New Hanover County beaches could again mine sand from nearby inlets to nourish their oceanfront shores under a proposed law recently passed by the U.S. House of Representatives.

The bill would exempt a handful of federal coastal storm risk management projects on the East Coast from a rule that prohibits local governments from tapping sand sources they have historically used within the Coastal Barrier Resources System.

Sponsor Spotlight

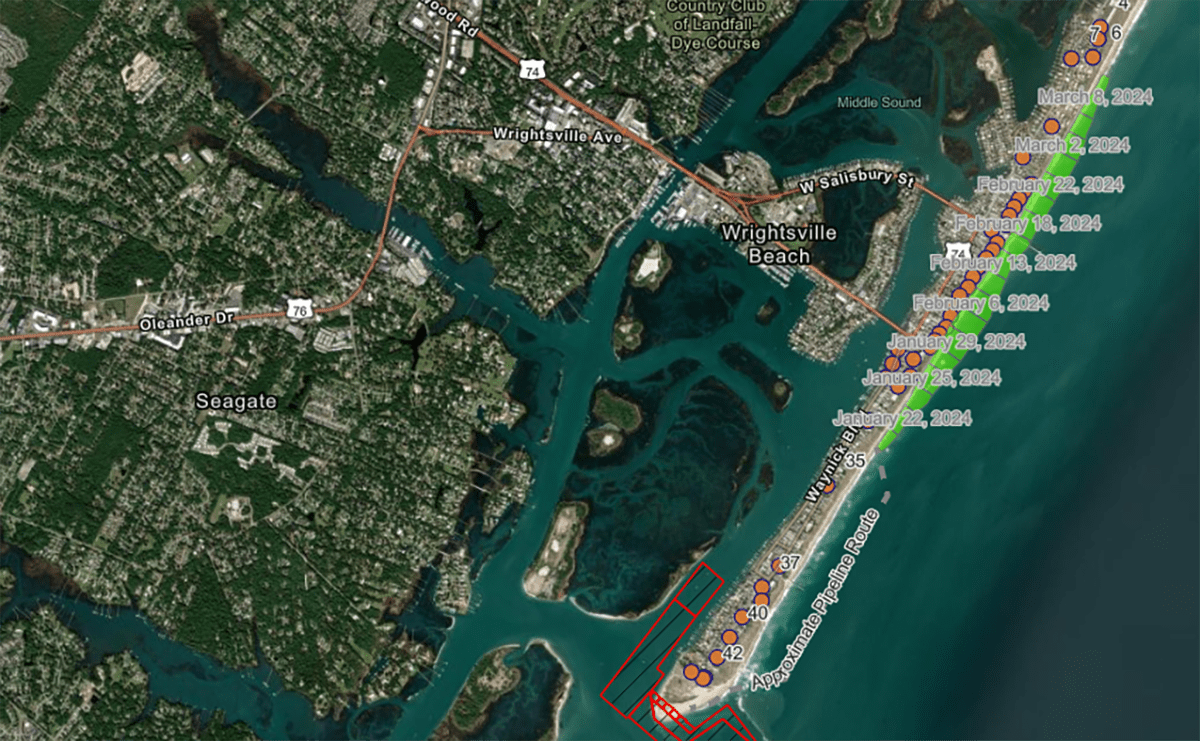

The proposed law would apply only to projects that have been pumping sand from borrow sources within the federally protected system for more than 15 years. Those include Masonboro Island at Wrightsville Beach, Carolina Beach Inlet at Carolina Beach, an inlet in South Carolina and one in New Jersey.

H.R. 524, introduced by Rep. David Rouzer, R-N.C., in January 2023, would also return the use of federal funds for projects that use sand within a Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA, unit to nourish adjacent beaches outside of the system.

“This legislation allows these beaches to continue to use their historic borrow sites for protection from storm damage, maintain their natural ecosystems, and protect our local economy,” Rouzer stated in a press release following the House’s April 11 passage of the bill.

The bill is now with the Senate environment and public works committee.

Sponsor Spotlight

Proponents of the bill argue that allowing projects that had for years used sand within the system to nourish nearby beaches reduces costs and ecological impacts.

“It’s an opportunity to recycle sand. It’s an opportunity to reduce potential environmental impacts. And, it’s an opportunity to reduce federal and local expenditures,” said New Hanover County Shore Protection Coordinator Layton Bedsole. “I think Wilmington had been in compliance 20 years before CBRA was written and we haven’t encouraged development in sensitive coastal locations like inlet shoulders. That’s a major tenant in CBRA.”

