As more and more people move to the coast, there is a constant struggle between development and protecting our coastal environment.

We all need to be working together to resolve the complex issues facing our North Carolina coast. Currently, this is not happening. Standing at the forefront between future development and the environment is the United States Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps is an engineer formation of the United States Army that has three primary missions: Engineer Regiment, Military Construction and Civil Works. These engineers build sea walls, renourish beaches, dredge inlets and give approval for others (towns and contractors) to perform activities such as the construction of terminal groins and creating new or restoring existing navigational channels by dredging. Another important mission is aquatic ecosystem protection and restoration. Therefore, and unfortunately, the future of our coastal environment is not in the hands of natural resource agencies and coastal scientists, but rather in the hands of engineers.

Supporter Spotlight

A generalized difference between engineers and coastal scientists is that scientists are trained to understand natural systems while engineers are trained to manipulate the natural systems. Protecting our coastal environment should require and combine both; the engineers’ practical problem-solving expertise along with the scientists’ expertise on how nature works. Unfortunately in problem solving, coastal engineers usually ignore the scientific concerns expressed by coastal scientists. It is this scientific uncertainty about natural events that can undo engineering interventions on the coast. In some cases, the consequences of intervention can take several decades to become apparent. This makes it difficult for the general public to access applications and make the connection between Corps intervention and consequences it triggers.

The Corps recently approved permits to place a terminal groin on the east end of Ocean Isle Beach and to perform new dredging to create a navigational channel in Jinks Creek at Sunset Beach. What does the science say about these two projects? What are the probable future consequences the taxpayers, residents and vacationers of Ocean Isle Beach and Sunset can expect?

Example 1. A terminal groin was approved for the east end of Ocean Isle Beach because the beach in that area is eroding. A groin is a long, solid structure that extends out into the water, perpendicular to the shoreline, and is typically made of cement or rock. Groins prevent erosion by trapping the longshore transport of sediment on the updrift side of the groin. Wave actions naturally remove sand from the beach and this sand enters the longshore current and moves the sand parallel to the shoreline. In Brunswick County beaches this sand moves east to west. Terminal groins act like dams, physically stopping the movement of sand. Groins do result in a buildup of sand on the upstream side of the groin, which is precisely what they are designed to do. However, the areas further downstream are cut off from the natural longshore transport thereby triggering more erosion.

Figure 1 demonstrates that once the first groin is constructed additional groins will be required to protect the beach downstream. This figure shows a series of six groins along a beach. Notice the erosion downstream from the groin at the top of the figure.

On the other hand, soft stabilization such as beach nourishment, dune building, marsh systems and living shorelines should be considered before intervention with hard structures like terminal groins. Soft structures will not subject the beaches of Ocean Isle Beach and eventually Sunset Beach to a series of terminal groins.

Supporter Spotlight

How can placing a terminal groin on Ocean Isle Beach be considered beach restoration when it will trigger more erosion? If a terminal groin is placed on the East end of Ocean Isle Beach how many future, additional groins will be needed? What will be the cost? Who will pay?

