Second installment of a two-part series special to Coastal Review

My mullet-fishing experience began in Carteret County, over half a century ago, but over the subsequent years and many scientific expeditions to find fossils, we have continued to cross paths with our “jumpin’ mullet,” catching them in places as far-flung as Hawaii and seeing them in markets of Europe, Africa, and Madagascar.

Supporter Spotlight

We have long marveled that our local tradition for drying mullet roe, which goes back many generations in my wife Lida Pigott’s family, somehow has its roots on the Mediterranean Island of Sardinia, the source of “Cabras gold,” the prized bottarga di muggine of Italian cuisine.

On my first visit to this enchanted island, just off the coast of Italy and second only to Sicily in size in the Mediterranean, I presented a talk at an international meeting of paleontologists and archaeologists on the topic of “Early Man in Island Environments,” featuring my years of work studying prehistoric Madagascar. I was fully captivated by the mysterious Sardinian landscapes, with more than 7,000 ancient ruins from the Neolithic and Bronze Age, some as old as Stonehenge and the pyramids.

I told myself I had to get back to Sardinia one day with more time to absorb it. I knew Lida would love this place because it is so strange and at once familiar. That was 1988.

We finally got back there a few months ago, for a nice long stay, and one of our projects was to explore the very heartland of one of Italian cuisine’s most famous products, bottarga di muggine, our own beloved mullet roe.

The wonderful archaeological museums and sites on the island tell the story well. Big estuaries with hydrology and scale similar to our own Core Sound, known locally as stagno (ponds), have been exploited for mullet seasonally, just as here in coastal NC or Hawaii or hundreds of other places in all the warm oceans of the world.

Supporter Spotlight

Mullet have undoubtedly fed Sardinians steadily for 5,000 years or more, from the indigenous Nuragic culture, through successive colonization by the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Spaniards, and medieval feudal lords.

In fact, one of the last vestiges of feudalism as an economic strategy anywhere in Europe was the mullet fishery of famous bottarga producers like the Stagno di Mar `e Pontis, near Cabras, Sardinia.

By the mid-1900s this ancient lucrative industry, still owned by what today might be described as an “oligarch,” was regulated through eight levels of bureaucracy, whereby so many folks with fancy titles and allegiance to the “owner” got such large cuts that sometimes not much was left for the fishermen who did the catching.

Long-standing issues flared up regarding the maintenance of the canals to the ocean that have regulated the water flow for centuries, even millennia. Poaching was rampant. The fishery was in a poor state.

Something had to be done, and some violence came with the transition, as fishermen’s consortiums, government officials, and local business interests tried to set things right in a variety of sometimes conflicting ways.

In an infamous 1978 crime incident, the feudal overlord, Don Efisio Carta, was kidnapped by banditi and never found, although a ransom was collected.

By the 1980s, the now outlawed feudal hierarchy had been replaced by a consortium of fishermen’s cooperatives, and to this day they run a thriving fishery based primarily on the mullet and bottarga but also with eel and tuna fisheries, shellfish farming, and other maritime industries to sustain the large work force through the off-season for the migratory mullet.

Over several weeks, Lida and I had been eating seafood, especially targeting bottarga dishes, all over Italy and Sardinia. We were especially excited to arrive in the absolute world capital of the jumpin’ mullet and the bottarga industry, Cabras, for a few days of culinary “mullet research.”

We visited the splendid local museums, but as mullet fishermen ourselves we were just as interested to see where the fishermen store their nets and dock their boats, what kinds of tackle they are using, and what they are generally about.

We were amazed to discover that the Cabras cooperative uses a single type of molded fiberglass skiff, a stout outboard motor of a single brand, and nets nearly all alike in tidy labeled bins and net bags.

As net hangers ourselves, we were impressed that their tackle and techniques looked almost exactly like ours, down to the corks and knots.

The folks at a local store selling bottarga and smoked mullet insisted that, with our interest in the subject, we really had to visit the museum dedicated to the history of the local fishing culture, just down the road a bit.

We walked there along a causeway through the vast wetlands to reach the cluster of buildings on a high place out in the marsh, beside a deep channel leading out into the stagno.

Part of the “fish tourism” project of the Cabras fishermen’s consortium, Mar’e Pontis Museum had a sweet friendly charm that reminded me of our own Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island.

The site also hosts a great restaurant, featuring local seafood, and an ancient chapel where the fishermen have prayed for safe and productive fishing for almost a thousand years.

From Pinuccio Carrus, a mullet fisherman who also guides museum tours, we learned about the boats, fishing gear, and thousands of years of fishing and fishing culture on this spot.

