It was well into what we now call hurricane season in 1879 when the Atlantic Hotel on the Beaufort waterfront began filling with hundreds of guests ahead of the North Carolina Press Association’s annual meeting taking place there in late August.

Visitors from across the state, including the then-governor and his wife, made the lengthy trek to the hotel, most arriving around Aug. 15, of that year, about the same time as rumors began to circulate that a hurricane was causing damage in the Caribbean.

Supporter Spotlight

“But nobody in Beaufort was too bothered by that. In fact, the hotel manager was told about it, and he said, ‘we haven’t had a bad storm here in over 20 years. Everyone’s going to be fine,’” Assistant State Climatologist Corey Davis explained when he began his talk on “Lessons Learned from Recent Statewide Storms” at the Down East Resilience Network’s fall gathering.

Davis is with the State Climate Office of North Carolina based at N.C. State University in Raleigh, and was one of the speakers at the get-together held Sept. 23-24 in the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island.

A project of the museum, the network meets there a few times a year to share and discuss with scientists, decision-makers and residents the latest research on the threats to Carteret County’s coastal communities such as nuisance flooding and hurricanes, and opportunities to address the aftermath.

Davis continued, fast-forward to a few days later, and warning signs began to appear that a storm was coming. “It’s the fishermen, the locals, that are the first ones to take notice.”

Then a Coast Guardsman stationed at Fort Macon on Bogue Banks began to receive telegraph transmissions from Florida and Georgia about the storm making its way up the coast.

Supporter Spotlight

The Coast Guardsman rushes to Beaufort to tell the hotel manager that a hurricane is on its way, Davis narrated, “and this hotel manager just scoffs. He said, ‘Nobody from the U.S. government is going to tell me how to run my hotel. Now you go back and do your job. Everybody here is going to be fine for the night. Well, as you can guess from the foreshadowing, they were not fine,” Davis said. “By 3 a.m. the rain had picked up. The wind was blowing even harder. The floodwaters along the ocean from the storm surge had risen to waist high by that point.”

A local then sounded the alarm to alert everyone that they needed to seek safety. The bottom floors of the hotel were already flooding, but not many people took notice.

“Now, I wish I could tell you that this story had a happy ending, but it doesn’t. This is a tragedy in our state. This is the story of the great Beaufort hurricane of 1879. It was a Category 3 storm at landfall right here in Carteret County. And in total, 46 people in North Carolina and Virginia lost their lives during the storm,” Davis said.

The hotel was rebuilt the next year on the Morehead City waterfront, only to burn to the ground in 1933.

He opened his talk with that history to give “a perspective of how these storms were perceived 100 and some years ago. Largely, that’s that hurricanes were primarily coastal events.”

Prompting him to ask what has changed when it comes to learning about hurricane behavior and forecasting, as well as why tropical storms and their hazards getting worse, and putting more folks at risk.

One change, for the good, is that forecasting has improved since the early 1970s. “What we saw back in the late ’70s, early ’80s is that the average track error at 72 hours was something like 400 nautical miles. That’s basically the distance between right here on Harkers Island and Knoxville, Tennessee,” Davis said.

Track error is the difference between where a hurricane is expected to go and the path it actually travels.

As science, modeling and forecasting have improved in the decades since, track error has decreased. “Over the last five to 10 years, that 72-hour error is under 100 nautical miles,” he said.

