Since news first broke about the presence of GenX in the Cape Fear River and the Wilmington-area water supply, there have been two arcs to the story.

There are the immediate concerns over the safety of drinking water in Wilmington and in the vicinity of the Chemours manufacturing facility in Bladen County, and there’s the open question about what the state will do going forward to monitor and regulate GenX and the growing universe of unregulated emerging contaminants.

Supporter Spotlight

This fall could prove pivotal in each area as deadlines approach in both legal and regulatory actions and a new university-led effort works toward creation of a statewide network aimed at monitoring and research of GenX and other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

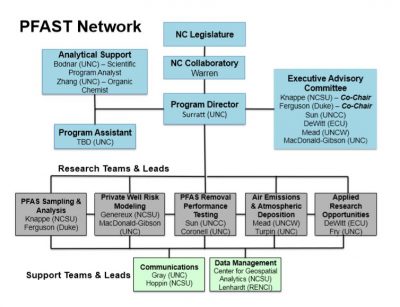

Jason Surratt, a professor and researcher at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health, was recently named program director for the new PFAS Testing Network. Surratt said the group, which was established through the university’s North Carolina Policy Collaboratory and includes researchers at six universities, will lay out plans, organization and goals for the network Sept. 28 during a PFAS forum at Duke University.

The studies are being led by North Carolina State University professor Detlef Knappe, one of the lead researchers in establishing the presence of GenX in the Wilmington area’s water supply and Lee Ferguson, a Duke University environmental engineering professor who has advocated for a more comprehensive regulatory and monitoring system.

The advisory board for the project includes Knappe, Ferguson, University of North Carolina Charlotte assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering Mei Sun, associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology Jamie DeWitt from East Carolina University, chemistry and biochemistry professor Ralph Mead at University of North Carolina Wilmington and University of North Carolina Chapel Hill groundwater researcher Jacqueline MacDonald-Gibson.

Surratt said the organization has been moving quickly and has already received its first round of funds from a $5,013,000 appropriation to the collaboratory in this year’s adjustment to the state budget.

Supporter Spotlight

A special provision in the budget legislation directs the collaboratory to identify faculty, equipment and other resources and coordinate them to “conduct non-targeted analysis for PFAS, including GenX, at all public water supply surface water intakes and one public water supply well selected by each municipal water system that operates groundwater wells for public drinking water supplies as identified by the Department of Environmental Quality, to establish a water quality baseline for all sampling sites.”

Another section of the provision directs the collaboratory to set up research on modeling of PFAS discharges and potential contamination of private wells, along with test methods for removing PFAS. It also calls for a study of air emissions and atmospheric deposition, which has been one of the primary areas of focus of Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, work around the Chemours plant.

In an email response to Coastal Review Online, Surratt said the PFAS Testing Network has set up a management group based at the Gillings School of Global Public Health, formed research and support teams and work has started on setting up a system for the baseline assessments. (See chart)

“Hiring is underway for the teams or people are already in place, and we expect work to begin in October,” he said. “DEQ has provided us their list of required sampling sites established in the legislative language, and we are discussing logistics on how sampling at these 348 sites will be carried out.”

The list includes 190 public surface water intakes and 158 municipalities with at least one public water supply well.

Surratt said the group has also started its outreach efforts.

“Numerous stakeholder meetings have already taken place to brief and listen to interested parties, including the Chemical Manufacturers Association, numerous environmental advocacy groups, and DEQ,” Surratt said. “We expect this dialog to continue and be ongoing throughout the project.”

The network is required to report its findings on the baseline sampling to the Environmental Review Commission, DEQ, the Department of Health and Human Services, or DHHS, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, no later than Dec. 1, 2019. The collaboratory’s first quarterly report on the network is due no later than Oct. 1.

Science Panel OKs Health Goal – With Caveats

As the new network cranks up, work on mitigating the effects of GenX downstream and downwind of the Chemours plant continues. Last week, a panel of scientists, including Knappe, concurred with the state’s health goal for GenX levels in surface water set by DHHS.

