This column is to introduce a series of special reports by Catherine Kozak, who attended the COP26 climate conference held earlier this month.

GLASGOW, Scotland — At a global event the size of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties, or COP26, North Carolina was barely a blip.

Sponsor Spotlight

Numerous people, even those from Western Europe and (gasp!) England, seemed to know little about our state, including the location of our famously angled Outer Banks coastline.

“It’s where the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is,” I said confidently.

“Ummmm.”

“It’s where the English first attempted to colonize America.”

Sponsor Spotlight

Polite smiles. “Oh?”

“It’s where the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk.”

“Ahhh!”

Of course, how much do we Americans know about the coasts of other nations, or even our own country? And yes, there were some Americans I spoke with at the conference who had no idea where the Outer Banks, and even North Carolina, were located.

During the Oct. 31-Nov. 12 summit, which opened ceremoniously on Nov. 3 with speeches from President Joe Biden and other world leaders, North Carolina was merely part of the U.S that shares the alarming global impacts from a changing climate: rising and warming seas, hotter summers, intensifying rain and wind during storms.

As is the case in the rest of the world, wildfires, flooding and drought are likely part of North Carolina’s tomorrow because they’re part of North Carolina’s today and yesterday. It’s just a matter of timing and degrees.

Every state, every region, every nation, has different levels of threat, but judging from the breadth of attendees at the conference, every corner of the world feels under threat, whether current or looming.

And on the periphery, most of the world has been stressed by the prolonged pandemic, divisive politics and an uneven economy. In a word, that is the value of such global events: connection. Traveling is humbling and enlightening at the same time, but more importantly, it breaks us out of the enclosed room of our lives.

Even in the other world-ness of a sprawling mini-city of the COP, participants, observers, journalists were joined in a collective, sprinting from hub to hub for conferences, presentations and meetings, in several different “zones,” which often added up to many city blocks of distance. One man shared that another participant had told him that he had walked 30,000 steps the previous day, which adds up to about 15 miles.

Big screens in the Action Zone — where a large blue Earth hovered over an expansive gathering area filled with tables and chairs and lined with broadcast areas and small meeting rooms — displayed interviews taking part on a stage.

On Monday, Nov. 8., the room was abuzz about former President Barack Obama’s visit, which took place in another area where people had lined up to grab limited seats to watch in person. International press coverage of Obama’s speech was glowing, making our former president the big hit of the summit. Two days earlier, more than 100,000 marchers filled the streets in Glasgow, led by climate activist Greta Thunberg and other young people, to demand substantial and urgent action on climate change.

The second week concentrated on the meat and potatoes of the negotiations, which focused on finding consensus among global participants with disparate wealth, resources, populations, vulnerability, impacts and emissions contributions. Indigenous members of tiny island nations worked shoulder to shoulder with powerful representatives of wealthy nations into the night hours seeking solutions.

During the week, U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry could be seen dashing down long hallways, trailed by reporters. Kerry was also an active negotiator at the 2015 COP21 in Paris, when he was Obama’s secretary of state. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, several Congress members and 13 cabinet secretaries also showed up — Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg attended remotely — with some of their images flashing spectrally on various screens throughout the conference.

On Nov. 13, after days of intense negotiations, an agreement was announced. Hammered out by diplomats representing about 200 nations, the parties pledged to return next year to strengthen limits on greenhouse gas emissions and to encourage richer nations to double funds to help developing countries cope with the impacts of climate change.

It was an imperfect conclusion to the ambitious two-week gathering that hosted about 30,000 attendees from all over the world, including North Carolina scientists from Duke University and RTI International, among others.