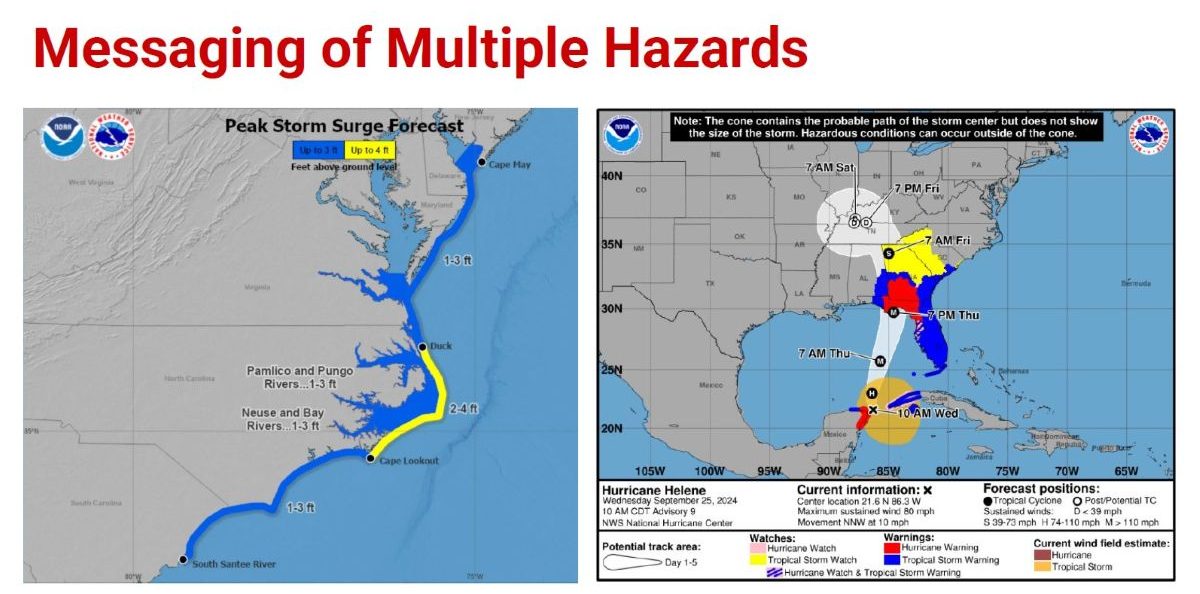

Another area of improvement, which he thinks should continue to improve, is communicating to the public the storm forecast and associated hazards.

Past messaging has focused on winds being the primary hazard, especially for coastal areas, but in recent years forecasters have emphasized rain amounts, flooding and storm surge, as well as hazards people in inland areas should expect.

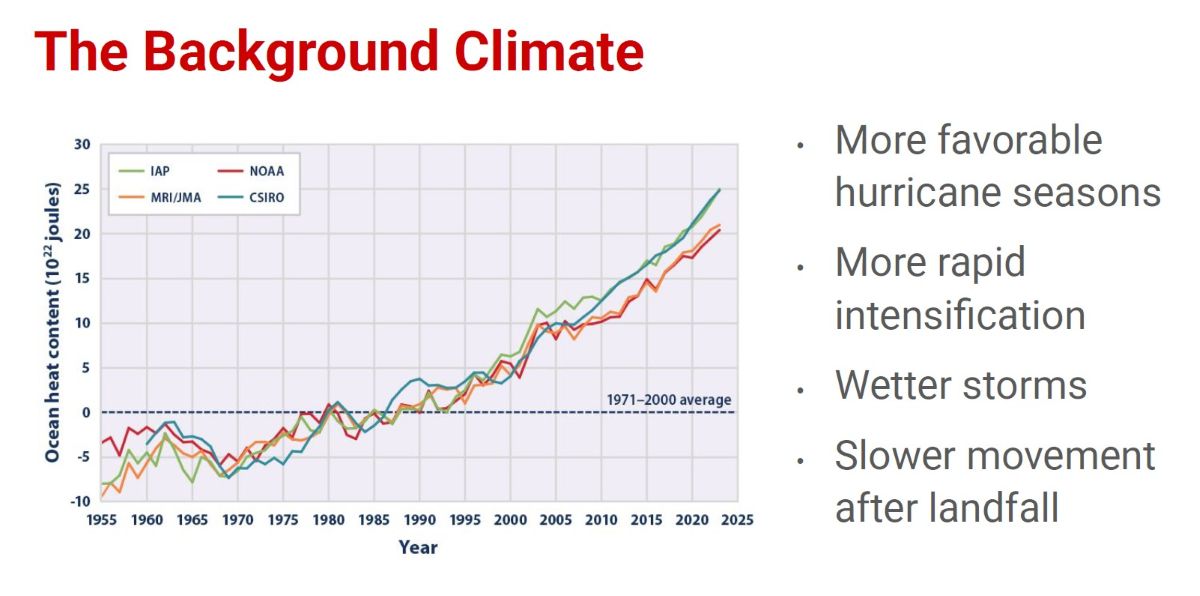

One of the changes “that we don’t have a whole lot of control over” is background climate, which includes increasing global ocean heat content, or the total amount of heat the ocean has absorbed and stored.

“We know by now that the oceans have really absorbed the brunt of the warming that’s happening, especially over the last 50 to 60 years,” he said, and there’s been a steady increase since the late 1960s or the early 1970s.

This increase has had a few different impacts on tropical storm and hurricane events.

“No. 1, when you’re seeing that much warm water present, it means more seasons will be favorable for tropical activity. Even though there can be some other environmental oceanic factors that you have to worry about, if the ocean is warm enough, you can pretty much always get storms to form,” Davis said.

Another big impact is rapid intensification, like when a storm goes from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in 18 hours, as did Hurricane Erin earlier this summer.

“Obviously, that does add to the punch that those storms bring when they get to land,” Davis said.

As for atmospheric factors, a warmer atmosphere is similar to a bigger sponge and is “able to soak up more moisture, and it tends to wring out that moisture all at once, and it is able to do that even farther inland as well. So storms are getting wetter overall,” Davis said.

Hurricane Florence in September 2018 dumped “36 inches of rain in parts of southeastern North Carolina, just unheard-of amounts.”

