First of two parts. Updated with map link, boundary clarification.

The Albemarle-Pamlico estuary is one of the largest and most productive estuaries on the Atlantic Coast, with the second largest submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, resource in the continental U.S., said Jud Kenworthy, a research biologist who is currently adjunct faculty in the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s department of biology and marine biology.

Supporter Spotlight

Researchers recently have begun tracking SAV trends on the state’s coast and stress that it’s best to maintain and preserve SAV, which are home to hundreds of thousands of fish and invertebrates, rather than try to replant and restore SAV once it’s gone. This two-part series will examine the effort and its role in monitoring the health of the coast.

As Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership Director Bill Crowell said, “Understanding the status of our SAV habitats allows us to be better informed for the management of this resource and understand how our actions may affect its health,” which is why APNEP has coordinated and published two maps of submerged aquatic vegetation in the Albemarle-Pamlico region.

APNEP works with citizens and organizations to identify, protect, and restore the resources of the Albemarle-Pamlico estuarine system.

With funding from APNEP and field and technical support from the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, Beaufort Laboratory, digital data of coastal SAV was mapped for imagery years 2012-2014. This is the second effort led by APNEP to map the distribution, abundance and change of SAV in North Carolina, according to APNEP.

The SAV Team published the first map, a baseline map, of SAV in 2011 using data from aerial flights taken between 2006 and 2008 along the North Carolina and southern Virginia estuarine coastlines. This included the coastal zone that lies within the APNEP regional boundary, which is from Bogue Inlet north to Back Bay, as well as Bogue Inlet south to Masonboro Inlet.

Supporter Spotlight

Because the aerial surveys were conducted infrequently due to funding and could only monitor changes in large areas that did not have diminished visibility due to turbid waters, APNEP in 2014 began coordinating a SAV Sentinel Network that combines boat-based sonar and video technology with in-water observations to track SAV in the sounds, according to APNEP. The 2012-2014 map provides an update to the higher salinity areas of the 2006-2008 SAV map in the regional boundary.

Visitors to the online resource can compare the SAV extent and density on the map by clicking the check boxes in the “Layers” block on the right side of the map to toggle the 2013-2014 or 2006-2008 map data on and off. More information about how the data was collected, as well as the map data itself, is available on the DEQ ArcGIS Online website, Crowell said.

Crowell explained that the Albemarle-Pamlico region has more than 136,000 acres of submerged aquatic vegetation – putting it in the top three states in the country for SAV abundance. This estuarine system also contains half of the juvenile fish habitat from Maine to Florida, making the status of its SAV an issue of regional and perhaps national importance.

“SAV plays a crucial functional role within our coastal ecosystems. One study stated that a single acre of grasses may support as many as 40,000 fish and 50 million small invertebrates,” he said. “Additionally, these grasses improve water quality by absorbing excess nutrients, generating oxygen, and reducing the sediment moving about in the water column. In some areas they help to protect shorelines from erosion, by decreasing wave energy.”

Kenworthy, who retired in 2011 from the NOAA Beaufort Lab after 33 years of federal service, focused during his research career on the ecology, habitat utilization, conservation and restoration of seagrass and SAV habitat. After retiring, he continued to work with APNEP as co-lead of the SAV monitoring and assessment team.

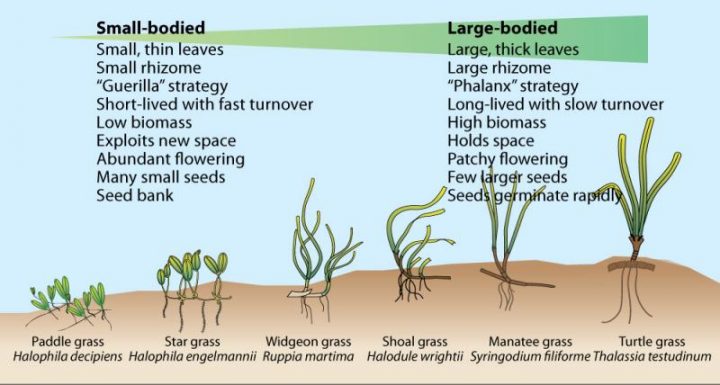

Kenworthy explained that submerged aquatic vascular plants are that have adapted to live almost exclusively underwater in both seawater, more commonly called seagrasses, and lower-salinity brackish and freshwater environments, more commonly referred to as SAV.

