A bill that significantly scales back wetland protections is now on Gov. Roy Cooper’s desk.

The 2023 Farm Act restricts state regulation of wetlands to those classified as waters of the United States, often called WOTUS, and a Clean Water Act definition that the U.S. Supreme Court narrowed in May to include only wetlands that have “continuous surface connection” to other water bodies.

Supporter Spotlight

The measure was ratified Monday and sent to the governor Tuesday.

The bill removes the state’s regulatory authority that now protects federally nonjurisdictional wetlands. Advocates and scientists say these isolated wetlands serve important hydrological and ecological functions.

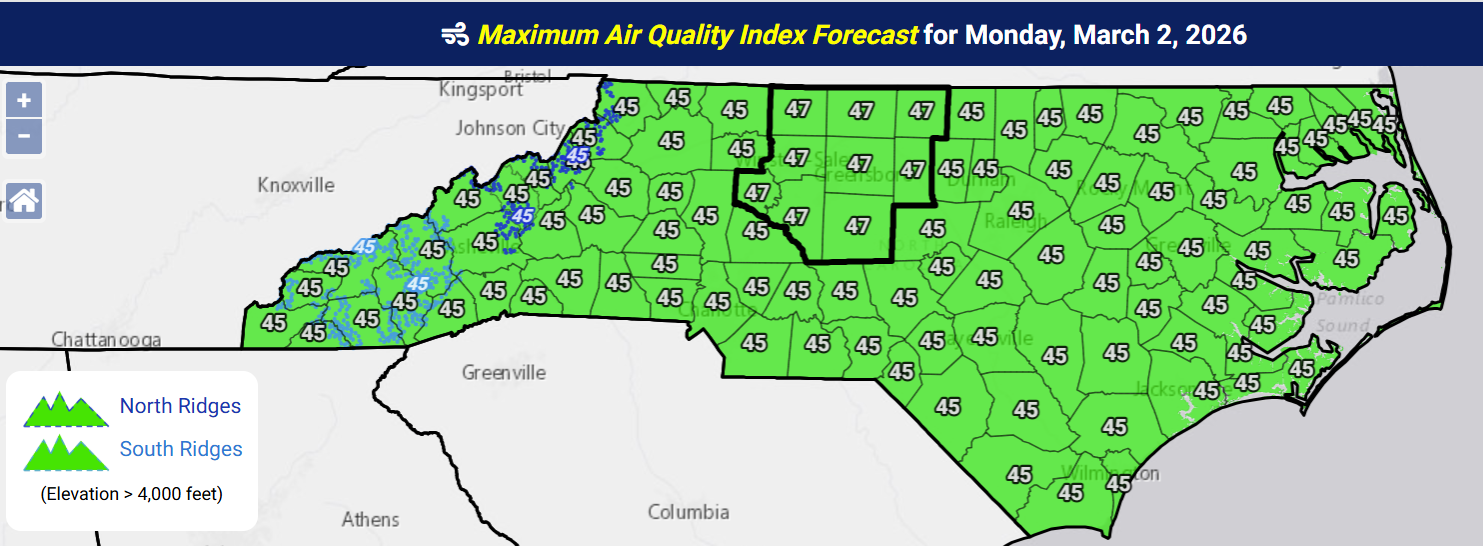

“The anti-wetlands provision in the Farm Act is disappointing and dangerous. If it becomes law, we estimate that the provision will leave at least half of the state’s 4 million acres of wetlands without federal or state protection. Wetlands hold and slow floodwaters. When they are paved over, downstream communities and farmland suffer increased flooding and dirtier water,” North Carolina Conservation Network Policy Director Grady McCallie said in a statement.

An analysis by the Southern Environmental Law Center found that, in the Neuse and Cape Fear River basins alone, about 900,000 acres of wetlands could be put at risk of pollution and destruction.

“Protecting wetlands protects our communities,” said Geoff Gisler, program director at the Southern Environmental Law Center. “By eliminating laws that have been in place for years, the legislature puts wetlands and our communities in harm’s way. This bill is the single most destructive action taken in North Carolina in decades — the legislature has abandoned our great natural resources, the rivers we depend on, and communities across the state.”