Researchers looking at hurricane trends have found that, especially since the early 1970s, the storms are slowing down and even stalling when reaching land, and that’s primarily for the coastal Carolinas.

“That means we see storms like Florence. They get to our coast and just slow to a crawl; they sit over us for days and drop even more rainfall than we’ve ever seen,” he said.

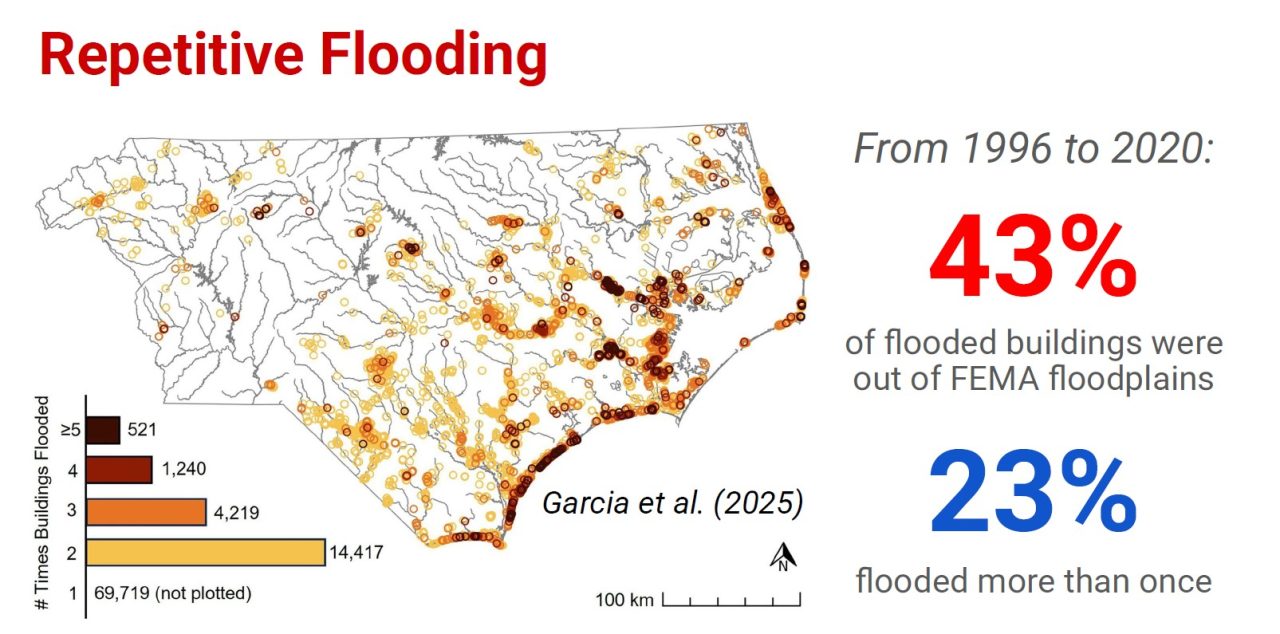

Another consequence of these changes is that more people are in harm’s way from these storms. Davis cited a study from a few years ago that found for every house in North Carolina that was removed due to floodplain buyouts, another 10 had been built in those floodplain areas.

Another study determined that from 1996 to 2020, 43% of the flooded buildings in the state were outside of the Federal Emergency Management Agency-designated floodplains, and of all the buildings that have flooded in the state during this 25-year window, 23% flooded multiple times.