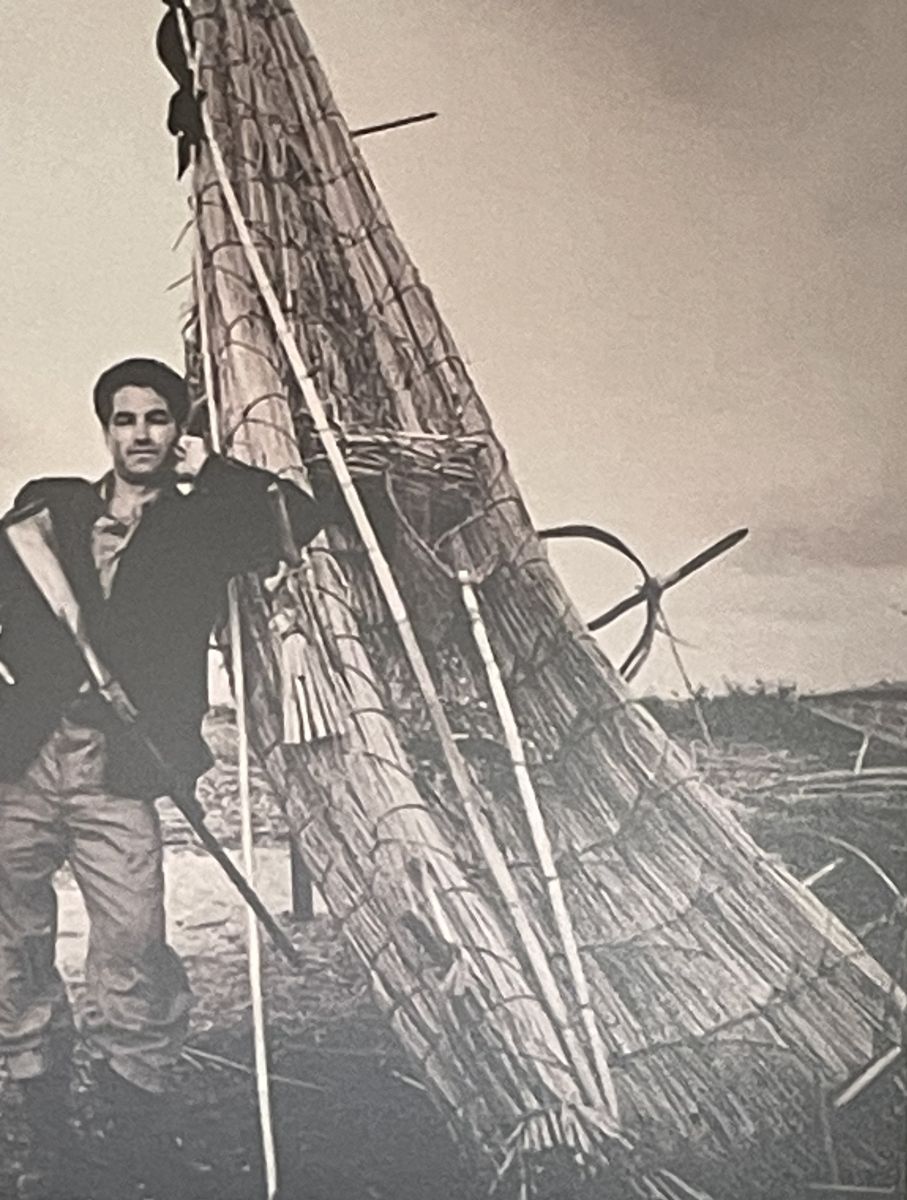

Probably since the Neolithic, fishermen here used small agile boats made entirely of reeds from the marsh, and some still do.

Wooden rowboats from years past, shaped like large high-ended canoes, similar to the gondolas of Venice, are now mostly rotting in yards, with molded fiberglass being the material of choice for most commercial fishing in the stagno today.

The museum had all kinds of nets and traps, for mullet and eels primarily, including ones that looked like our pound nets and gill nets.

Today, the fishermen use monofilament gill nets almost identical to ours in North Carolina, although the spear-fishing from reed boats is still practiced, too, much as it has been since prehistoric times.

