Knotts Island is really a peninsula that hangs from Virginia, top of photo, and separates North Landing River, bottom, from Back Bay. Most of the residents live on the east side of the peninsula. Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge, left, makes up two-thirds of the peninsula. The Currituck Banks stretch down the right side of the picture. Photo: Knotts Island Scrapebook

First of two parts

Sponsor Spotlight

KNOTTS ISLAND – It’s good to know that there are still some remote places left in North Carolina like this misnamed “island” in a far-off corner of our coast. It’s even better to know that someone cares enough to save a piece of it and the rich history that comes along with it.

But then, Bill Holman has always been that kind of guy. He has a long pedigree as a protector of North Carolina’s wild and beautiful places, starting more than 30 years ago when he was the first and only environmental lobbyist roaming the halls of the N.C. General Assembly. In those days, he might as well have walked around with a “Kick Me” sign pinned on his back. But Holman gradually wore down the hidebound men who dominated the legislature at the time, persuading them finally to repeal laws that prevented the state from passing environmental rules more stringent than their federal counterparts. Holman then watched with chagrin decades later as the current crop of lawmakers merrily undid his signature accomplishment. Talk about kicking a fella.

The Knotts Island ferry carries island children to school. Photo: NCDOT |

But by then Holman had long left the legislative business, but he didn’t abandon the state’s environment. He headed a state trust fund that provided money to buy ecologically sensitive lands. He took on the thankless task of leading North Carolina’s environmental agency – more thankless these days, I suspect, with federal prosecutors sniffing around — and now Holman directs the Conservation Fund’s work in the state.

That’s what brought him recently to the state ferry dock in Currituck on a bright but chilly winter’s day that hinted of snow. Founded in 1985, the Conservation Fund has protected more than seven million acres of America. Holman was heading across Currituck Sound to nail down the details of saving a few hundred more here in North Carolina.

Sponsor Spotlight

“We’re very happy to finally secure this property,” Holman told me a little later as the ferry pulled away from the dock on the start of its 45-minute trip across the sound. “The fund has been interested in this property for a long time.”

It announced in December that it had finally bought the 425 acres on Knotts Island, which is really a peninsula that hangs down from Virginia between North Landing River and Back Bay, the northern reaches of the sound. The ferry is the only way to get a car there from North Carolina without first driving it all the way up to Virginia Beach.

William Byrd |

The waterfront property that the fund bought has great ecological significance, but it’s the land’s connection to the history of this region that really drew me up here. For Flyway Farms, as the place is majestically called, is the last of the great hunting clubs of Currituck. The farm is one of the few reminders of the days when great wealth and seemingly endless flocks of ducks and geese made the marshes and waterways of this remote part of the state the exclusive playground of the rich and mighty. Great captains of industry and princes of finance had lodges along the sound. Presidents and prime ministers often joined them. The region had such a gilded reputation that the train that carried the potentates south from Norfolk was called the Millionaire Special.

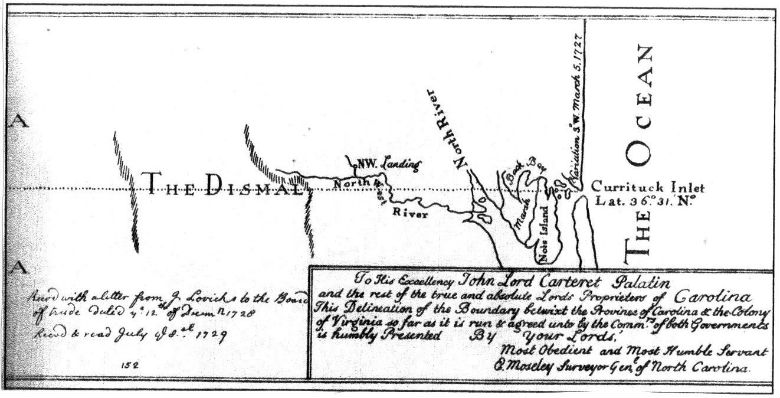

William Byrd may have been the first of the breed to come this way. A Virginia aristocrat and politician, Byrd apparently enjoyed looking down his long nose at his lesser neighbors in North Carolina. He came to mind as the ferry slowly steamed past duck blinds and around the notorious shoals that so bedeviled Byrd and his pilot in 1728. He had been assigned the job of helping survey the disputed boundary between the two colonies. Byrd later wrote about the experience in what is now a famous book, Histories of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina. In it, Byrd makes great sport of poking fun at the rubes he encounters, but the book is formal and rather staid compared to the “Secret History,” which Byrd compiled on the spot and had intended just for friends. In it, he tells us what he really thinks.

