SUNSET BEACH – A developer applying for a state permit to build homes on oceanfront property at the west end of Sunset Beach has not provided sufficient documentation to validate he owns the land as required by law, according to the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Sunset Beach West LLC failed in its Aug. 7 application for a Coastal Area Management Act major permit to provide an authenticated property deed, said Geoff Gisler, a senior attorney at the nonprofit law center.

Supporter Spotlight

It is not the job of the N.C. Division of Coastal Management, the agency reviewing the application, to determine property ownership, according to an agency spokesperson.

“We don’t go hunting down deeds,” said Michele Walker, the division’s public information officer. “We can’t. It’s not our issue to decide. If you apply for a permit and you say you own the property we assume you own the property.”

According to state statute, an application must include a copy of the deed “or other instrument” claiming title to the property.

The April 9, 2014 general warranty deed for about 25 acres of land sprawling between the Bird Island Reserve boundary and the west end of Main Street states the that the document was “prepared without opinion of title,” according to Gisler.

“If you want to build something you have to own the property to do it,” he said. “In this instance the only documents that we are aware of that the applicant has submitted say that they don’t assert title. It’s entirely within their (the division’s) purview to check that an applicant claims title.”

Supporter Spotlight

Based on Brunswick County deeds for the property, the town, not the company, owns the land, he said. Records indicate that a company called Sunset Beach and Twin Lakes Inc. granted the property to Sunset Beach in 1987.

DCM could put a condition on the permit stating that the property has to be owned by the person developing the land before building may begin, Walker said.

“In any case, even if we don’t put the condition on the permit, our permit never gives you permission to work on property you don’t own. We might put the condition on there just as an extra, added step, but it’s not necessary,” she said.

Developer Sammy Varnum could not be reached for comment.

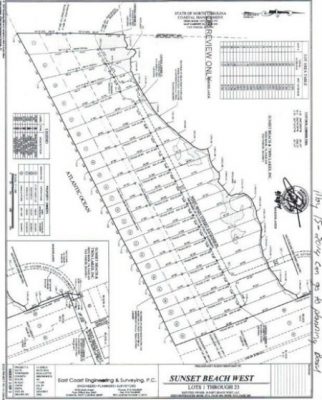

He’s proposing to build a 21-lot subdivision with a bulkhead along the west end beach where Mad Inlet once linked to the Atlantic. The inlet closed in the early 1990s, and the state’s Coastal Resources Commission voted last year to remove the old inlet from its inlet-hazard zone. That opened the land for development.

A private wooden bridge is also in the developer’s plans. The bridge is necessary to access the land from the end of West Main Street.

In order to build that bridge, the developer has to use the right-of-way at the street end.

The developer claims ownership of that right-of-way, which is about a town block. But, as with the case of the land, the developer has failed to authenticate ownership, Gisler said.

“As far as the ownership question, we have that question posed to our legal counsel,” explained Rawls Howard, Sunset Beach’s Planning and Inspections director.

The proposed subdivision has been a contentious topic in Sunset Beach, where opponents of the development have expressed concerns about environmental implications from building on the site and safety concerns because homes would sit where an inlet once existed.

The land falls within an “area of environmental concern” as well as a federal Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA (pronounced “cobra”) zone.

Building is not prohibited in these highly storm-prone zones, but government funding, including federal flood insurance and Federal Emergency Management Agency assistance, is restricted.

Public utilities such as water, sewer and electric that have received federal funds are prohibited from providing service to developments in CBRA zones.

This prompted the Brunswick County Commissioners earlier this year to rescind their 2014 plan to provide county water and sewer service to the proposed subdivision.

If the developer does authenticate ownership of land and the right-of-way, the board of commissioners must allow the public an opportunity to comment before commissioners authorize construction of the bridge. Commissioners must determine whether the bridge is in the public interest.

The developer has not received this approval – another reason the CAMA major permit application should be denied, Gisler said.

He points out this and a list of other reasons why the permit should be rejected in an Oct. 7 letter, written on behalf of the N.C. Coastal Federation, to coastal management officials.

In addition to the question of property ownership, the law center argues that the proposed development’s bridge, walkway and dock would significantly affect land protected under the coastal wetlands, estuarine shoreline, public trust and coastal shoreline areas of concern. Therefore, Gisler wrote, the project does not comply with CAMA use standards.

The proposed bridge, walkways and dock would shade more than 15,500 square feet of coastal wetlands, according to the letter.

“It is well-established that this type of shading has substantial adverse impacts,” Gisler wrote. “A study in South Carolina found that shading from docks resulted in a 71% decrease in Spartina alterniflora. Similar studies in Georgia have shown substantial thinning of salt marsh under docks, resulting in significant loss of biomass.”

He further argues that the project does not comply with the town’s CAMA land-use plan, which restricts uses in wetlands and freshwater marshes and requires new developments to connect to the county’s sewer system.

The developer plans to install septic systems.

“We hope the division of coastal management takes our comments seriously,” Gisler said. “If the state elects to issue a permit we will look very carefully at it and consult with the folks interested in this issue.”