Tidal flooding is creating a potential public health hazard on the streets and roads of coastal towns, according to a recently published study.

The study found elevated levels of fecal bacteria in water samples collected over the course of two months from a tidal creek in Beaufort and its streets following rainfall.

Supporter Spotlight

Dr. Natalie Nelson, an associate professor at North Carolina State University, explained that the study reaffirmed what researchers already knew — stormwater runoff is the largest culprit of elevated levels, or levels that exceed regulatory recreational water quality standards, of enterococcus bacteria in Taylors Creek.

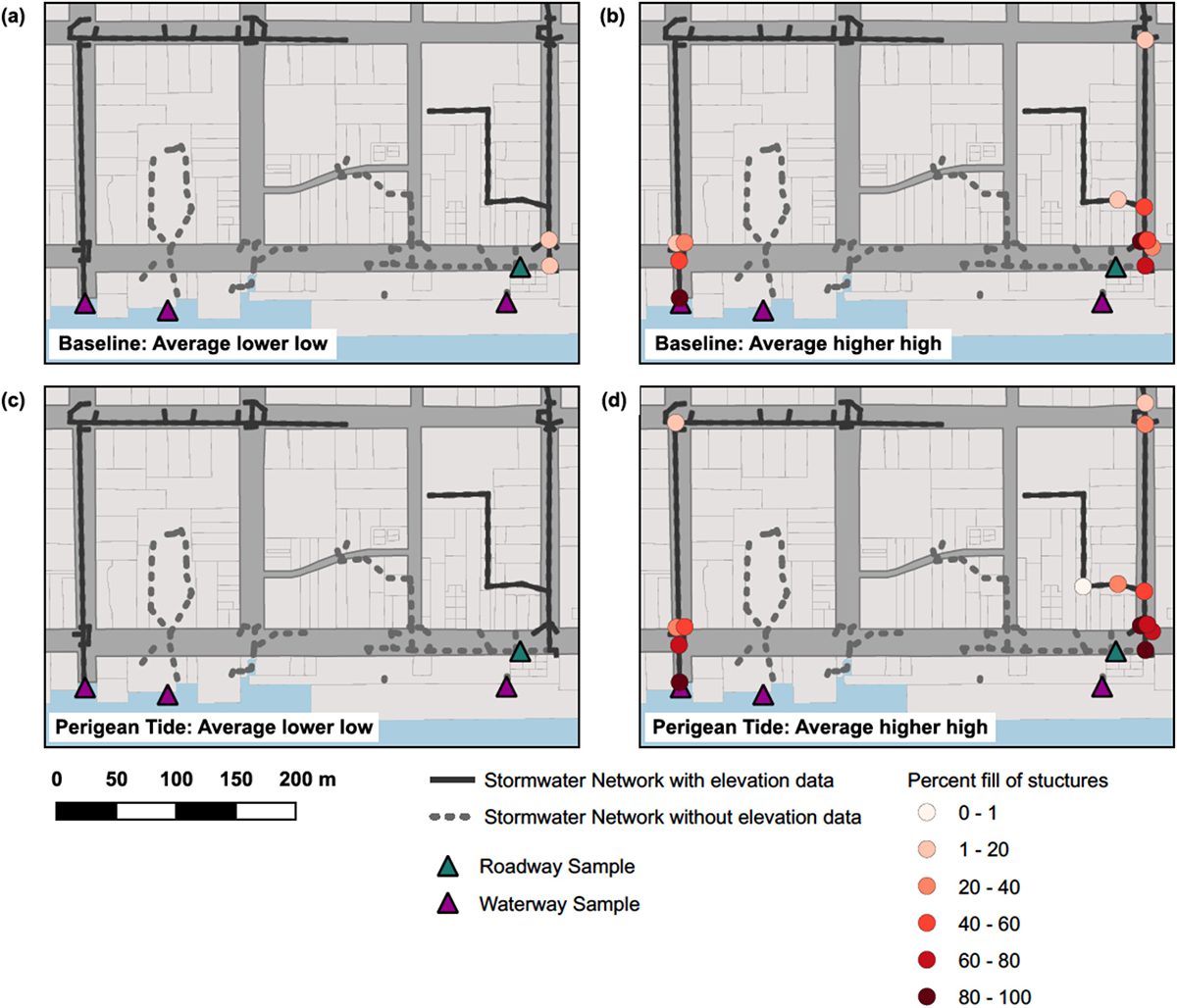

Tidal flooding forces water into the town’s stormwater system that empties into Taylors Creek. When the system exceeds capacity, water overspills onto road surfaces.

This type of flooding occurs when rainfall causes saltwater to overflow from the ocean, sounds and estuaries and, because of sea level rise, it’s becoming more prominent in coastal areas like Beaufort.

Samples collected from floodwater patches on roadways almost consistently had elevated concentrations of enterococcus bacteria.

And, in some cases, bacteria in those samples maxed out the detection limit, Nelson said.

Supporter Spotlight

“What it indicates to us is that the concentrations were likely high because of a source from within the stormwater network,” she said. “We say that because the floodwaters, it’s not like they were so extensive that we could really argue that they might be flushing the land surface. But, because those floodwater patches were pretty small, we think the elevated concentrations were coming from within the stormwater network.”

When floodwaters glazing the roadways drained back into the stormwater system during ebb tide, researchers recorded higher levels of bacteria in the creek, indicating that the contamination in the creek is coming from the stormwater network, Nelson said.

The contamination wasn’t present in all of the locations sampled and the presence of the contamination was brief, she said.

Enterococci are bacteria that live in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and warm-blooded animals. People who swim or play in waters with bacteria levels higher than state and federal standards have an increased risk of developing gastrointestinal illness or skin infections.

“I think the problem that we uncovered is not at all unique to Beaufort,” Nelson said. “The stormwater network was never designed to have water come back up through it and then go into places where pedestrians encounter and so we’re now in an era where we have to think about how our infrastructure systems are being stressed in new ways and how that might lead to new types of issues like maybe floodwaters having issues with contamination, but it’s a topic of ongoing research.”

In recent years, Beaufort has repaved hundreds of feet of one downtown street with pervious pavement, which allows water to soak through to the ground rather than route the water to the town’s stormwater system.

That project fell under the 2017 Beaufort Watershed Restoration Plan, one that aims to restore hydrology and reduce polluted runoff using retrofits that direct stormwater to filtrate into the ground or collect it for later use.

The town is among a number of coastal communities that have been examining how to best respond to what researchers often call “sunny day flooding” and other weather-related issues that are being exacerbated by the changing climate.

Dozens of coastal municipalities and counties have received grants through the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management’s N.C. Resilient Coastal Communities Program, or NC-RCCP.

The program is a creation of the state’s 2020 Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan, which was the result of Executive Order 80 signed by Gov. Roy Cooper in October 2018.

NC-RCCP aims to boost resilience efforts in the state’s 20 coastal counties and encourages those who live and work along the coast to participate in finding solutions to prioritize projects designed to help their communities bounce back from storms and floods.

For more information about tidal flooding and precautions, visit North Carolina Sea Grant’s website.