First of two parts.

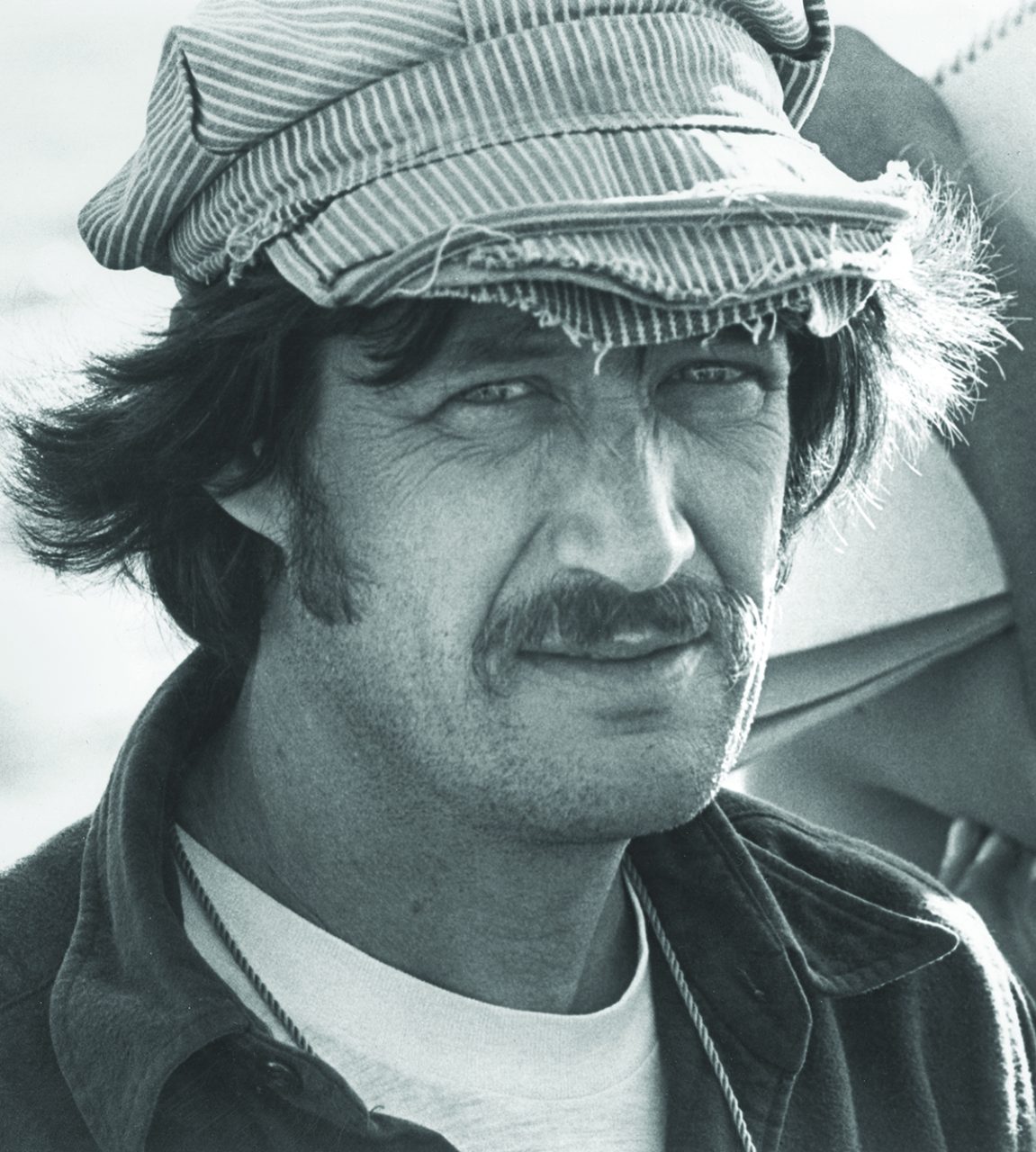

It was a nasty January day about 14 years ago, not long after publication of his book, “The Battle for North Carolina’s Coast: Evolutionary History, Present Crisis, and Vision for the Future,” when veteran East Carolina University coastal scientist Dr. Stan Riggs, the book’s lead author, had an unexpected and impactful visit. Not only did it prolong the sunset of his then-50-yearlong career, it cemented the reach of his legacy beyond academia to the lives of everyday people.