Congress passed CBRA, pronounced “cobra,” in 1982 to discourage building on relatively undeveloped, storm-prone barrier islands by cutting off federal funding and financial assistance, including federal flood insurance. The act was also established to minimize damage to fish, wildlife and other resources associated with coastal barrier islands.

Last May, Matthew Strickler, deputy assistant secretary for the Interior Department’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife and Parks, expressed the current administration’s objections to H.R. 524 in his testimony before the House natural resources committee.

Using federal funds to move sand dredged within the system to an area outside of it “is considered counter to CBRA’s purposes,” he said referring to the Coastal Barrier Resource System, or CBRS.

“While some of the sand taken from CBRS units for beach renourishment activities may return to the unit over time, the overall impacts of dredging in these areas protected by CBRA are detrimental to coastal species and their habitats,” Strickler said.

But proponents of the bill argue that years of monitoring these inlets prove otherwise.

“We’re in a situation where Mother Nature brings sand down our beach into an engineered borrow site and then we recycle it back up on the beach in the next three or four years. That’s ideal. We’re recycling rather than mining. We’ve got consistency that works for us that we can work with,” Bedsole said.

December 2023: Sand nourishment to begin in Wrightsville Beach

Wrightsville Beach was using the rich, beach-quality sand routinely pumped from Banks Channel and placing that material on its ocean shore for roughly two decades before CBRA was enacted.

In the mid-1990s, the Army Corps of Engineers permanently allowed the town to use Masonboro Inlet as a sand borrow source, shielding the town from ongoing debates over the interpretation of the law as it pertains to whether sand within a CBRS unit may be dredged and placed onto a beach outside of a CBRA zone.

By 2019, then-Interior Secretary David Bernhardt determined that federal funds could be used to pay for dredging sand with CBRS units and placing that sand on beaches outside of those zones for shoreline-stabilization projects.

A year later, the National Audubon Society challenged Bernhardt’s interpretation in a lawsuit filed against the former secretary, the interior department and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The organization argued the interpretation “vastly expands potential sand mining projects” within areas protected in the system.

The Biden administration overturned the rule in 2021 and Audubon agreed to drop its lawsuit.

The new interpretation forced beach towns that had historically used sand from CBRA zones to look offshore.

Facing exponentially higher costs and an offshore borrow site scattered with old tires broken free from an artificial reef, the town was given an emergency exception by the Corps to get sand from the inlet. That project, which pumped roughly 1.04 million cubic yards of sand onto Wrightsville’s beach, wrapped in mid-March.

The cost to use sand dredged from the inlets is substantially lower than pumping sand from an offshore borrow site.

The last time Carolina Beach tapped the inlet borrow site for sand to place on its ocean shoreline the bid tab was $5 a yard.

“The current project came from the offshore borrow area, as it has, was $11 and some change a yard,” Bedsole said. “It just costs more to go offshore.”

Bids are expected to go out this spring for Carolina and Kure beaches’ nourishment projects, which as of now will use sand from an offshore borrow site.

How that sand might affect the channel Carolina Beach used for years as a sand source has raised concerns among beach town officials.

“We have pulled sand out of that inlet for pretty much my entire life,” said Carolina Beach Mayor Lynn Barbee. “We know what the environmental impacts are. They’re very minimal. We haven’t seen any sort of erosion because of taking that out of there. We haven’t seen any impacts to wildlife, ever, so it’s hard to see what the harm is. What we’ve been doing in the inlet is the borrow pit fills up and we pump that sand out every three years onto the beach and then it drifts back in and fills up and we pump it back out. That seems intuitively better than going out offshore and basically running a sand mine underwater and disturbing what was natural out there.”

Another issue, he said, is how sand pumped onto the beach from the offshore site may affect the inlet, one heavily used by boaters and offers the fastest route for first responders to get into the water.

Barbee said the town has seen “unprecedented” shoaling in Carolina Beach Inlet since it began using the offshore borrow site.

“We have really struggled to keep that open,” he said. “We’ve seen the cost to keep the inlet open go up. If in fact our theory is correct, where else would that sand have come from if it wasn’t introduced from the offshore borrow pit. You’re introducing a new sand source into the traditional system. Certainly, anecdotally, we didn’t have this problem, we do something different, now we do have the problem. It doesn’t seem like it’s a huge leap.”

Barbee said the hope is that the bill will become law before the next project begins.

“If not, we have three more years of these elevated costs, and then we’re just putting more and more sand in the system, and the worry is that when does it become too much?” he said.