Reprinted from North Carolina Health News

Though the holiday season is here — with all the responsibilities it entails — some North Carolinians might consider adding one more thing to their to-do lists: weighing in on an EPA proposal that could reshape how the government collects information about per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. The agency is taking input during the public comment period, which is open now and closes on Dec. 29.

Supporter Spotlight

On Nov. 10, the EPA announced a proposal to loosen reporting requirements for businesses that make or use PFAS. Agency officials say the changes are intended to make the rules easier for companies to follow and to avoid duplicate or unnecessary paperwork, while still allowing EPA to collect key information about how PFAS are used and what risks they may pose.

Currently PFAS are regulated under the Toxic Substances Control Act, a federal law that allows the EPA to require businesses to report, test, track or even ban chemicals that may threaten human health or the environment.

In October 2023, the Biden administration’s EPA finalized a one-time PFAS reporting rule under TSCA’s Section 8. The rule requires companies that manufactured or imported PFAS between 2011 and 2022 to disclose how the chemicals were used and provide available environmental or health data. Industry groups have pushed back, saying the rule is too costly and difficult for small businesses to navigate.

“This Biden-era rule would have imposed crushing regulatory burdens and nearly $1 billion in implementation costs on American businesses,” EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin said when announcing the proposed changes. “Today’s proposal is grounded in common sense and the law, allowing us to collect the information we need to help combat PFAS contamination without placing ridiculous requirements on manufacturers, especially the small businesses that drive our country’s economy.”

But environmental advocates and clean water managers say the proposal would significantly weaken PFAS oversight.

Supporter Spotlight

“By EPA’s own estimate, the proposed rule would eliminate more than 97 percent of the information that would have otherwise been generated by the (current) rule,” said Stephanie Schweickert, NC Conservation Network’s director of Environmental Health Campaigns.

“With PFAS and Chemours in North Carolina, we really need more information about PFAS, not less. This (proposal) is very problematic for public health in North Carolina,” Schweickert said.

Harder-to-detect PFAS raise new concerns

The proposal comes when North Carolina researchers are uncovering PFAS pollution that standard monitoring can’t detect — raising new questions about whether EPA already has blind spots.