Supporter Spotlight

And it inspired Riggs to write 10 reader-friendly books focused on a blend of science, culture and history of North Carolina’s northeast and central coastal region.

Related: Riggs to launch first book in series Sunday on Harkers Island

“I’ve done a lot of work here, but science builds on itself,” he said. “And so, I just decided in 2018 that they could just put me in the ground, and who would care? Who would know what I’ve learned?”

In October, the first volume in the series, “Cape Lookout National Seashore, Paradigm for a Coastal System Ethic,” was released. Subsequent volumes, several of which are already written, will cover North Carolinas Inner Banks, or inland coastal region, Outer Banks and the continental shelf.

The books, all planned for release over the next three years, present Riggs’ coastal science research in accessible and understandable language, accompanied by striking photographs and graphics that seek to educate, enrich and engage readers.

Supporter Spotlight

Also, the ecotourism-centered program called North Carolina Land of Water that was first proposed in the book, “The Battle for North Carolina’s Coast,” has been transformed from a dim concept into its current sunbeam of possibilities. All because of the support offered to him on that blustery day.

“A nor’easter was blowing Billy out there — it was cold!,” Riggs, 87, recalled in a recent interview with Coastal Review. “I got a knock on the door, and two people were standing there. They introduced themselves and asked if we would take them out on a field trip. And I said, ‘You don’t want to go out there today.’”

But they insisted on a tour of the region he and his co-authors had written about in the book. They wanted to see it for themselves, and chat with some of the folks who lived there. Intrigued, and convinced his visitors were serious, Riggs made some quick phone calls, and soon they were all piling into a vehicle and hitting the road.

“We had one hell of a good trip,” Riggs recalled about the four-day adventure. Starting in Greenville, the group wound their way through the Albemarle Penisula and Inner Banks counties, along rivers, through the wildlife refuges, and down the Outer Banks to Ocracoke Island, then on to a ferry to the Core Banks. Some year-round residents shared “incredible” meals, he said, and invited them to stay.

“We covered the whole system,” Riggs said, a tinge of amazement still in his voice. Finally, as everyone said their goodbyes, one man got out of the car and walked over to Riggs.

“He put his arm around my shoulder, and he said, ‘The real reason we’re here is we’re going to give you some money.’

Surprised, Riggs responded: “‘I don’t need money.’ He said, ‘Yes, you do.’ I said, ‘Why?’”

“‘We want you to implement the vision that you set out in your book,’” Riggs recalled. “And that was the beginning of NCLOW.”

After the visit, representatives from the Kenan Institute for Engineering, Technology and Science at North Carolina State University provided funding for Riggs to create the North Carolina Land of Water, or NCLOW. The nonprofit is “dedicated to advancing coastal science, education, and community stewardship through research, outreach, and partnerships,” while working to ensure that the state’s coastal systems are “understood and safeguarded,” according to a press release.

In October, NCLOW announced the appointment of Stanton Blakeslee to its board of directors to guide the nonprofit’s future projects and fundraising. As noted in the release, the appointment “comes at a critical inflection point for the organization,” and his leadership will encourage “strategic investment and cross-sector innovation.”

Blakeslee, 55, who had attended ECU and worked for the N.C. Literary Review, is currently the president and CEO of Instigator Inc., a Greenville-based life science marketing firm. His experience includes investment in real estate development and consumer goods industries, and he serves as a member of the East Carolina Angels, an angel investment network.

So far, he has helped Riggs divide his approach to NCLOW in two phases, Blakeslee said.

