RALEIGH – Compromise legislation emerged from a monthslong back and forth between the House and Senate Thursday, but legal experts say that rather than dealing with GenX contamination, the new law could make it more difficult to enforce environmental laws.

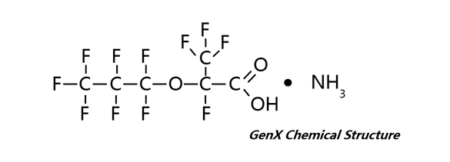

Tandem bills were filed in the House and Senate Thursday afternoon after leaders in both chambers signed off on new legislation to address per‑ and poly‑fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, such as GenX .

Supporter Spotlight

The bills specifically authorize the governor to “to require a facility to cease all operations and activities in the State that result in the production of a pollutant,” if the facility is found to have had unauthorized discharges of per and poly-fluoroalkyl substances and the situation meets a number of other specific criteria that appear to align closely with the state’s case against Chemours, whose Bladen County plant near Fayetteville is the source of of GenX discharges.

Robin Smith, a former state deputy environmental secretary who now runs an environmental consulting firm, told Coastal Review Online the way the law is drafted could muddy the waters in enforcement.

“Any time you have a brand-new provision like this that is completely disconnected from existing law so that you really can’t understand how it all works together, it’s going to raise a lot of questions about whether this was intended to be the way to go after sources of compounds like GenX, or whether it’s one more tool and how it will affect any existing enforcement actions.”

Either way, Smith said, the work of gathering data and building a case against a polluter is the same.

“The bottom line is there’s no magic bullet that lets you avoid the step of pulling together all the data that would show a connection between, for example, the air contamination and surface (water) and groundwater contamination or that show the connection between on the ground sources near Chemours and groundwater contamination,” she said. “That work has to be done and you have to do it at one point or another and there’s no magic order the governor can issue to avoid that step.”

Supporter Spotlight

Smith said the new process could lead to a longer shutdown process. Right now, the state can take its case against polluters directly to Superior Court, which DEQ and the Department of Justice did in Bladen County in response to Chemours.

Under the new law, any action would start in administrative court, but any ruling in administrative court could be appealed to the Superior Court and then move through the appeals process currently in place. That would not only add more time to reach a resolution, but require two sets of proceedings.

“You’ve got a better chance of resolving it at one go instead of having to go through two proceedings,” Smith said.

Earlier this year during discussion in the House River Quality Committee on legislation, Ted Davis R-New Hanover, told committee members that any new law requiring or authorizing a shutdown would be subject to the same kind of appeal process.

“It’s not just a simple process where you go into a plant and say ‘you’re shut down,’” Davis said at the March 24 meeting.

“I think it would be helpful to add language to explain how this kind of order fits in with DEQ’s normal enforcement,” she said. “Is this intended to be the only type of enforcement action in these situations or is it just another option.”

Smith said another part of the bill that overlaps with existing law is the establishment of procedures and responsibility for providing alternative water to private well owners whose wells are contaminated. State law already requires polluters to provide alternative water sources in the case of contaminated wells.

The new bill spells out new procedures and responsibilities and allocates $2 million to the Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Infrastructure to set up a fund to assist local governments with hookups to public water system. In a statement released after the bill was filed, its sponsors said that money would eventually be paid back by Chemours.

DEQ would also receive $1.3 million reallocated from an algaecide research project for Fall and Jordan lakes that was rejected last year by the Army Corps of Engineers. The money would go for new testing positions, reducing permitting backlogs, air sampling and analysis and sampling by the Division of Waste Management related to per‑ and poly‑fluoroalkyl substances. DEQ would also see another $479,736 to assist the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory in testing efforts and $537,000 to purchase a high-resolution mass spectrometer for emerging contaminant work.

The legislation includes $8 million funding to be distributed by the Collaboratory to set up statewide monitoring and testing for GenX and related substances.

The Department of Health and Human Services would get $530,839 to establish a new Water Health and Safety Unit in the Division of Public Health for the assessment of toxicity and impacts on human health from per‑ and poly‑fluoroalkyl substances.

Additional funding for both DEQ and DHHS has been one of the main disagreements between the House and Senate and has been a key priority for Gov. Roy Cooper, who last month proposed adding $14.5 million for GenX response and emerging contaminants testing in next year’s budget.

Cooper spokesperson Ford Porter said the administration is reviewing the legislation.

“DEQ is holding Chemours accountable and Governor Cooper proposed a strong plan to deal with emerging contaminants,” Porter said in a statement Thursday. “It’s shameful that it took legislative Republicans this long just to agree among themselves and that they appear only to be spurred by election year politics.”

The bills were filed in the Senate by Sens. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover, Bill Rabon, R-Brunswick and Wesley Meredith, R-Cumberland; and in the House by Reps. Davis, Holly Grange, R-New Hanover, Frank Iler, R-Brunswick and William Brisson, R-Bladen.

A joint statement from the sponsors released Thursday read: “We are pleased the House and Senate worked together to come up with a comprehensive plan that will help stop the pollution of our water supply, provide our families, neighbors and constituents access to clean, safe water and finally hold Chemours responsible for its pollution.

“This plan accomplishes our immediate goal of addressing water quality in southeastern North Carolina and puts the tools in place to help protect North Carolinians from GenX and other emerging compounds going forward.”

Reaction was swift from environmental groups who were critical of both the proposed changes to enforcement and channeling most funds through the collaboratory, a University of North Carolina Chapel Hill organization established in 2016. The research director for the organization is Jeff Warren, former science adviser for Senate leader Phil Berger, R-Rockingham.

Derb Carter, director the North Carolina offices of the Southern Environmental Law Center, said the legislature is still playing politics with a serious environmental concern.

“Rather than clarify or enhance state enforcement authority, this bill imposes multiple requirements on the Governor before he can order a facility that is potentially poisoning people to cease all polluting operations and activities — creating unnecessary hurdles to effective action. This is pointless given the Governor’s existing authority, and appears intended to protect the polluter, Chemours.

“It is unconscionable that the legislature would put politics above the safety of drinking water for thousands of North Carolina citizens.”

Carter said funding should have been focused on needs at DEQ rather than for more studies by the collaboratory.

Erin Carey, coastal coordinator for the North Carolina Sierra Club, said the bill could jeopardize DEQ’s progress so far in dealing with the contamination.

“Instead of giving the state better tools and adequate resources to address the problem, the bill may leave the state with weaker enforcement and a university-based research program that is disconnected from the needs of an underfunded state water quality program,” Carey said in a statement. “The outcome very well could be that we are in a worse place than we are today to deal with the problems.”