Last of two parts

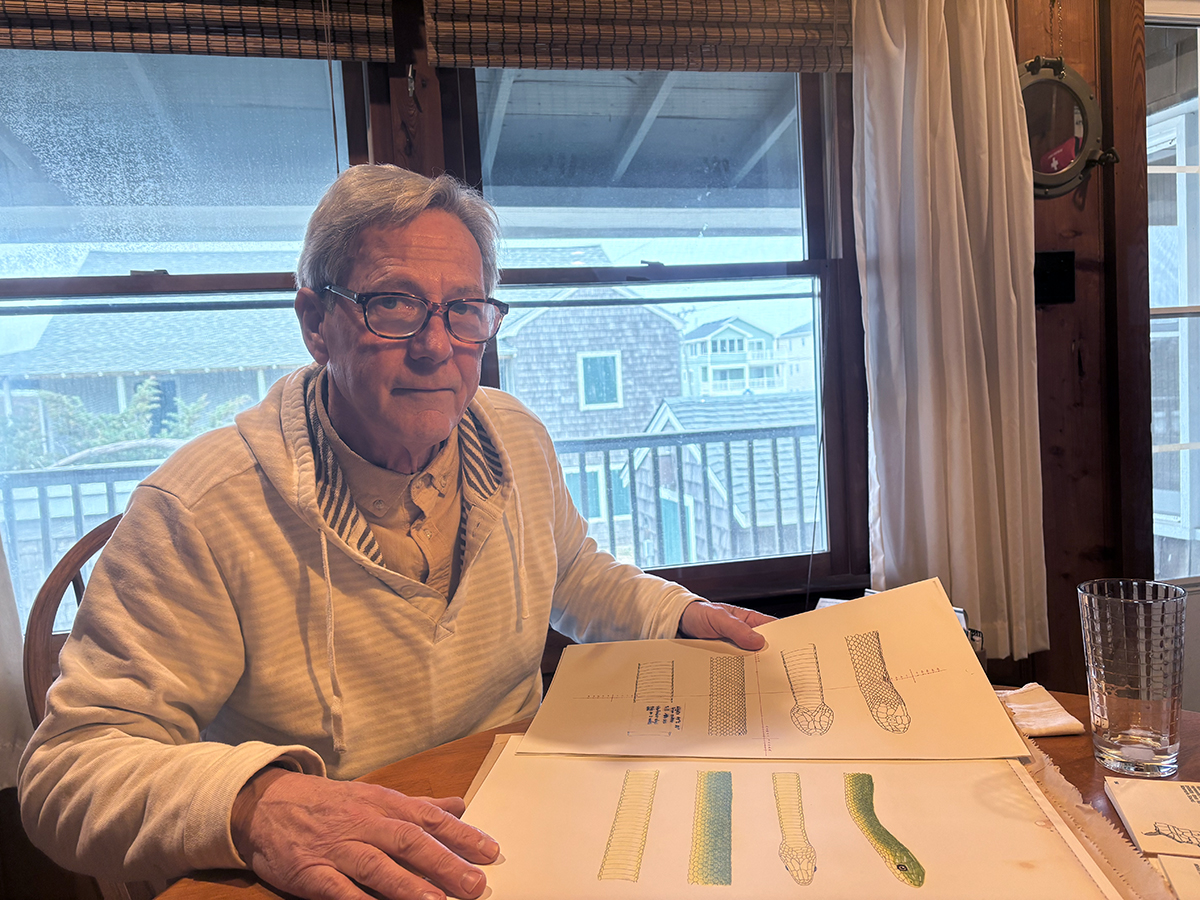

Bill Holman, left, and Ric Taylor stand in front of the old barn at Flyway Farms. Photo: Frank Tursi |

KNOTTS ISLAND – Ric Taylor came from Connecticut five years ago to look after the old house, which was showing its age and years of neglect. He’s still not sure why he didn’t get back in the car and go home after taking stock of the place.

Supporter Spotlight

“When I got here you couldn’t see the tennis court from here,” Taylor said from the front yard, pointing to the court about 100 feet away.

“You couldn’t even see the shoreline,” he continued, gesturing toward the North Landing River, which was a lot closer. “That’s how overgrown everything was.”

He stops and shakes his head at the memories, before turning around to face the grand, old house. “It was eaten up with termites, and people were walking into the house and taking stuff,” Taylor continued. “I must have been crazy to stay.”

This “island” – it’s really a peninsula – in a far-off corner of Currituck Sound has a way of beguiling folks. Maybe it’s the remoteness or the acres and acres of wide, open spaces. Maybe it’s the breathtaking view of the river and Back Bay or that nature in all its beauty and fickleness is always close by.

Taylor can’t explain in.

Supporter Spotlight

“But, I don’t know if I can leave now,” he said.

The Conservation Fund recently bought the house, the rambling barn and the 425 acres of Flyway Farms from Taylor’s in-laws, Ogden and Mary Reid, for $2.4 million. It was a bargain, noted Bill Holman, who directs the fund’s work in North Carolina. The property appraised for almost twice that amount, he said. The fund plans to sell most of the land to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which will add it to its Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge. The 8,300-acres of water and marsh account for almost two-thirds of Knotts Island. The fund plans to sell the house, barn and seven to 12 acres to a “conservation buyer,” Holman said.

The Corey Lodge was owned by William E. Corey, president of U. S. Steel, and was built around 1924 on Knotts Island. Corey built the 75-foot steel tower visible in the background to see poachers on his property. A fire destroyed the club in 1940. Photo: Knotts Island Scrapebook |

The Swan Island Club’s 38-foot power boat “Teal” is shown with club members and a harvest of ducks and geese in 1919. On a return trip from Currituck Courthouse on Nov. 12, 1925, the Teal struck a submerged piling and sank, the men were rescued by a passing schooner. Photo: Knotts Island Scrapebook |

“Acquiring this property has long been a goal of the Fish and Wildlife Service and conservation organizations,” he said. “We are very grateful to the Reid family for making it possible.”