“This is why we find two personalities of SAV throughout coastal North Carolina, SAV and seagrass, but we often refer to them all as SAV,” he said. However, unlike their submerged counterparts, macroalgae, SAV have roots and rhizomes that anchor them in the substrate and a leaf canopy that slows currents and baffles wave energy.

“They function much like the grasses that live on your front lawn. SAV trap and stabilize the soil they grow on, as well as protect adjacent emergent shorelines,” Kenworthy said. The productivity and biomass of SAV store large amounts of carbon and other nutrients and, along with the sediment stabilizing capabilities, they serve to maintain and promote superior water quality, benefiting the entire estuary.

“Ecologically, SAV provide shelter and food to an incredibly diverse community of animals, from tiny invertebrates to large fish, crabs, turtles, marine mammals, shorebirds and waterfowl. Seagrasses provide many important services to humans directly and indirectly, but many seagrass meadows have been impacted by human activities,” he added.

Crowell explained that before APNEP started coordinating efforts to map and monitor the region’s submerged aquatic vegetation, there were no long-term SAV-monitoring programs in the state that could provide reliable information about how this resource has been changing over time.

In 2001, APNEP established the Albemarle-Pamlico SAV partnership with various state and federal agencies to collaborate, with the long-term goal of determining where the region’s underwater grasses are located and if their overall extent and density is changing over time, according to Crowell.

Additional partners from nongovernmental organizations and academic sectors joined to further the mission of the open-membership group. The effort was boosted with the development of Coastal Habitat Protection Plan, a document used by the state Department of Environmental Quality to guide habitat decisions as they relate to fisheries.

In 2004, APNEP created a memorandum of understanding to formalize partner interactions to move forward with the joint effort to address the identification, status and restoration of SAV habitat.

The memorandum was signed in 2006 by all participants, which includes nine state agencies, nine academic institutions, two nongovernmental organizations and four federal agencies, thus formally creating the “SAV Partnership.”

Crowell explained that the initial priority has been mapping the region’s SAV to determine if and where action needs to be taken.

“APNEP/SAV partnership released the first map in 2011 for images collected 2006-2008. Given the dynamic nature of the habitat, we are still trying to get a good understanding of its distribution and condition. We then want to document how things were and how its changing. Protecting the region’s SAV is far less expensive that it is to replant and restore SAV once it has disappeared,” he said.

Crowell said to protect estuarine water quality, “Avoiding overuse of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides makes a difference in water quality far downstream. Boaters can avoid tearing up shallow grass beds with boat props, avoid bottom-disturbing fishing gear that rips up SAV, and utilize the N.C. Clean Marina Program. State and local government efforts to reduce nutrient and sediment pollution, as well as stormwater runoff, also go a long way towards creating the conditions SAV needs to flourish.”

The Clean Marina program is a nearly 20-year-old state effort to show that marina operators can help safeguard the environment by taking steps that go beyond regulatory requirements.

Crowell said that it should be noted that the SAV partnership was necessary to generate the funds and personnel necessary to start the mapping efforts.

“Today, we still rely on numerous partners to do this work. This spring, many volunteers provided daily water quality reading and weather reports to us so we could schedule the flights under the right conditions to capture the images,” he said.

In addition to aerial mapping, Cowell said there has been an effort over the past decade to develop protocols for coordinating data collection across the region.

“Since 2014, researchers from East Carolina University and other SAV Team members have monitored SAV in the low-salinity waters of the sounds via boat-based surveys that use underwater sonar, cameras, and square quadrats to collect SAV data at ‘sentinel sites’ over time,” he said. “In the long term, the goal is for the combination of semi decadal aerial surveys of the higher salinity waters near the barrier islands and more frequent boat-based surveys throughout the region to allow the SAV Team to obtain an ongoing assessment of how the state’s submerged aquatic vegetation is changing over time.”

Next: Canaries in the coal mine