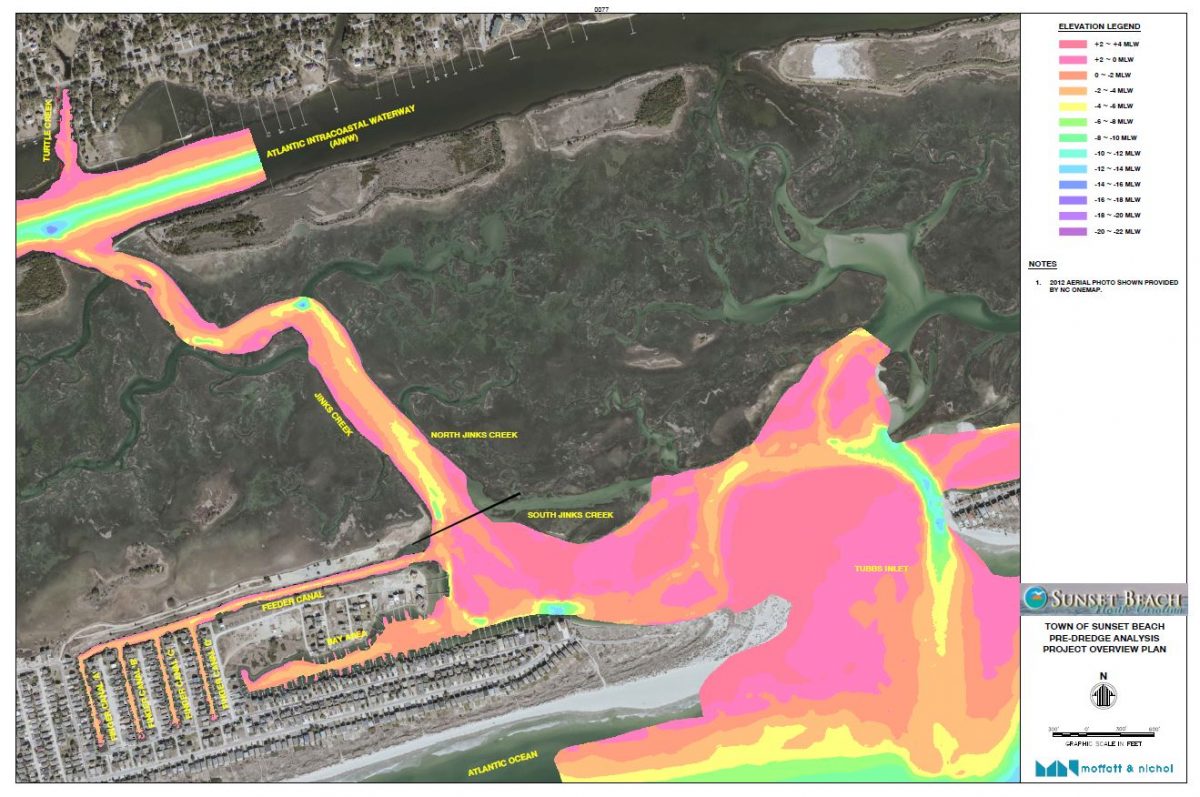

Example 2. The Corps recently approved a Sunset Beach permit to create a new navigational channel in South Jinks Creek, which is a naturally occurring shallow water tidal creek that has never been dredged before. Figure 2 shows the location of Jinks Creek on the East end of Sunset Beach. Jinks Creek via Tubbs Inlet connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. Just west of South Jinks Creek are the feeder canals and Canal Bay area. North Jinks Creek is surrounded by salt marshes which have been designated primary nursery areas and thus cannot be dredged. The town originally proposed to dredge all of Jinks Creek along with the feeder/canals and Canal Bay but, due to the high density of oyster beds North Jinks Creek was removed.

Scientists have clearly expressed concerns that dredging a 1,700-foot-long, 80-foot-wide navigational channel that is 5 feet mean low water level in South Jinks Creek will increase the risk of flooding and erosion after storm surges on the east end of Sunset Beach. The engineering consulting firm Moffat and Nichol hired by the town said their computer modeling indicates there will not be any increase of flooding or erosion. The engineers state their modeling data estimates the maximum flood increase to occur in South Jinks Creek may be equal to an order of only 1/64 of an inch.

North Carolina State University professor emeritus Dr. Len Pietrafesa, the Burroughs and Chapin Scholar at Coastal Carolina University, Dr. Paul Gayes, a professor of marine science and geology at Coastal Carolina University and executive director of the Burroughs and Chapin Center for Marine and Wetlands at Coastal Carolina University, and Dr. Shaowu Bao, associate professor at the Coastal Science Center at Coastal Carolina University, using the very same computer program but with additional input data, disagree.

According to Dr. Pietrafesa, the study done by the consulting firm did not take into account nonlocal forcing due to wind set up at the mouths of tidal inlets, such as Tubbs Inlet that connects to South Jinks Creek, which are stochastic, or cannot be precisely predicted, and can overwhelm the amount of volumetric transport that can be driven into the system, particularly for South Jinks Creek. There already is major erosion in this area as shown by the extensive network of sandbags where Tubbs Inlet joins South Jinks Creek. If the three independent academic scientists are correct, the property owners in this area can expect more sand bagging on the rest of South Jinks Creek and possibly in Canal Bay. Sandbags are most likely only a temporary fix. What is next, other hard structures like bulkheads or sea walls? What will happen to the property values in this area?

After the initial dredging, maintenance dredging will be required every few years to keep the unnatural channel open. What will be the escalating costs of the required additional dredging? Who will pay for them?

Another consequence of dredging South Jinks Creek is that it will increase the sediment load deposited in North Jinks Creek. This will bury the high density of oyster beds. Oysters are a “keystone” species, meaning their removal could dramatically change the ecosystem. What will be the ecological impact on North Jinks Creek and the surrounding primary nursery areas? How can dredging a shallow-water tidal creek that has never been dredged before be considered aquatic ecosystem protection and restoration?

In addition, the increased sediment load deposited in North Jinks Creek will most likely require that North Jinks Creek be dredged followed by more maintenance dredging. Again, what will be the escalating costs and who will pay?

The civil works side of the Corps’ mission includes:

- Navigation.

- Flooding and storm protection.

- Aquatic ecosystem restoration.

If you protect wisely you don’t have to restore. They are naturally a function of each other. If we are serious about attempting to protect what little natural environment, we have left we must convince the engineers of the Corps to collaborate with the independent academic scientists who have dedicated their professional lives to studying our coast. True collaboration leads to win-win solutions.

To stimulate discussion and debate, Coastal Review welcomes differing viewpoints on topical coastal issues. See our guidelines for submitting guest columns. The opinions expressed by the authors are not those of Coastal Review or the North Carolina Coastal Federation.