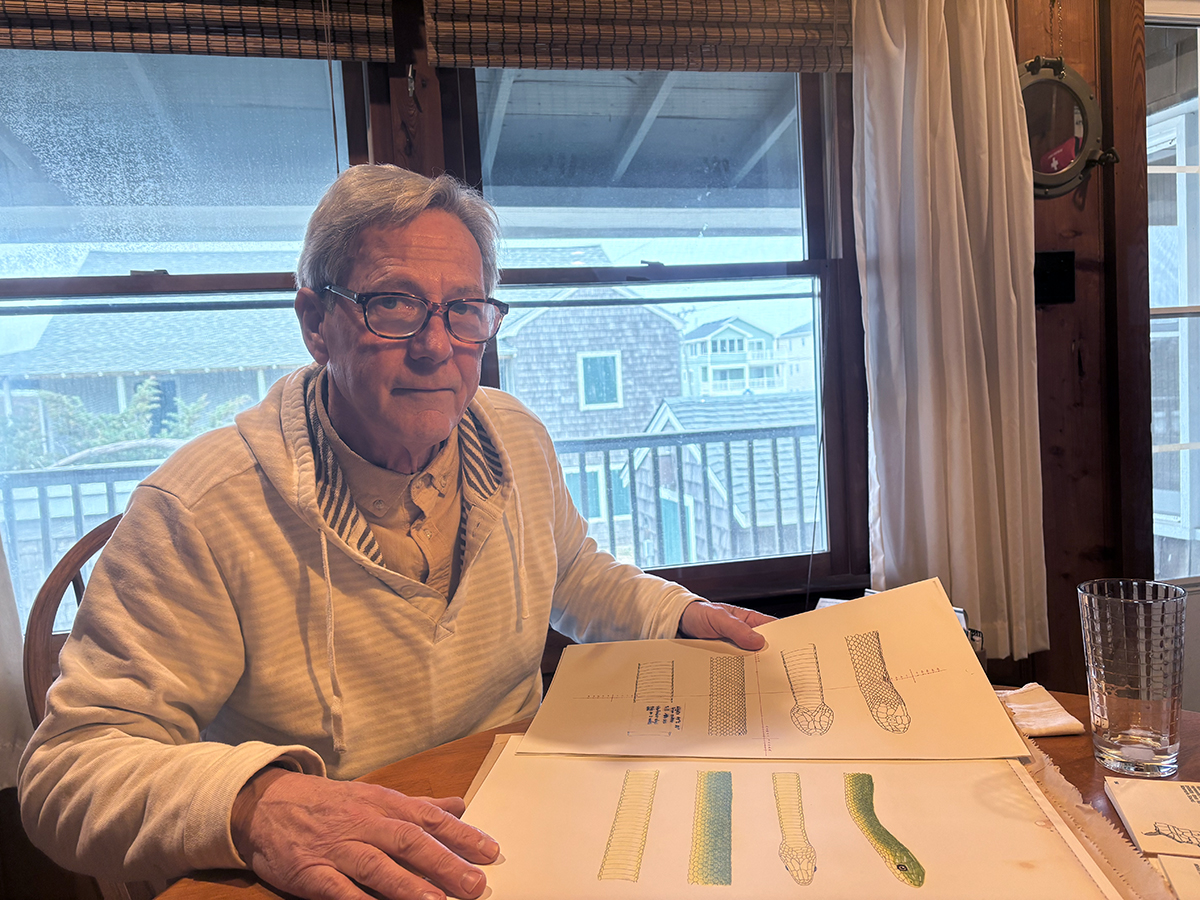

A younger Sam Bland shows off his gigging prowess. Photo: Sam Bland |

Autumn along the coast is a time of transition and movement. The cycle of nature is turning with endings and new beginnings. Birds and butterflies are migrating in the air while the fish are moving in the sea.

During their migration peak in late October and early November, summer flounder are swimming out of the barrier island inlets, heading for the continental shelf where they will spawn. As they make their way through the estuaries, they are pursued by recreational fishermen lining the inlet beaches with their rods cradled in a holder firmly anchored in the sand. Other fishermen sling their bait from a boat and drift along the channels during an incoming tide. People even go out at night wading through the water to catch flounder using a method known as gigging.

Supporter Spotlight

Even though flounder gigging is a somewhat unconventional way of fishing today, it has been a method to harvest fish at night for thousands of years. Native Americans would use the naturally flammable pine fatwood, also called lighter wood, to make torches that would push away the darkness and bring light to the crystal clear waters. They would wade in the shallow waters with a sapling spear armed at the end with the telson, or tail spike, of a horseshoe crab, to impale the flatfish.

Later, people started using bamboo poles packed with coal, then kerosene lanterns as the light source and spear points started being made out of metal.

Today flounder gigging boats are set up with glowing lights powered with generators or deep cycle batteries that give the appearance of a UFO slowly hovering around the marsh. The illumination is so bright that aircraft might mistake it for runway lights at an airport.

As a young college student in the late 1970’s, I was invited to go flounder gigging one evening by my boss. I was working part-time and I thought this would be a good opportunity for me to bond with my supervisor since I would be soon be applying for a full time job. I had heard of frog gigging before, but never flounder gigging, so I was intrigued to find out how you go into the water at night and catch flounder without a fishing pole.

