First of three parts

CAPE CARTERET – The banks of Deer Creek are a visual testament that seawalls are the preferred defense against shoreline erosion in North Carolina.

Sponsor Spotlight

Like a cookie cutter of many marsh shorelines within the state’s coastal region, the shores of Deer Creek are checkered with bulkheads.

Research shows that these barriers, made from wood, stone or vinyl, slow waves from eating away land, but they can also destroy wetlands and other habitat for marine life.

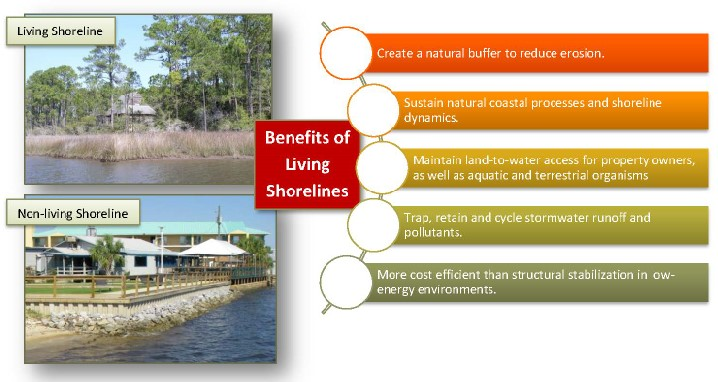

Nationwide, the scales appear to be tipping in support of an alternate, more natural way of controlling inshore erosion. Research is showing that these so-called “living shorelines” are highly effective in protecting waterfront property and better for the environment.

They’re made of organic and structural materials such as bagged oyster shells, wetland plants, sand fill, stone and aquatic vegetation and are generally built in “low-energy” areas where strong currents, high waves and boat wakes aren’t a problem.

Sponsor Spotlight

There is no template for living shorelines. Since each shoreline is different, natural shoreline-stabilization methods must be designed specifically for each site, explained Lexia Weaver, a coastal scientist with the N.C. Coastal Federation.

Since any type of shoreline stabilization changes a shore it means any method will have some effect on habitat.

“There’s definitely not a perfect approach,” Weaver said. “All living shorelines are susceptible to sand buildup, but not all of them will build up fast. With a bulkhead, you’re losing everything in front of the structure.”

Living shorelines come in varying sizes and, depending on the wave action, may require as little as planting marsh grass. Other projects call for a combination of methods, such as installing offshore oyster reefs, rock sills and breakwaters to bear the brunt of waves.

Unlike seawalls, which create a hard barrier between land and water, living shorelines provide a softer form of shoreline protection that still allows water to move.

That’s the case with a stretch of privately owned land in Cape Point, an upscale waterfront development along the banks of Deer Creek in Carteret County.

Here, a series of plastic, netted filled with oyster shells and neatly packed side-by-side in front of the shoreline peek above the water at low tide.

“We put it right up against the shoreline,” Weaver said. “The grass is doing good. There’s fish habitat. There are oysters here.”

The bags create a revetment that breaks wave action before it reaches the shore. Between the bags and a well-manicured lawn is marsh grass that has grown since federation volunteers installed the bags months earler.

The project stretches across about 200 feet of shoreline along two different properties. It took volunteers less than a week to fill the bags and place them in the water.

The project cost, which includes the $200 general permit fee and the price of the bags and the oyster shells they’re stuffed with, was an estimated $1,000, substantially less than a bulkhead, which costs an average of $450 a yard.

Living vs. Hardened

The Deer Creek project is one of dozens the federation has overseen and installed up and down the coast.

“All the ones that we’ve done, they’re working,” Weaver said.

In a state where there is no lack of seriously eroding shorelines, the federation is keen on installing, researching the effectiveness of and educating everyone from contractors to private property owners about living shorelines.

“What we’re trying to do is preserve and protect that really critical line between uplands and estuaries,” said coastal scientist Tracy Skrabal, a federation scientist. “We are losing coastal marsh and we are losing wetlands throughout our coastal system. That is because we’re hardening so many of our shorelines.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that nearly a third of the nation’s contiguous estuarine shoreline will be hardened by 2100 if the structures continue to be built at the current rate and the coastal population continues to grow.