Supporter Spotlight

The bill — a 28-page mashup of agricultural and other provisions — passed the House 77-38 June 7 with the Senate voting 37-6 to concur with House amendments the next day. The primary sponsors were Sen. Brent Jackson, R- Bladen, Duplin, Jones, Pender and Sampson; Sen. Norm Sanderson, R- Carteret, Chowan, Dare, Hyde, Pamlico, Pasquotank, Perquimans and Washington; and Sen. Buck Newton, R-Greene, Wayne and Wilson.

It’s unclear whether Cooper will veto the measure, sign it or allow it to become law without his signature. The vote margins point to a likely veto override.

The North Carolina Home Builders Association had pushed for the rollback of wetland protections.

“This bill contains an important provision that restores the state definition of wetlands to language consistent with what remained in place for almost three decades in North Carolina,” Association Director of Legislative Affairs Steven Webb, said in an online video posted earlier this month.

The definition established by the Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers in the 1980s included all waters, wetlands and intermittent streams which, if degraded, could affect interstate or foreign commerce. This included wetlands adjacent to waters. The definition has been targeted numerous times over the years by litigation.

The Obama administration in 2015 expanded protections under the Clean Water Act, protections the Trump administration in 2020 repealed and replaced with the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which narrowed the definition of waters and wetlands subject to regulation. The definition was revised yet again and expanded by Biden administration this year, but the Supreme Court in May scaled it back in its decision.

“The uncertain meaning of ‘the waters of the United States’ has been a persistent problem, sparking decades of agency action and litigation,” according to the opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito and known as “Sackett v. EPA,” which also stated that, “The EPA’s insistence that ‘water’ is ‘naturally read to encompass wetlands’ because the ‘presence of water is ‘universally regarded as the most basic feature of wetlands’ proves too much.”

Mary Maclean Asbill, director of the North Carolina offices of the Southern Environmental Law Center, said it was difficult to describe how harmful the Farm Act is to North Carolina’s water quality, wildlife, fisheries and communities.

“North Carolina is setting the wrong example by failing to protect our wetlands after the Sackett opinion,” she said.

The law center noted that an acre of wetland can store about a million gallons of water, “so when developers and industry destroy wetlands, communities lose flood protection.”

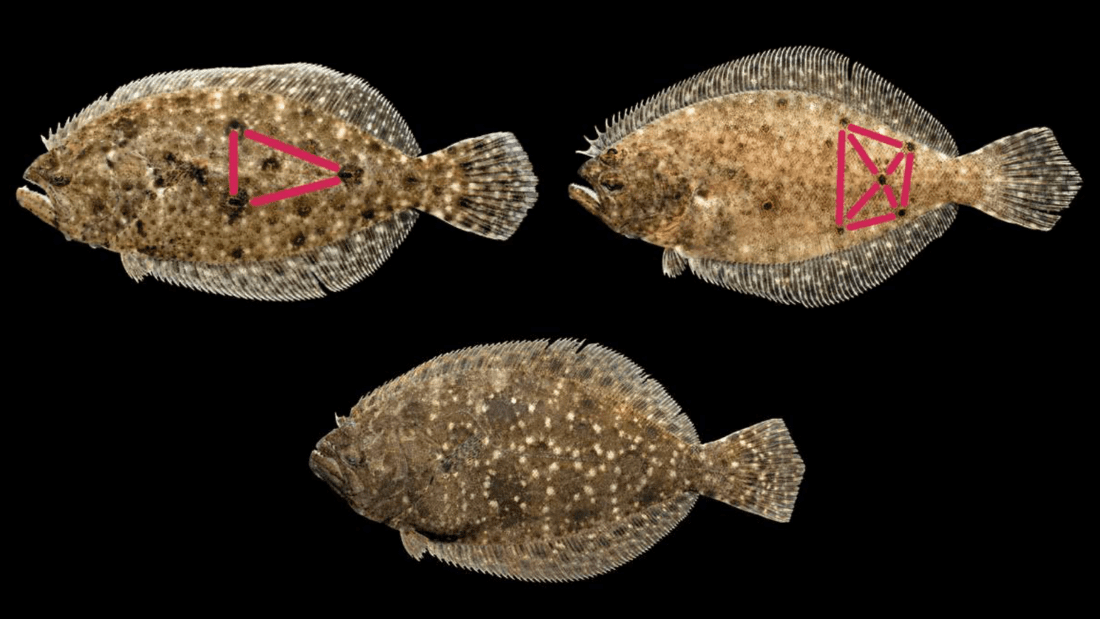

It also noted that the state’s nearly $300 million wild-caught seafood economy could be put at risk.