding. We’re also seeking state revolving funds and any grants that might be available,” she said. “These federal and state programs that we’re able to possibly use to finance the cost of the RO plant will provide us better financing terms, lower interest rates and a cheaper cost structure than going out into the bond market with a revenue bond.”

The county won’t know its rate until the loan is secured, but Hardy said: “Typically, it’s a savings of a percentage (point) or two, maybe more” compared with a revenue bond. Over the life of the loan, that should result in millions of dollars in savings.

While construction and operating expenses may not change, the decreased financing costs should help the county keep rate increases below what they might be otherwise.

“I think it will greatly benefit the ratepayers,” Hardy said.

‘Robust Technology for Unidentified Contaminants’

Brunswick chose reverse osmosis based on a recommendation from engineering and construction firm CDM Smith, which compared options that also included granular activated carbon and ion-exchange media.

The firm’s recommendation, following a pilot test of a scaled-down RO system, stated that reverse osmosis removed more fluorochemicals more consistently than other options.

It also would be effective at removing most 1,4-dioxane, an industrial chemical used in solvents, paint strippers, greases and waxes that is classified by EPA as “likely to be carcinogenic to humans.” That contaminant has turned up at relatively high levels in Brunswick’s drinking water in tests conducted in recent years.

CDM Smith also wrote that reverse osmosis “is the most robust technology for protecting against unidentified contaminants.”

Construction of the reverse-osmosis upgrades is estimated to cost $99 million. Annual operations and maintenance are expected to run $2.9 million.

The county already had planned to spend $38 million to expand the plant’s capacity and help fund a second line to convey raw river water to the Northwest plant, which serves about 70,000 customers, including those of other utilities.

The second line not only will provide redundancy in case of a break in the current line and capacity to meet anticipated growth, it also is needed because RO typically uses more water than other treatment methods. Depending on the system, as little as 85 out of each 100 gallons of raw water treated would be available for drinking.

Filtering GenX, Then Discharging It

In addition to securing funding, Brunswick also must apply to discharge wastewater under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES, which in North Carolina is administered by DEQ.

That process “began in February and has proceeded with no ‘red flags’ from regulators. Bidding and construction of the project is expected to begin in June of 2019,” the county wrote in its announcement of the expansion.

John Nichols, Brunswick’s public utilities director, said Tuesday the county plans to submit the application in the next few days.

Those discharges likely will include the fluorochemicals such as GenX removed during treatment.

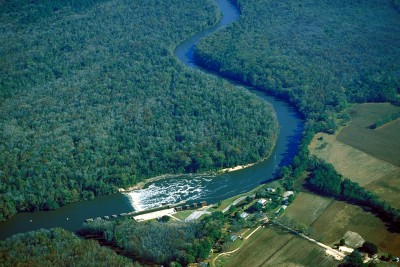

The current NPDES permit for the Northwest plant states it discharges its wastewater to Hood Creek, part of the Cape Fear River basin.

Coincidentally, although no other water utilities are downstream of Brunswick’s discharge, other municipal treatment plants upriver, which receive wastewater from local manufacturers, are thought to be sources of the 1,4-dioxane contaminating Brunswick’s drinking water.

“(The discharge) can only include what’s being taken out of the river,” Hardy said. “You’re taking out at one point and only putting back in what you take out of the river. You’re not adding anything new to the river.

“Our primary concern is that Chemours stop discharging GenX into the river,” she said. “If they stop, then there’s no GenX to put back in.”

Nichols said county staff has met with regulators a number of times regarding its plans, including the discharge.

“We did not get any negative reaction,” he said. “We asked them if they saw any fatal flaws or major issues, and none came up.”

DEQ did not respond to an email with questions regarding the application and the discharge.

Holding the Polluter Responsible

Brunswick isn’t the only water system looking at multi-million-dollar upgrades to deal with Chemours’ contamination. The Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, which provides water to most of New Hanover County’s residents, is moving forward with plans to add granular activated carbon beds to its Sweeney Water Treatment Plant.

CFPUA initially considered RO but set it aside because of concerns about costs, waste-disposal challenges and other considerations.

Sweeney already has ozonation, biofiltration and UV disinfection systems, features found at only a handful of water utilities in North Carolina, and can remove most 1,4-dioxane from water it treats.

For its part, CFPUA has applied to DEQ for a $46.9 million grant to fund its construction.

In addition, Brunswick and CFPUA are suing Chemours for damages they say resulted from the contamination in the Cape Fear River. Each has maintained that, ultimately, Chemours rather than utility customers should pay for whatever measures are needed to remove fluorochemicals from drinking water. Any resolution to those claims, though, likely is years away, longer than officials were willing to wait to address their communities’ drinking water issues.

“First and foremost,” Hardy said, “the county is looking to hold those responsible for placing the chemicals in the river financially responsible. And we’re seeking to recover that through our suit against Chemours.”

Those suits have been combined into a single action. Jim Flechtner, CFPUA executive director, said the utilities are awaiting a ruling on a motion by Chemours to dismiss the suit.

A number of lawsuits claiming damages to area residents also have been consolidated.