“Phase one culminated with the development of the books,” he said. “It was a way for Stan to formalize not only his life’s work, but what he sees as a sustainable future for the coast.”

Blakeslee’s background as an entrepreneur who understands private equity and venture capital as well as conservation work provides insight into the goals of NCLOW, he explained.

“So the more I started to hear about what he was envisioning, I was like, ‘Oh, wow. So there’s like an economic concept behind everything that you’re trying to do here.’ We’re not trying to stay off the coast. What we’re saying is let’s look at where the opportunities are and invest … so we can sustain this resource for everyone.”

Riggs’ earlier work with the Bertie County and Scuppernong River projects are two big success stories that drive NCLOW’s future initiatives, Blakeslee added. By harnessing creative ideas to manage and maintain the natural resources, a community’s economy and sustainability can benefit. For example, Windsor, Bertie’s county seat, mitigated flooding risk by requesting the water in a river dam be released slowly about a week before a predicted storm. And the community constructed tree houses above the river’s edge to rent, which quickly became a popular ecotourism attraction.

“The geographic setting of Bertie County provides a prime basis to capitalize on the incredible water system it has been blessed with,” Riggs wrote in his 2018 report, “From Rivers to Sounds in the Bertie Water Crescent” that proposed an approach to ecotourism and environmental education. “Consequently, NCLOW recommends developing a series of five educational and recreational ‘water hubs’ for ecotourism development.”

NCLOW can serve as a catalyst for other communities to take active steps towards sustainability, Blakeslee said. It’s a matter of determining the challenges, how to address them, and how to transform them into economic opportunities.

“I think Stan proved a lot of that in its first 10 years,” he said. “And now we’re looking at what the next 10 years, and possibly 20 years, looks like.”

Over his long career, Riggs, professor emeritus at ECU, has authored or co-authored 16 books and more than 100 journal articles. But data-heavy research terminology and scientific jargon is a heavy lift for nonscientist readers, Riggs noted, and he believes that educating people about the science in their lives is a critical responsibility so people can understand the processes and relevant public policies that affect their lives.

“You know, when I was at the university, I got all my salary and everything was public funds, and all my research came from public organizations,” he said. “And so I see this as a give-back. It’s one thing to go out there and do a project and raise money and write your technical papers. But nobody in the public domain will ever, ever, read a technical paper.”

Riggs said he decided to write the Cape Lookout book because it is a success story. The undeveloped barrier island showcases how natural beaches recover, adapt and rebuilt after storms because over wash and other coastal processes are not blocked by infrastructure.

With an affable, every-man persona and an uncanny ability to recite minutia about ancient and ongoing geologic processes at seemingly every location he encounters, Riggs has spent considerable time traveling throughout the coastal region talking to residents and politicians in small communities, many of which are stressed by poverty, job losses and frequent flooding.