Ogden Reid’s daddy, also named Ogden, wouldn’t have had a hard time explaining his affinity for the island and why he built the original house in 1920. The surrounding water and marshes at the time attracted what seemed like endless flocks of ducks and geese, making Currituck Sound one of the finest spots for waterfowl hunting in the world.

By the time the elder Reid arrived, duck hunting and Currituck were almost synonymous. Waterfowl had always been an important part of the region’s history. The very name, Currituck, is derived from an old Indian word for wild geese — Coratank. But the heyday for hunters probably started when old Currituck Inlet, near the Virginia line, closed in 1828. The shallow sound’s salinity dropped, its ecosystems changed and freshwater grasses soon covered its bottom. Ducks and geese followed in numbers that stagger the imagination.

This excerpt from the Southern Planter in 1857 gives us an idea. “Edgar Burroughs, farmer of Princess Anne, on Long Island, Back Bay, hires 20 men to kill waterfowl and deliver them to Norfolk. From the beginning of the season to December 30, 23 kegs of gunpowder and shot in proportion consumed. Waterfowl were brought to Norfolk once a week and piled up in the warehouse of Kemp and Bucky; 15 to 25 barrels were shipped each Wednesday to New York – highest shipped in one week – 31 barrels. Kinds shipped – canvasback, redhead, mallard, black duck, sprigtail (pintail), bullneck (ringnecked duck), baldpate, shoveler, etc., to which may be added a good proportion of wild geese.”

Waterfowl hunting for market became a leading occupation on the sound just after the Civil War and continued until 1918, when federal law made the sale of migratory waterfowl illegal.

By then, Currituck’s ducks were attracting a different breed of men. Starting in 1854 with the Currituck Shooting Club south of Corolla, rich and powerful Northerners built hunting clubs along the sound. Here’s a partial roster: George Gould, the son of Jay Gould, the tycoon who was said to own one of every 10 miles of railroad tracks in the United States; William E. Corey, president of U.S. Steel; George Eastman, the founder of Eastman-Kodak; the Proctors of Proctors & Gamble; the DuPonts; Joseph P. Knapp, publisher of the Ladies Home Journal; and George Hill, president of American Tobacco Co.

Flyway Farms sits on the banks of the North Landing River. That’s the house at the bottom of the photo and the barn at the top. Photo: The Conservation Fund Flyway Farms sits on the banks of the North Landing River. That’s the house at the bottom of the photo and the barn at the top. Photo: The Conservation Fund |

Al least 43 hunting clubs lined the shores of Back Bay and Currituck Sound in 1927, from the Sandbridge Club way up on North Bay in Virginia to the Dews Island Club south of Coinjock on the mainland in Currituck County. Some consisted of a house in the woods rented by a few friends, but many were sumptuous estates with household staffs, tennis courts and swimming pools.

Ogden Reid, the powerful publisher of the now-defunct New York Herald Tribune, employed as many as 22 people at his Flyway Club. They prepared and served meals, mowed the seven-acre lawn, tended the orchard of 900 peach trees, raised the 500 turkeys, milked the cows and acted as hunting guides for Reid and his guests.

For decades, Flyway and the other large hunt clubs were major employers in the sparsely populated region, providing steady jobs for local girls like Janet Simons. “My cousin (Beverley Dixon Rainey) and I worked with our other cousins, Linda and Butch Grimstead, during high school holidays at Flyway Club during the early 1960’s,” she wrote on an island web site. “My Uncle Harvey and Aunt Rosa were caretakers then. Beverley and I earned our first ‘real’ money: cleaning, cooking and helping with the Reid children. Daddy took Grandma Grimstead, Aunt Frances, Beverley and I (to) downtown Norfolk shopping. We each purchased a camel hair coat with a raccoon collar and brown high-heel shoes! We were ‘styling!’ Beverley later also went to New York during summers to work at the Reid’s home in New York.”

The household staff lived in the barn, which housed horses, cows and four automobiles on the ground floor and had 11 bedrooms and three baths on the second story. In its day, the barn was a splendid structure but since the Reids stopped coming regularly and the club’s fulltime caretaker died in the 1980s, the old building has been slowly falling down from the rafters.

“It’s a fixer-upper,” Holman admitted.

The great room in the house features exposed wooden beams and a rock fire place. Photo: Knotts Island Scrapebook |

Taylor has been doing his part, painting, plastering, replacing rotted boards. “I’m trying to remodel each of the bedrooms to what they could have looked like in the 1920s,” he said in a room with waterfowl prints on the newly painted walls and wooden decoys on the shelves. “It’s been slow, but we’re getting there.”

The house is in better shape. The original burned down on Christmas Eve in 1958. Nelson Rockefeller, then the governor of New York and a Reid family friend, sent his architect to Knotts Island to rebuild it according to original specifications. The house was completed in 1960.

We sat in plushy chairs in the house’s great room with its dark wooden exposed beams and giant rock fireplace. Family photos crowded the tables. Winston Churchill would have felt at home. The British prime minister visited Flyway in 1941 to persuade Reid to support American intervention in the war raging in Europe. Pearl Harbor a few months later made the argument moot.

Herbert Hoover, an old family, visited often to fish. Dwight Eisenhower came during his presidency in the 1950s.

“This is the last of the great family lodges,” Taylor said. “There is a lot of history here, and it’s coming back alive. But there’s still much to do.”