North Carolina, Colorado and Michigan, three states with water contaminated by poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are the focus of a three-year study to better understand the extent of contamination.

A team of researchers will look at to what degree these man-made chemicals accumulate in foods such as vegetables, fish and eggs harvested in an affected community. Also, the team is to collect data to better predict how the PFASs move through soil into groundwater. The goal is to answer the question, “When PFAS contaminate a drinking water source, is it enough to just treat the water people drink? Or do state and local agencies need to do more to limit residents’ exposure?” according to an announcement earlier this year by Michigan State University.

Supporter Spotlight

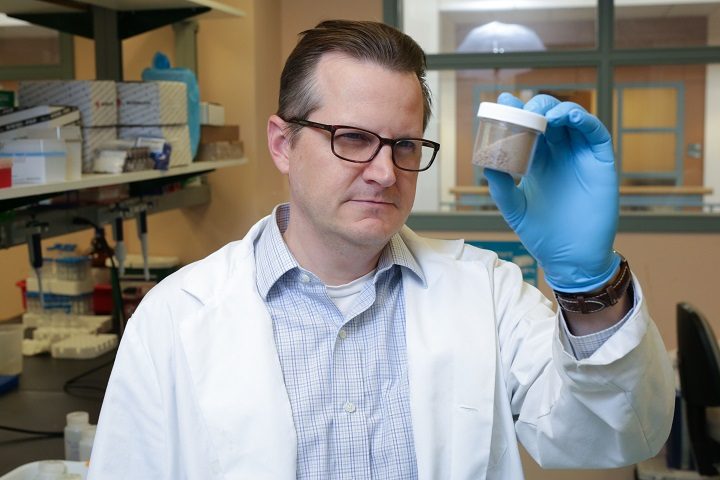

Chris Higgins, a PFAS expert and professor of civil and environmental engineering at Colorado School of Mines, is leading the project.

“What we’re trying to do is at least start to tackle that question of how important are those other routes of exposure that are not coming from the drinking water, in terms of the overall exposure to these chemicals,” Higgins told Coastal Review Online in an interview.

Along with Michigan State University, Higgins will be working with researchers from North Carolina State University, Duke University and the Colorado School of Public Health at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

The $2.46 million study called PFAS-UNITEDD: Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substance – U.S National Investigation of Transport and Exposure from Drinking Water and Diet is being funded with $1.96 million from the Environmental Protection Agency National Center for Environmental Research. There is a $262,500 cash match from the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory’s Challenge Grant fund through the General Assembly and additional in-kind contributions have been provided by industry partners Jacobs, CDM Smith and others.

The three states in the study have different sources of contamination.

Supporter Spotlight

Here in North Carolina, Chemours’ Fayetteville Works has been identified as a source of PFAS contamination in the Cape Fear River, the drinking water source for Wilmington. In Colorado, firefighting foam used at a nearby military installation likely contaminated groundwater and soil with PFAS in three towns south of Colorado Springs. And PFAS contamination has been identified as a byproduct of industrial activity at several sites in Michigan.

Higgins said that with this project, state and local community decision makers can be provided with information on what to do when these compounds are discovered.

“The real focus, and the thing I think is most exciting about this project, is trying to answer the question that a lot of folks have been asking, which is, ‘If you stop the exposure via contaminated water, is that enough to reduce the exposure to background levels in the population?’” Higgins said.

He said scientists understand that contaminated drinking water is the dominant source of exposure. “However, there are other routes you can be exposed,” including using contaminated water to irrigate a garden. “I think that’s a great example because the compounds are being taken up by the crops, you’ll eat them and be exposed to them that way.”

Higgins said that the grants are for three years and work officially began May 1. The team is currently working on the first step, which is to have the plans approved for the research, a part of the terms of the grants.

The team aims to get as much done as quickly as possible in those three years but probably won’t have preliminary results for at least year. “It’s going to take time to set up these studies, there’s a lot of people involved, and it will take time,” he said.

Higgins emphasized that this project will not consider the health effects of these chemicals, rather it will look at understanding how residents are being exposed. “Is eliminating it in drinking water the only thing you need to do, or do you need to consider these other pathways?”

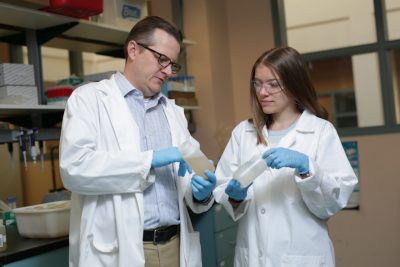

Detlef Knappe, a professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at N.C. State, explained that in North Carolina, the recently identified PFAS, such as GenX and Nafion byproducts, have been emitted into the air and water for decades.

“For some of the compounds, nothing is known about their migration through soil into groundwater and their uptake by plants and animals that serve as sources of food,” Knappe said in a statement. “This study will allow us to develop information that will help answer important questions.”

