Fish that live in the seagrass meadows of North Carolina’s Back Sound seem to recover quickly from tropical cyclones, demonstrating a capacity for resilience in the face of disruptive shocks, reports a study published last month in Plos One.

The study, which used data collected over the course of 10 years, found that there was no significant difference in the fish communities before and after a storm, or during hurricane years and years with no hurricane. Dr. Y. Stacy Zhang, assistant professor in the Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at North Carolina State University and lead author on the study, hypothesizes that the resilience of the fish communities is tied to the integrity of the seagrass habitats that they depend on.

Supporter Spotlight

“Do they have a home to come back to, in the same way where if humans evacuate for a storm, do they have a home to come back to afterwards?” Zhang said. “That’d be changing the numbers.”

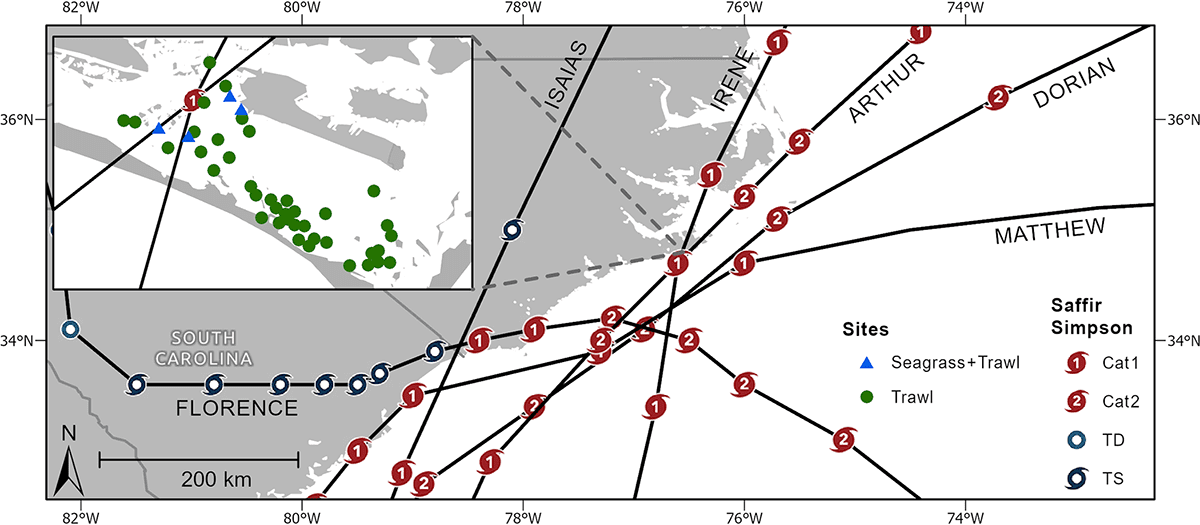

The study used data from a long-term trawl survey run by Dr. Joel Fodrie at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and consisting of two-minute trawls through seagrass meadows in Back Sound in Carteret County. They trawled monthly, randomly selecting a few sites to trawl each time and documenting how many fish came up and what types. The frequency and longevity of this sampling allowed the researchers to look for short-term trends — within three weeks of impact — as well as seasonal shifts.

“The fact that this project used 10 years of data and looked at multiple different storms, I think is a really beneficial approach to take,” Zhang said. “Because we are trying to capture some of that variability that you wouldn’t get if you looked at a single storm alone.”

The seagrass data was not from one standing data set, but sourced from multiple monitoring projects that had occurred in the area. These seagrass surveys indicated that the seagrass meadows were principally undamaged by storms.

Fish population dynamics are highly variable, and so are estuarine ecosystems. To document storm-related effects in spite of this variability, Zhang and her team ran multiple analyses on their data, examining things like fish community structure, tropical cyclone intensity and the difference between storm years and years without storms.

Supporter Spotlight

“(Estuaries) are such dynamic systems, they’re so variable just on a daily basis, it leads us to think that most of the fishes, the seagrasses, the oysters — all of those organisms are adapted in some way, shape, or form to withstand and live in this highly dynamic system,” Zhang said.

Dr. Christopher Patrick is the lead principal investigator at the Hurricane Ecosystem Response Synthesis Network, or HERS, a National Science Foundation-funded Research Coordination Network based out of the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences with co-principal investigators based at the University of New Hampshire, Florida International University and the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. HERS brings together specialists of different disciplines to develop a comprehensive understanding of ecosystem responses to tropical cyclones.

“Globally, the frequency of extreme events is increasing to the point where they’re not really extreme in a lot of cases anymore — they’re something that we should be expecting,” Patrick said. “We need to understand what the consequences of those changes in disturbance intensities, frequencies and distributions are for coastal systems so that we can plan accordingly.”

While these analyses didn’t show storms having strong overall impacts on fish communities, the figures do indicate that effects increase with storm strength. This suggests that a really severe storm would have a stronger impact.

“That’s the kind of thing that we may be seeing more of with warming waters,” Patrick said.

Because climate change implies more intense storms, Zhang said this could impact how resilient fish communities are in the face of these types of stressors in the future.

“We see that the fish communities and the seagrasses are pretty resistant to these pulse disturbances,” Zhang said. “But if, as it’s predicted that hurricanes are going to become more intense with climate change, is that going to actually start shifting the dynamic of whether or not these communities are resistant to the storms?”

How seagrass-associated fish communities will respond to the combined stressors of climate change, habitat changes and storms in the future remains an ongoing question. But, according to Zhang, there’s hope.

“The communities are pretty similar, regardless of whether it’s a hurricane year, or a nonhurricane year, or before or after the storm,” Zhang said. “There’s seasonality in the communities, but there’s no massive shift to the system as a result of the hurricane itself.”