A study published last August by one team of academic researchers estimates that more than 14,000 miles – 14 percent of continental U.S. coastline — has been armored with hardened structures. That’s a conservative estimate, according to the study.

As of 2013, 125 living shorelines had been installed along North Carolina’s marsh shorelines, according to information from the N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve. In comparison, more than 9,900 bulkheads were built.

Rachel Gittman, a postdoctoral research associate at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center in Boston, is a member of the research team that calculated the amount of coastline with hardened structures along the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf of Mexico.

Their research estimates that about 9 percent of both the Atlantic and Pacific’s open coasts shoreline have been hardened. Sixteen percent of shorelines along the Gulf of Mexico are armored.

“Without substantial changes to coastal management policies and development practices, the U.S. coastlines will likely lose their natural defenses,” according to the paper.

Hardened structures may protect against erosion, but ironically, they also cause elevated rates of erosion on the shoreward side of the structure.

These structures wall off estuaries crucial for fish larvae, which seek refuge in shallow water to survive through their juvenile stage.

When a bulkhead or other hardened structure is installed it increases wave reflection, which can push sand in front of the structure, wiping out shallow water habitat.

“Environmentally [living shorelines] are preferable over a seawall or bulkhead,” Gittman said. “They’re maintaining the habitat that marine organisms depend upon and in many cases restoring some habitat that is being used by marine organisms.”

As a doctoral student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Gittman conducted a multi-year study sampling sites where bulkheads and living shorelines were built. The study examined sites before and after the installation of living shorelines.

“We were able to essentially show that fish utilized these constructed living shorelines more than bulkheads,” Gittman said. “There were more fish and more species of fish using those restored shorelines.”

Living shorelines where there is planting and, ideally, oyster restoration, enhance fish habitat locally, she said.

They also are likely to play a vital role in protecting waterfront properties as sea levels rise.

Because they are “living,” natural shorelines can grow, allowing them to keep up with sea-level rise. Research conducted by NOAA shows that living shorelines are growing upward anywhere from two to four millimeters each year, about the current local rate of sea-level rise.

Bucking the Trend

Despite the research, North Carolina waterfront property owners continue to choose hardened structures, particularly bulkheads, over living shorelines.

Each year only a handful of living shoreline permits are filed with the N.C. Division of Coastal Management.

“People are used to seeing bulkheads,” Weaver said. “It’s what they’re used to building.”

And, though they’ve been around for decades in the U.S., living shorelines remain the underdogs of stabilization alternatives because much of the general public simply does not know much, if anything, about them. There’s also a shortage of contractors with the knowledge and training to build these natural structures.

Agencies at varying governmental levels – from NOAA to state environmental regulatory offices and municipalities to nonprofit organizations like the federation – are taking steps to educate property owners and offer training opportunities to contractors.

Perhaps the largest factor hampering an increased demand for living shorelines is the permitting process.

It can take months for applicants to receive approval to build a living shoreline. The process to get a permit to build a bulkhead in North Carolina is much quicker. Most are issued within a matter of days.

North Carolina has a general permit for living shorelines, but most applicants apply for a Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit.

General permit applicants have to go through the Division of Coastal Management whereby applicants are reviewed by the state Division of Water Resources and N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries. After those agencies review an application, the applicant must then go to the Army Corps of Engineers for authorization.

If an applicant directly applies for a CAMA major permit, the state sends the request directly to the corps. This permitting process takes at least 45 days.

State regulators say living shorelines projects are scrutinized because they are usually located in navigable waters and, because they span out into the water, could affect navigation. Natural stabilization projects may also affect essential fish habitat, areas of which are protected under federal law.

Coastal scientists and researchers agree that bulkhead permits should receive the same critical examination.

“Every shoreline needs to be evaluated with regard to its existing functions and values,” Skrabal said. “I think it’s very unfortunate and damaging that bulkheads are not given the same amount of evaluation in terms of their impacts. Property owners by and large are very accepting of living shorelines. That’s never been a problem for us. People like how they look. They like how they function. If it takes three months to get a permit for a living shoreline, but only two days to get a permit for a bulkhead, they’re not going to choose a living shoreline.”

The federation and other environmental groups now wait for what may be a change at the national permitting level.

“We’ve come a very long way,” Skrabal said. “We’re not there nationally yet.”

Learn More

Related Content

Tuesday: What they cost, how well they work