Knappe told Coastal Review Online that the hope is to be able to predict how and how quickly contamination spreads. “How fast do (PFAS) travel from the land surface through soil into groundwater and how fast they travel once they are in the groundwater?”

He said researchers also expect to gain a greater understanding about the presence of both traditionally studied and poorly understood PFAS in food.

“This will allow us to determine whether food is an important route of PFAS exposure in addition to drinking water,” he said. “This information is important for understanding how long it will take to remediate contaminated groundwater sites. We know that poorly understood PFAS are present in Colorado, originating from firefighting foam, and in North Carolina, originating from Chemours.”

Knappe was tapped to be part of the project because of his extensive research on PFAS, such as GenX and other fluoroethers in North Carolina drinking water. It was Knappe’s work that in 2016 brought to light the presence of GenX in untreated drinking water drawn from the Cape Fear River and noted the difficulty in removing the compound via standard water treatment.

“Also, our ongoing GenX exposure study, which is led by Jane Hoppin, is providing an important foundation for this project because we are studying the levels of traditionally studied and poorly understood PFAS in North Carolinians, who have been exposed to these PFAS for decades near the Fayetteville Works manufacturing plant and in the Wilmington area,” Knappe said.

Hoppin, an associate professor of biology at N.C. State, and John Adgate, chair of Colorado school of Public Health’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, are leading the GenX exposure study with funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Oregon State University is leading a companion study funded by the Environmental Protection Agency that will look specifically at PFAS toxicity and which compounds are most worrisome for human health. There is also to be an advisory board composed of PFAS experts, state decision makers and stakeholders from PFAS-affected communities, according to the announcement.

Hoppin explained that she is the principal investigator for the study project to assess PFAS exposures including GenX among Wilmington and Fayetteville residents.

“A similar study in Colorado was funded the month after ours was and we had been eager to compare our results and to combine, if appropriate, to have a larger sample size to evaluate PFAS exposure,” she told Coastal Review Online. “When the EPA announced the call for proposals, it was the opportunity to allow us to work together and build both local and national knowledge on this topic.”

Hoppin said that while Colorado and Michigan both have drinking water sources impacted by PFAS, the chemicals present may differ from those in North Carolina, where both groundwater in the Fayetteville area and surface water in Wilmington are contaminated.

“Many of the chemicals found in the Wilmington drinking water are unique to the manufacture of fluorochemicals, while other PFAS are those present in people around the globe. By comparing the exposure patterns of three distinct populations, we will potentially be able to learn more about PFAS as a chemical class and be able to predict how new chemicals will move through the environment,” she said. “We are planning to compare the fingerprints of PFAS in blood across the cohorts. Other aspects of the study will evaluate how chemicals move through the environment and whether PFAS are present in home grown fruits and vegetables.”

Because the chemicals in North Carolina are unique to North Carolina, Hoppin said, it is important to learn whether these chemicals behave the same way as other chemicals. “We will be able to learn how similar and how different these chemicals behave in the environment and in our bodies.”

The Michigan study will be led by co-principal investigator Courtney Carignan, assistant professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at Michigan State.

“Michigan launched a comprehensive monitoring program for PFAS in public drinking water and has discovered over 30 sites with elevated concentrations and over 100 with PFAS detections,” Carignan said in an interview. “The Michigan cohort will focus on one of the sites, likely Parchment.”

The public water supply system of Parchment, Michigan, in July 2018, became the first system in the state with PFAS results exceeding the EPA’s Lifetime Health Advisory level of 70 parts per thousand of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, or PFOS, and perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, according the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. The suspected source of contamination is the Crown Vantage Property, site of a former landfill used to dispose of papermaking waste, a historic wastewater treatment plant, former settling lagoons and a former mill property.

As an environmental health researcher who works with PFAS-exposed communities, Carignan said the study was designed to answer some of the residents’ most frequently asked questions.

“Community concerns extend beyond drinking water to include locally grown, produced and captured foods such as garden produce and fish,” Carignan said. “Our study will measure levels of PFAS in those foods and model exposure for both children and adults. Results will be shared with the community and health department and will also be useful to other communities dealing with PFAS contamination.”

Susan Gordon, a member of the advisory board and former manager of a community farm near Colorado Springs that closed due to PFAS contamination, said that past PFAS research had focused on drinking water as a pathway.

“There are a lot of questions around other ways that community members may have been impacted,” Gordon said in a statement. “As a farmer who was significantly impacted by PFAS, no one could answer my questions about the possibility of exposure through the vegetables we grew on the farm and the animals we raised. The fact that Dr. Higgins and his team and the EPA are looking at this is hugely important, because all potential pathways for exposure need to be addressed. Hopefully this research will provide additional scientific justification for adequate protective regulation.”