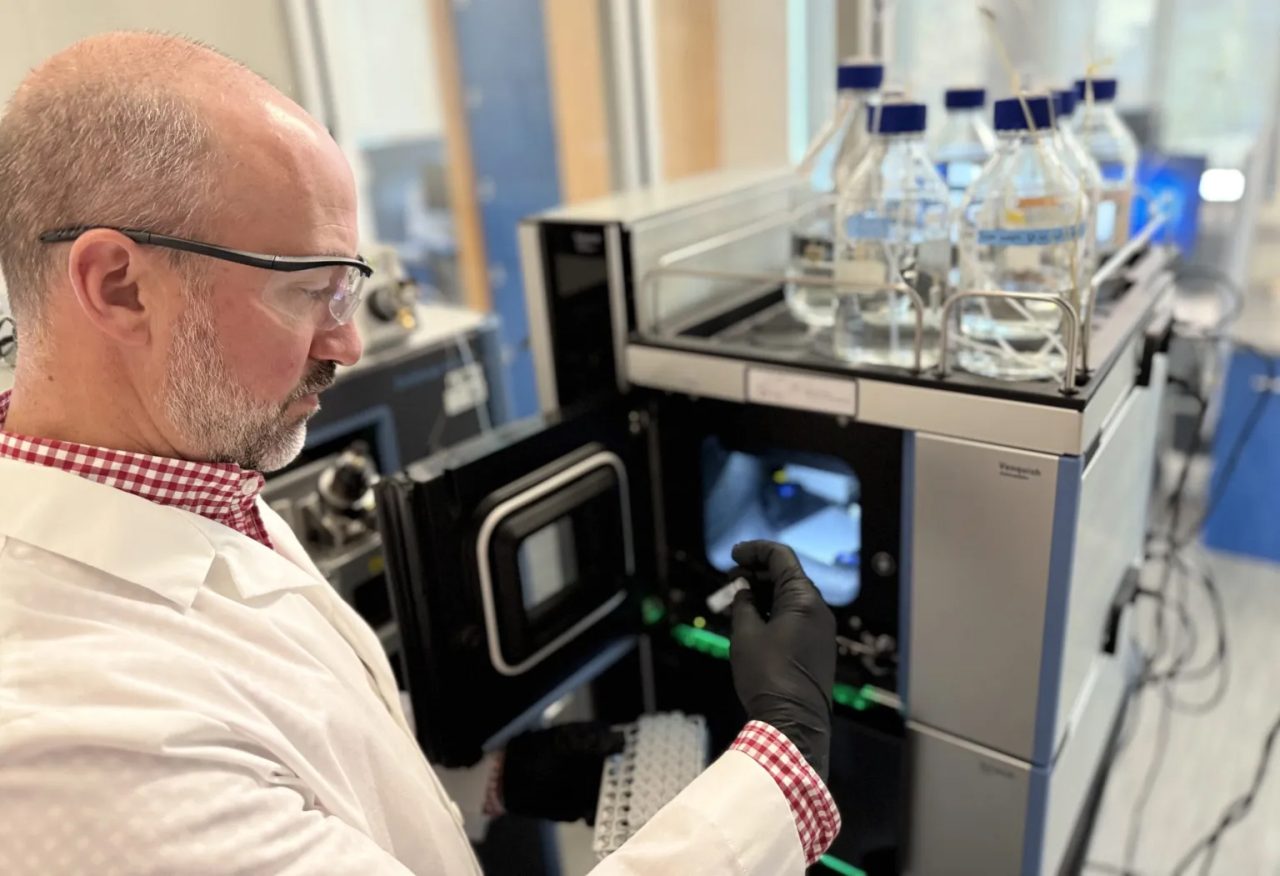

Recent Duke University research uncovered a previously unrecognized source of contamination in the Haw River, a tributary of the Cape Fear River: tiny solid PFAS “precursor” particles in industrial wastewater from a Burlington textile manufacturer that entered the local sewer system. These nanoparticles don’t show up in standard PFAS tests, which typically look for dissolved chemicals. But during wastewater treatment processes, the particles break down into better-known PFAS compounds that can contaminate rivers, drinking water sources and agricultural sludge.

At peak discharge, researchers detected precursor-particle levels exceeding 12 million parts per trillion — millions of times higher than EPA’s enforceable drinking-water limits of 4-10 ppt for regulated PFAS. The findings highlight major blind spots in current monitoring and suggest that industries may be releasing far more PFAS (or PFAS precursors) than regulators currently can detect.

“We have some of the most sophisticated instruments in the world for PFAS analysis, and we couldn’t detect these until we dramatically changed our approach,” said lead researcher Lee Ferguson, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Duke, in a release. “Sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know, and there is a lesson to be learned about blind spots in our analyses when it comes to looking for new PFAS in the environment.”

In a follow-up email, Ferguson said the findings show why PFAS disclosure rules should be strengthened, not rolled back. “Our work highlights why it is important to increase, not decrease, PFAS waste discharge reporting requirements for industries.”

Downstream utilities feel the impact

A public utility that relies on the Cape Fear River, echoed Ferguson’s concerns.

The Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, which provides drinking water to more than 200,000 customers in New Hanover County and spent $43 million installing a granular activated carbon filtration system in 2022 to remove PFAS, said weakened reporting would make their job harder.

“We are concerned that these (proposed) exemptions could create additional uncertainty for utilities, such as CFPUA, that are located downstream from known PFAS polluters,” the agency said.

“Utilities rely upon detailed, accurate data from potential and known contamination sources to inform our treatment processes in order to protect the drinking water we provide our customers,” the statement continued. “Rolling back reporting requirements for PFAS manufacturers passes more of the burden of monitoring and testing source water on to utilities and our ratepayers.”

Advocates say the stakes extend beyond utilities.

“The EPA is carving out loopholes under the Toxic Substances Control Act that allow industry to avoid reporting its use of PFAS — current forever chemicals that pose serious risks to people’s health,” a Southern Environmental Law Center spokesperson said in an emailed statement to NC Health News.

“These exemptions include PFAS produced as byproducts, the very issue at the heart of the Chemours crisis,” the SELC statement said. “For decades, Chemours discharged GenX as a byproduct before intentionally manufacturing it, yet the harm caused by byproduct PFAS is no different from that caused by intentionally produced PFAS. This reality devastated 500,000 North Carolinians who drank—and continue to drink—water contaminated by Chemours’ PFAS pollution, and it remains true for communities across the country today.”

Health risks tied to PFAS exposure

These gaps in monitoring matter because PFAS exposure has been associated with a growing list of health concerns. Often called “forever chemicals” because they break down slowly and accumulate in the body over time, PFAS have been linked to immune system suppression, developmental and reproductive harm, thyroid disruption, elevated cholesterol and certain cancers.

In North Carolina, the GenX Exposure Study has documented elevated PFAS levels in blood samples from people living near the Cape Fear River, along with health markers such as increased cholesterol and changes in liver enzymes that have been associated with PFAS exposure. Researchers say the findings underscore the risks for communities living downstream of industrial PFAS sources.

“Some PFAS are formed as byproducts of chemical manufacturing. These chemicals, even though they aren’t used to make new products, are released into air and water and have been found in the blood of people who rely on downstream drinking water,” said N.C. State University epidemiologist Jane Hoppin, when responding to questions about the new Duke research and the EPA’s proposal.

“In our research, PFMOAA was detected at the highest levels in blood samples collected more than a year before the contamination was publicly identified,” she said. “Other byproducts of PFAS — Nafion byproduct 2 and PFO5DoA — were found in nearly all Wilmington residents tested in 2017 and remain in people’s blood today. We need more, not less, information about chemical byproducts to ensure drinking water safety.”

“The mission of the EPA, in the beginning, was to protect the public and the environment,” said Robert Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University who’s widely regarded as the father of the environmental justice movement. “Anytime you’re relaxing rules that would not only threaten the environment but also compromise public health — that’s the wrong way to go.”

The public comment period is open through Dec. 29. To submit a comment, go to: https://www.regulations.gov/commenton/EPA-HQ-OPPT-2020-0549-0311.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.