“This Navigation was so difficult by reason of the perpetual Shoals, that we were often fast aground,” Byrd wrote of his Currituck crossing. “Our Pilot wou’d have been a miserable Man if One half of that Gentleman’s Curses had taken effect.”

Byrd and his cussing companion finally made it to Knotts Island. After slogging ashore through knee-deep mud, they waited in a farmhouse for the surveyors. Word of their arrival spread through the sparsely settled country, and a small crowd slowly gathered to catch a glimpse of the distinguished visitors.

“Amongst other Spectators came 2 Girls to see us, one of which was very handsome, & the other very willing,” Byrd wrote. “However we only saluted them, & if we committed any Sin at all, it was only in our Hearts. Capt White, a Grandee of Nott’s Island, & Mr. Moss, a Grandee of Princess Ann, made us a visit & helpt to empty our Liquor.”

This is one of the sketches William Byrd’s surveying party did of the boundary between North Carolina and Virginia. Notice the peninsula that’s labeled “Nots Island.” Source: Histories of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina

Alas, no booze or babes awaited Holman and me when we arrived on the island. We were greeted by long stretches of two-lane blacktop that coursed past farm fields and modest homes with boats in the front yards, past the small Methodist Church, past the volunteer fire department and the island’s only grocery store.

We took a left on the aptly named Marsh Causeway and entered another world. The seven-mile-long peninsula is really two places. Most of its 2,000 or so residents live on a thin strip of high ground along the east side of the peninsula. Ducks, geese and swans have the rest of it.

Almost two-thirds of the peninsula is within the 8,300-acre Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge. Much of it is open water and marsh, now wearing its amber winter coat and stretching to the horizon on both sides of the causeway, the main road through the refuge.

This land has its own colorful history after the Mackie family started acquiring it in 1716. One of its later owners, Thomas Dixon Jr., grew up on a farm near Shelby, in the state’s foothills, during the Reconstruction. He became a Baptist preacher and a prolific author whose writings glorified the antebellum South; white supremacists are still fond of quoting him. Director D.W. Griffith turned Dixon’s novel and play The Clansmen into “Birth of a Nation,” a 1915 silent film that is considered a ground-breaking technical achievement that launched modern filmmaking but is so disgustingly racist that it’s impossible to find on Netflix.

Joseph Knapp feeds pheasants at his house on Knotts Island. Photo: Knotts Island Scrapebook |

Joseph P. Knapp, who bought the land from Dixon, was less notorious and more helpful to the ducks and geese. The Brooklyn, N.Y., native fell in love with the marshes and the birds of Knotts Island. A publisher and philanthropist, JP, as he was called, built a palatial estate here and experimented with various techniques to better manage waterfowl. It was on the island, says local folklore, that he started what is now Ducks Unlimited. JP was 86 in 1951 when he died in his sleep in his Manhattan apartment. More than 400 people attended the funeral. He left instructions for his body to carried to little Myock, just across the sound, so that he could be buried near his island home.

The Mackay land changed hands several times after Knapp’s death before the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service bought it in 1960 to establish the refuge.

Holman and I pulled off on one of the few wide spots along Marsh Causeway and into a gravel lot. It was empty except for a black Harley Davidson in the corner. A small, elevated boardwalk extended over the marsh. The scenic stop is part of the Charles Kuralt Trail, a self-guided auto tour that snakes through the coastal refuges of North Carolina and southeastern Virginia. It was named to honor our state’s most famous traveler, who wore out six motorhomes taking a generation of TV viewers to the backwaters of America. It was only after Kuralt’s death in 1997 that we learned just how far he wandered off the trail.

“This is a good place to take a look at the refuge and where our property boundaries are,” Holman said as we walked up the boardwalk. “And it’s a pretty day.”

The boardwalk overlooked a portion of Back Bay. Duck blinds dotted the water like little brown islands. Decoys bobbed in front of several.

“They’re wasting their time,” the man in the black motorcycle chaps said as he peered through binoculars toward the hunters. “It’s too nice of a day. Cold and snow tomorrow. That’s when I plan to be out there. The hunting will be better.”

The owner of the Harley turned out to be a local guy, born and raised just across the state line. He comes often to Knotts Islands to hunt, fish or peer through binoculars at those who are. He was happy to hear that Holman’s outfit has bought old Flyway Farms.

“This place is special,” he said. “It needs to stay that way. It doesn’t need subdivisions and shopping malls. You can go anywhere for those.”

Tuesday: Flyway Farms and the hunting clubs of Currituck