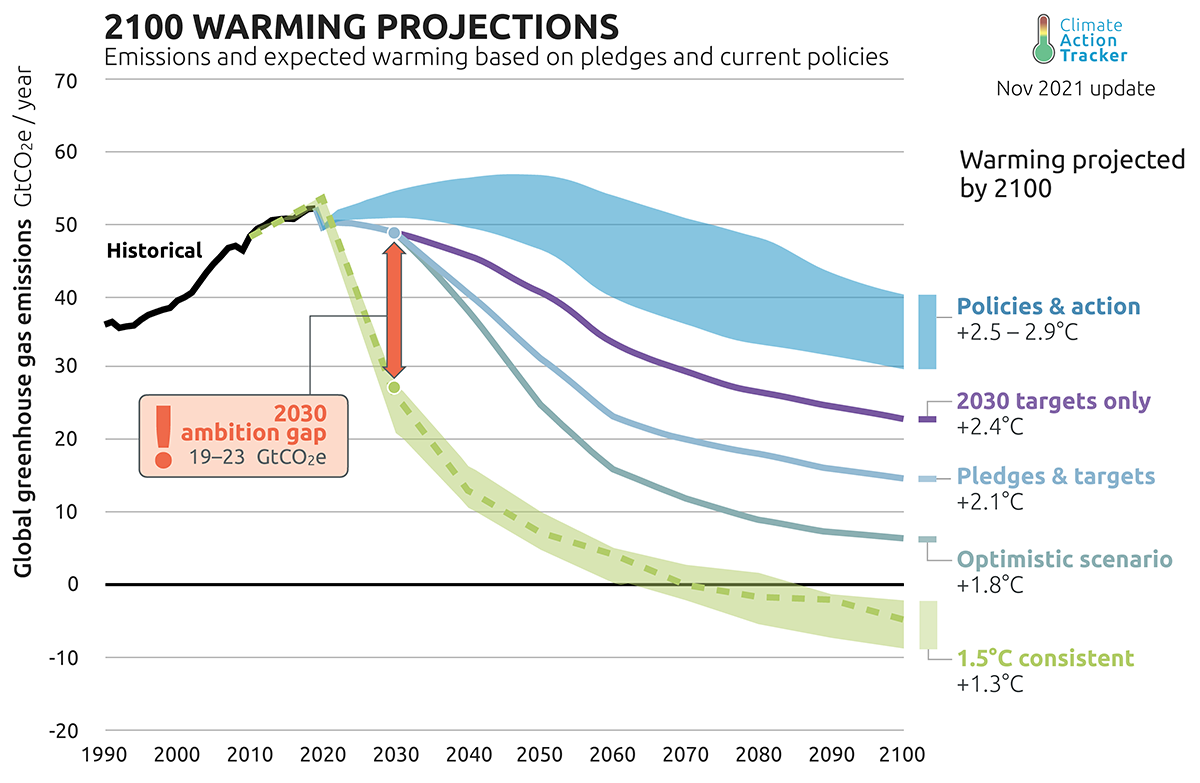

In Glasgow, Biden had characterized the meeting as the world’s “last chance” to save the planet from the impacts of climate change. World leaders at the start had set a goal to reduce emissions enough to cap global temperatures increases at 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.5 Celsius, compared with preindustrial levels.

Biden pledged to cut U.S. carbon emissions in half by 2030, reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

But even with the nations’ new pledges and targets to reduce fossil-fuel emissions and limit deforestation, warming is projected to be 2.1 degrees Celsius, or 3.78 degrees Fahrenheit, by 2100, according to research group Climate Action Tracker.

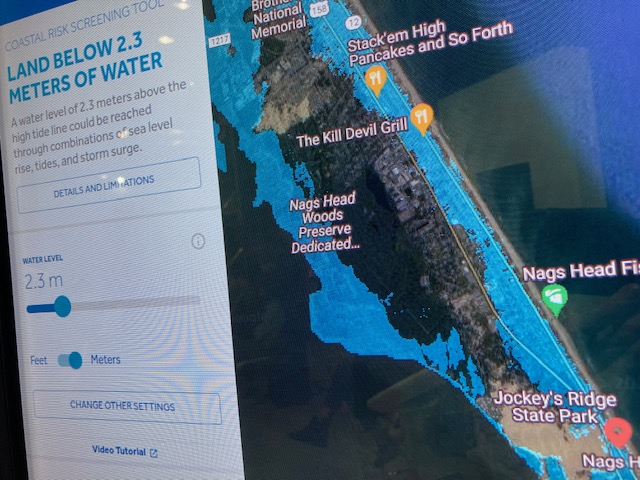

At the U.S. pavilion at the conference, a big interactive map provided by Climate Central, a scientific data research group invited attendees to enter their hometown location to see the impact of sea level rise under different scenarios. Nags Head, where I live, was shockingly blue under the higher emission projection.

Despite falling short of the initial goal, the summit harnessed unanimity between global leaders that more must be done to prevent climate disaster. And compared with Paris’ significant, but at times aspirational, climate pledges, the Scotland agreement included more realistic rules meant to provide more transparency and accountability in tracking countries’ actions.

“It’s meek, it’s weak and the 1.5 Celsius goal is only just alive, but a signal has been sent that the era of coal is ending,” said Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International, described the climate deal to the New York Times Nov. 13. “And that matters.”

US, global commitments

The following actions were announced during the summit:

- The Biden administration pledged carbon-pollution free electricity production by 2035 and to permit 25 gigabytes of renewable energy on public lands by 2025.

- The U.S. Department of the Interior committed to develop offshore wind projects, with a goal to deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030.

- The U.S. State Department announced that an agreement with the European Union and partners had been launched to reduce global methane emissions. The Global Methane Pledge represents more than 100 countries and 70% of the global economy as well as about half of the human-produced methane emissions.

- COP26 negotiators also created new trade standards under Article 6, a provision of the 2015 agreement from the Paris climate conference that deals with carbon credits. The updated standard includes more transparency on selling and trading of carbon offsets.

- About 130 countries collectively promised billions of dollars to stop deforestation by 2030, and dozens of nations pledged to phase out coal power and sales of vehicles that use gasoline.

- For the first time, the COP agreement included a vow to “phase down” coal power and government subsidies for oil and gas.

- The U.S. joined the COP26 High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, or “Ocean Panel,” a multinational initiative focused on harnessing the power of the ocean to reduce emissions, provide jobs and food security, improve climate resilience and sustain biological diversity, according to a U.S. State Department press release.