Before we went gigging that first night, we had to prepare our gear. We took an old galvanized wash tub and inserted it into the center of an inflated tire inner tube. Then a full size truck battery was put in the tub and a rope was attached to the tub handle. This would be our source of floating electrical power. Next we ran some electrical wire through a four foot piece of threaded lead pipe and attached an exterior porch light fixture (the type with the thick glass globe) to one end of the pipe. On the other end, the wire extended about ten feet out of the pipe and alligator clips were attached to the wire. Now we had our light source.

Supporter Spotlight

We then found a couple of old brooms and cut the handle off and attached steel gig heads to one end. Armed with our spears, we strapped on waders and stepped into the cool waters of the sound in search of flounder.

Masters of camouflage, flounder aren’t easy to spot buried just beneath the surface of the sand. These, however, weren’t so lucky. Photo: Sam Bland |

The alligator clips created sparks when they came in contact with the battery terminals and the harsh glow of the light surrounded us and reached into the water. It soon became apparent that I was asked to tag along to drag the wash tub with the battery. Even though it floated, you still had to pull it along. I also carried the light, which produced a jarring shock through the pipe every time a little water splashed onto the battery terminals. This provided much amusement to my boss. I didn’t care though since I was fascinated with all the creatures moving about; there were hermit crabs, jellyfish, skates, whelks, stingrays, needle nose gars, stargazers, mullet, puppy drum and small sharks.

My boss had been flounder gigging since he was a child and passed on to me the secrets of finding these fish which are masters of camouflage. A flounder will bury itself just beneath the surface of the sand with only its eyes exposed. Both eyes are exposed since a summer flounder has both eyes on the left side of its body. As larvae, their eyes start out on both sides of their head and gradually move to the left side of their head. These fish can also change the color and the spot pattern of their skin on the exposed side of their body. Once these fish are embedded into the sand and change their color to match the surrounding environment they are extremely hard to see. This is a perfect combination for the flatfish to explode from their concealment to ambush prey such as shrimp or minnows.

Once I learned what to look for in locating a flounder, I thought this would be easy. But I must admit that I gigged plenty of flounder shaped piles of sand before I could spot the eyes and outline of their mouth that resulted in stocking my freezer with fish.

One still fall night, I was out looking for some flounder to gig along the calm waters of Beaufort Inlet. I anointed myself with the outdoorsman cologne of choice, Deep Woods Off, to keep the no-see-ums or flying teeth at bay and readied my gear to catch some flounder. I had since upgraded to a self-contained backpack rig that allowed me to carry a small lawn mower battery on my back freeing my hands to hold a light in one hand and a gig in the other. I began near the ocean side and worked my way back toward the sound. Along the way, I picked up a number of nice fat flatfish, one was over two feet long and I was already planning the menu to bake that monster.

With my head down, I continued to slowly shuffle along the shallows intently peering into the clear water to find the tell-tale shape of a flounder with two eyes peeking out of the sand. Then, all of a sudden, my concentration and nerves were destroyed when a man’s booming voice called out from the heavens, “my land son, what are you doing”? His exasperated voice was thick with the distinctive Old English inflection passed down from the early English settlers that made a tough living fishing the waters surrounding isolated islands such as Ocracoke and Harkers. This unique dialect is referred to by some as a high tider or “hoi toider” accent.

This familiar Down East brogue inflection of the voice made me think that if God was from Harkers Island, that must be what his voice would sound like. I was born in Carteret County and lived in the county most of my life; so, I am familiar with the Down East dialect. I know what a dingbatter and dit dot is and I have been mommicked many times in my life.

Startled by the voice, I then looked straight ahead to see that I was about to walk headlong into the bow of a large shrimp boat that was beached perpendicular to the shore. I looked up and saw the shadowy figure of a man hovering above me on the bow of the boat.

“Flounder gigging,” I slowly replied, almost like I was asking a question.

He said, “Son, you’re just out here getting in somebody’s way that’s trying to make a living.”

I replied without a word by smugly hoisting up my huge flounder with my chest stuck out like a rooster.

With a shrug, he dismissed my catch by saying “frying size.” You could hear the air leave my chest as it deflated.

|

|

The three stages of “cam”, or calm, from the top: cam; “sic,” or slick, cam; and “dea.” or dead, sicam. Photos: Sam Bland |

I asked if he had run out of gas and he seemed insulted that I would suggest that a man of the sea would make such a foolish mistake. He said that the boat had “lost its wheel” and made no attempt to provide an interpretation to address my obvious confusion.

As I made my way around the bow of the boat I attempted some small talk and said, “It sure is calm tonight.”

To which the shrimper man replied, “Son, you don’t know cam.”

Using the bow of his boat as a pulpit, the shrimper then began to preach the three virtues of “cam”, or calm, as it lies on the water.

“Cam”, he explained, is when there are no whitecaps or waves, but the water surface will still show a few ripples from a light wind. A “sic cam”, or slick calm, he proclaimed, is developed when the ripples are gone and the surface is becoming slick, but the slickness is not completely uniform. He then finished off the trinity with the holy grail of calm, the “dea sic cam”, or dead slick calm. This is when the surface is so slick that it looks like polished glass, that everything that meets the water has a mirror image and that the surface is so still that you can’t even determine the direction of the current.

I stood there in a trance, visualizing the degrees of calm, then I looked up to the bow of the boat and the shadowy figure had retreated into the recesses of the boat.

The next morning I returned to where the boat was beached to see if the shrimper needed any help. Knowing that those who work on the water are self-reliant, I wasn’t surprised to see that the boat was gone.

Since that night, every time I head out to go flounder gigging I continue to grade the stillness of the water as calm, slick calm or dead slick calm.