The health goal is a target amount but has no regulatory effect. The goal for GenX was initially set at 71,000 parts per trillion, or ppt, but was later adjusted to 140 ppt when DHHS took into account the risk of exposure over time to sensitive populations such as pregnant women and infants.

Chemours has since argued in favor of the original health goal.

The Science Advisory Board, which reports to DEQ Secretary Michael Regan and DHHS Secretary Dr. Mandy Cohen, said based on a review of the research available, they agreed with the current health goal.

“The Board commends the reference dose developed by DHHS to DEQ as the foundation for establishing health-protective environmental standards,” according to a draft report released at the meeting. A final version of the report is expected within two weeks.

The science board also acknowledged that GenX and other PFAS substances are a moving target and said that the health goal and the state’s approach should be reviewed as new information becomes available, particularly expected action from the EPA, which has not established a federal standard but could do so sometime this fall.

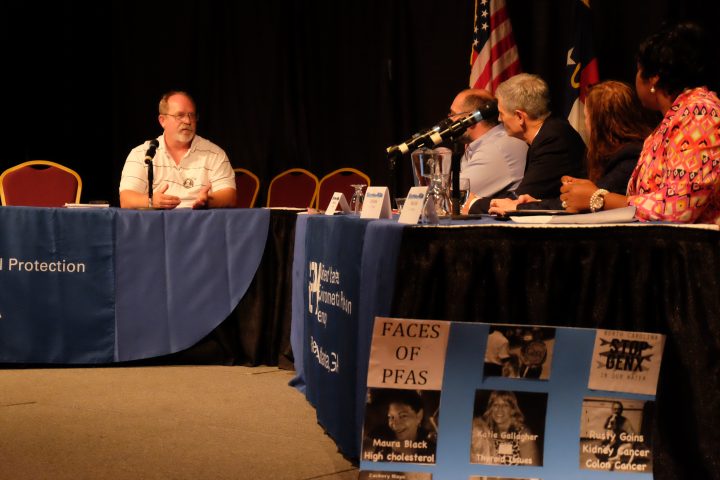

The EPA held its first meeting on GenX earlier this month. The Fayetteville community stakeholder meeting held Aug. 14 drew several hundred attendees and featured presentations by EPA and other officials. Residents demanded more aggressive EPA action.

The board also suggested DEQ continue to study the air emissions, which could mean modifications of the health goals for people living in closer proximity to the plant and recommended the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services also study potential risk of exposure through food.

The sign off by the science panel, which Science Advisory Board Chair Jamie Bartram called “an end point of some sort,” takes some ambiguity out of next steps in both Raleigh and Wilmington.

Last month, Rep. Ted Davis, R-New Hanover, said it was difficult for the state to move forward not knowing which level to use.

“That ruling, in my opinion, would have a great bearing on how we move forward,” Davis said, adding that he was glad to see the EPA taking an interest.

“I’m glad they’re coming here,” he said. “They need to be involved.”

Davis, who chairs the House Select Committee on North Carolina River Quality, said he has asked Speaker Tim Moore to extend the mandate of committee.

Last week, Davis expressed his frustration at Chemours for not scheduling a public forum in the Wilmington region.

In a letter to Gov. Roy Cooper, Davis asked the governor to revoke the plant’s permit if management continues to refuse to attend a forum in Wilmington “and shut them down until they can absolutely guarantee that they can operate without endangering the quality of our drinking water.”

On Thursday, the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, which operates the Wilmington region’s water system, said it would continue to push for more control over the sources of the of PFAS compounds.

“The report, as written and approved, does not immediately affect CFPUA operations as levels of GenX in finished water from the Sweeney Water Treatment Plant have been below 140 ppt for over one year,” according to a statement from the authority. “Levels of GenX in finished water from the Sweeney Plant have been below 140 ppt only due to source control efforts by North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ). Should NCDEQ no longer require source control measures at the Fayetteville Works site, however, our ability to ensure levels remain below 140 ppt would be limited because the Plant is currently unable to remove the compound.”