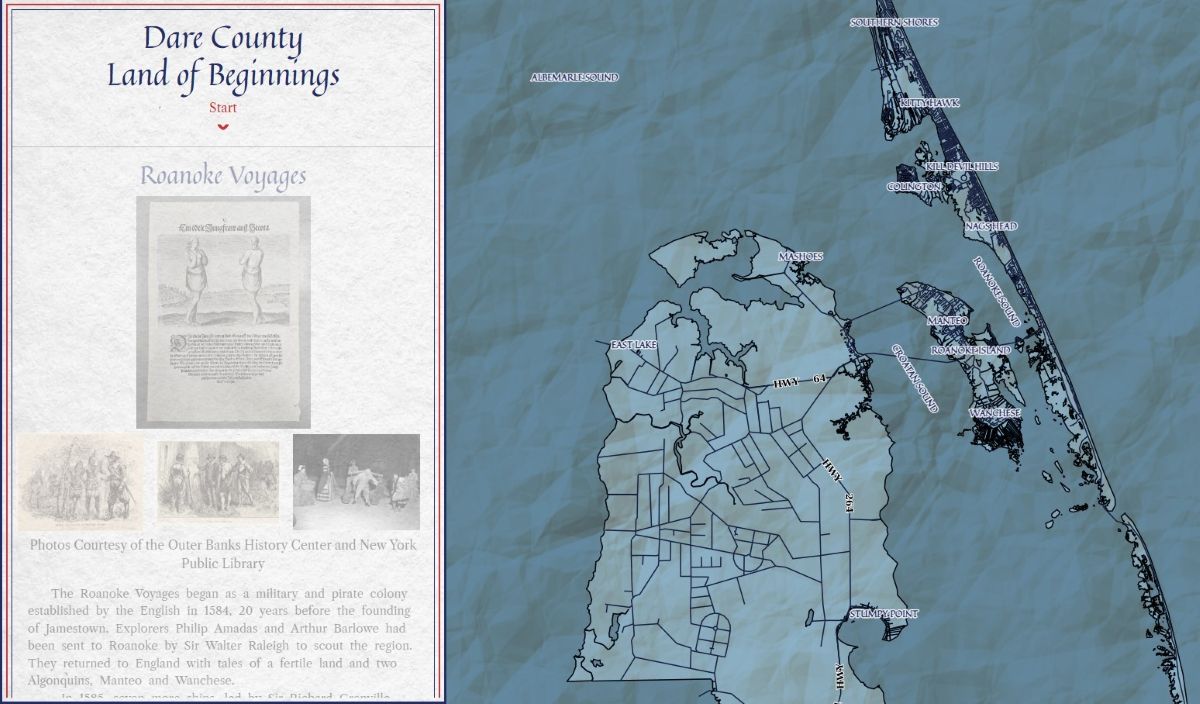

As described in “The Battle for the North Carolina Coast,” the “Land of Water” coastal system in northeastern North Carolina includes a huge “drowned-river” estuarine system that encompasses vast shorelines, marsh, swamp forest wetlands, pocosin swamps, Carolina bays and blackwater streams.

“The natural resources that constitute this “Land of Water” can play an increasingly important role in the tourist economy, a role that would revitalize the region … build on the natural and human history and the dynamic coastal resources of northeastern North Carolina within an overarching and integrated umbrella program for sustainable, water-based ecotourism,” the book said.

And indeed, much of the land in northeastern North Carolina, from ocean beaches to river shorelines, from farmlands to forests, is surrounded by a body, or several bodies, of water. The Albemarle-Pamlico estuary is the second largest in the country, behind Chesapeake.

Although still rich with wildlife and natural resources, the low-lying region, some just inches above sea level, is becoming more threatened by impacts of climate change and rising seas: increased flooding, saltwater intrusion, stormwater inundation, shoreline erosion, ocean overwash and storm surge.

“The way I think about this is, you better understand the dynamics of our planet,” Riggs said. “That doesn’t mean that you have to be a scientist. It means you have to know something about water. You have to know something about land. And that comes down to the problem of education.”

That is, people, as a society, need to understand that how and where there is growth and development cannot be unlimited or driven by profit.

Riggs says he’s had the benefit of learning over the decades from numerous other “incredible” scientists with whom he has worked together in teams, sharing spaces in classrooms and research ships. He has spent years warning about the futility of trying to control destructive natural forces, whether or not people believe they’re created by man-made causes such as burning fossil fuels. On the coast, sea walls, sandbags, and jetties ultimately make things worse by increasing erosion and will ultimately fail anyway, he has preached.

But as nightmare damages from storms, such as the recent deadly flooding in the mountains from Hurricane Helene, have increased, he said he’s noticed that people are starting to listen; they’ve realized that climate conditions are not the same as they were in the old days.

“There’s nothing wrong with the history and and yes, we can respect the history, but the history includes change,” he said. “We better understand how rivers (and oceans) work, and if we don’t understand that, there will be human disasters. The more we politically ignore the science, the bigger the human disasters.”

Next in the series: “Cape Lookout National Seashore, Paradigm for a Coastal System Ethic”: An excerpt.