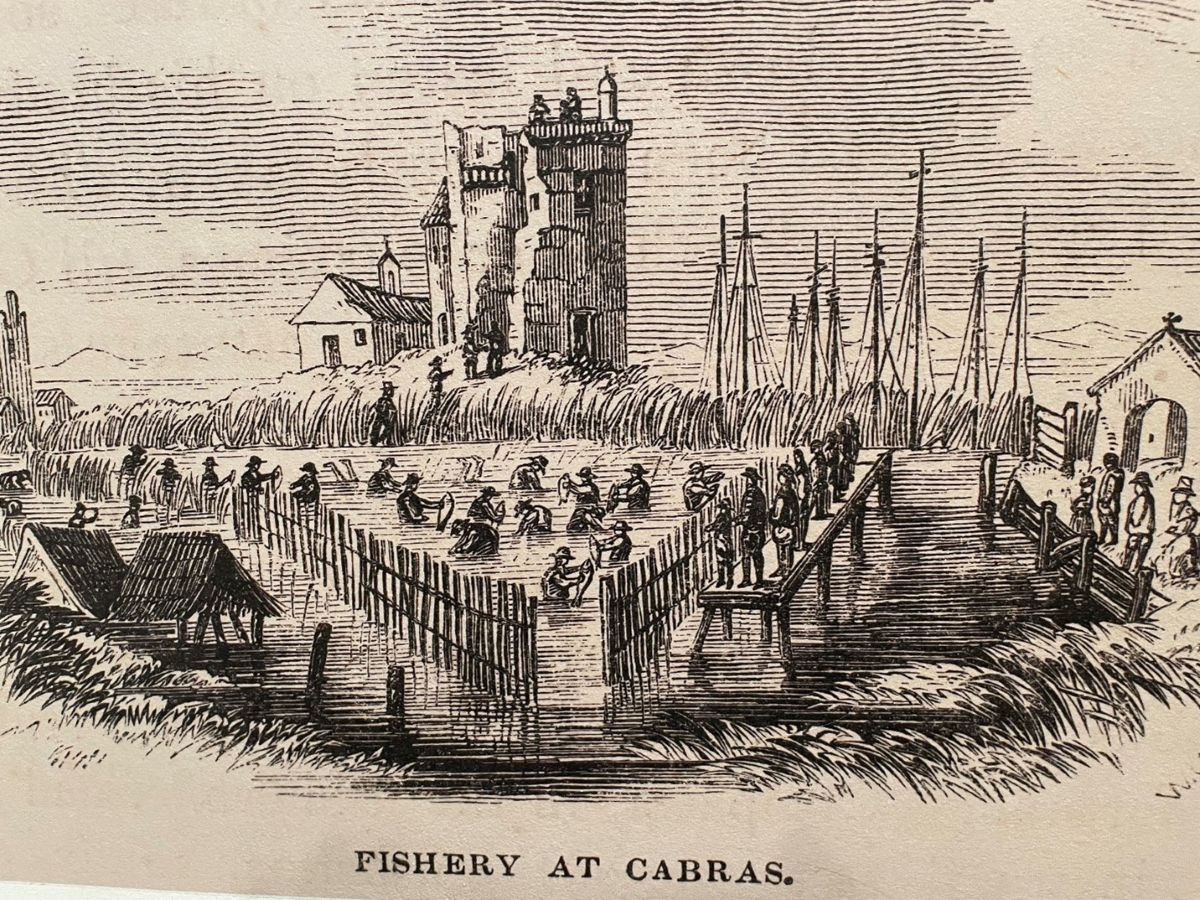

Drawings and photos of fishing activity during the heyday of the feudal fishery show pound nets and fish corrals full of mullet with fishermen standing in their midst, taking them out by hand.

Having done a bit of that myself, I couldn’t help wondering if they had to watch out for stingrays lurking on the bottom of the mass of hemmed-in fish the way we do!

Of all the mullet-based meals of the trip – and there were many all over Italy and Sardinia – one of the most memorable was at the Restaurante de Madre de Rosy Circu in the heart of Cabras, at a junction of several of its ancient labyrinthine streets.

It was the only time anywhere that we dined on an entirely mullet-based pizza. It had a thin crust, a tomato and parsley sauce, and a topping of smoked mullet, sprinkled liberally with ground mullet roe (bottarga), a kind of double-mullet treat!

Another favorite we had several times around the island was a type of thick, rectangular local pasta with tiny clams (vongole veraci) and loads of ground bottarga. One of the best dishes was purple artichokes smothered in thin amber slices of bottarga, a feast for both the eye and palate.

Local shops sold a wonderful pâté made from bottarga and just right for any imaginable cracker.

The mullet fishery of Sardinia, although today only a small fraction of the historical fishery, seems to be doing fairly well. The industry in value-added fish products from local mullet, eel, and tuna seems to be thriving.

One change is that whereas relatively cheap U.S. mullet roe used to be imported salted or frozen to Italian factories for conversion to preciously expensive bottarga (not quite as expensive as caviar, but in that league), fish industries from Carteret County, to Manatee County, Florida (Cortez area) have sprung up that convert local mullet roe to a quality bottarga that sells on the internet for prices similar to the celebrated Sardinian stuff.

Combined with beach tourism and the draw from internationally unique 3,000-year-old giant stone statues (I Giganti di Mont’e Prama), folks there on the Sinis Peninsula seem to make a pretty good living by the stagno.

The mullet still come in large numbers from the sea every year, swelling the estuaries and feeding the people, dolphins, and birdlife, then returning to deeper water to complete their life cycle. Just like back home here in Carteret County, and virtually all the warm coastal waters of the globe.

Our mullet is a fish for the world, a true cosmopolitan. I’m glad to have made its acquaintance in so many wonderful places.