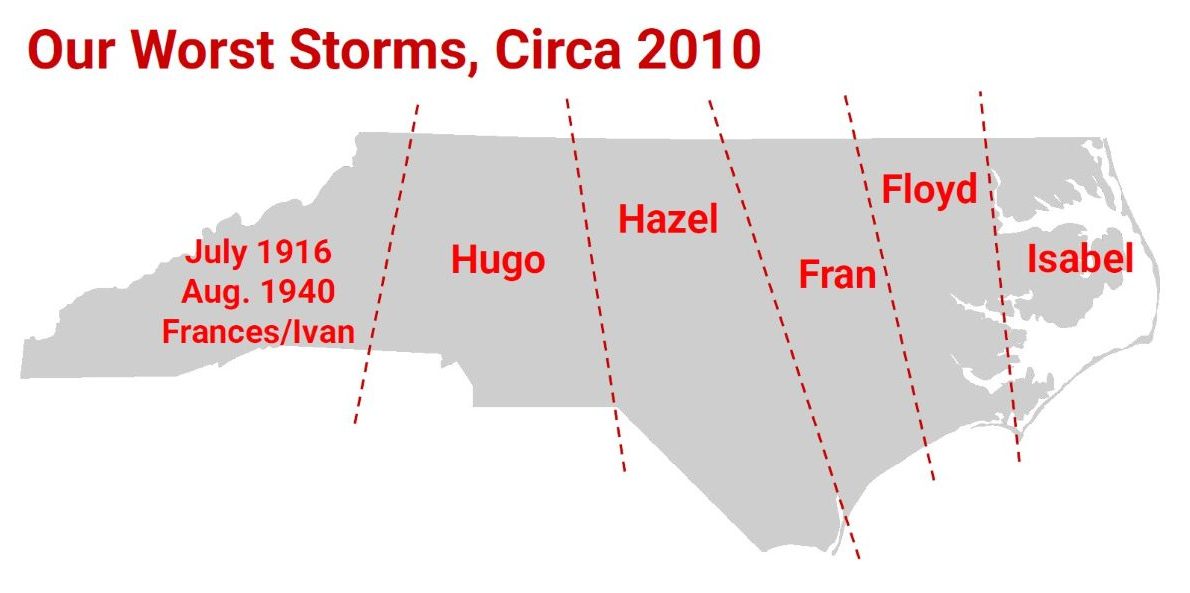

Storms look different now than they did in 2010, Davis continued, referencing a map showing the major storms most people consider the worst they experienced.

From the mountains, east, the storms were: Frances in 1916, Ivan in 1940, Hugo in 1989, Hazel in 1954, Fran in 1996, Floyd in 1999 and Isabel in 2003.

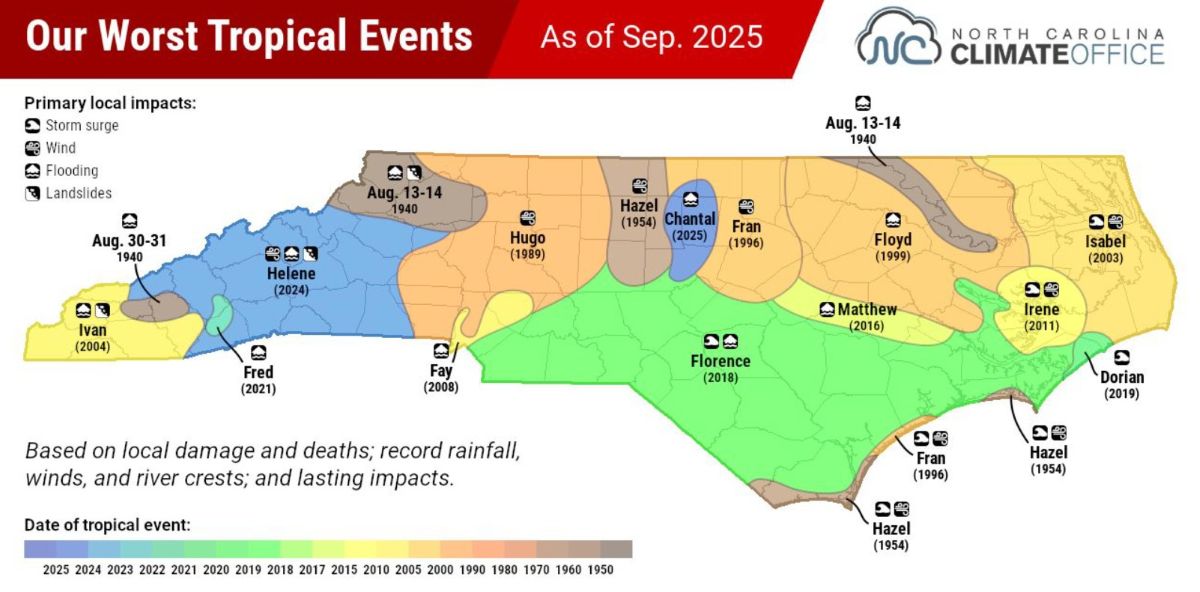

Davis then moved to a new map his office created showing the state’s worst tropical events as of September, which looks drastically different from the 2010 map.

“Carteret County is a really good example,” Davis said. “You’ve got one of those classic coastal monster storms. Hazel in 1954, a big event, storm surge in Morehead City and other parts of the coastline.”

But for the North Core Banks and Ocracoke Island, 2019’s Dorian caused soundside storm surge like those areas had never seen before. “Most of the rest of Carteret County and most of southeastern North Carolina would now show Florence as the worst.”

Fifty other counties have seen their worst storm come during the last 10 years.

Looking at the scale of some of these events, Florence can now be considered the worst storm from Cape Lookout to the suburbs of Charlotte. “That is a massive footprint that we just didn’t see historically for those sorts of storms,” Davis said.

Davis said there are things to be learned from these storms.

“The first is what I’ll call action at a distance,” which essentially means that an area can experience big impacts even if the eye of the storm remains far away.

“I know this area saw that with Erin earlier in the summer, 200 to 300 miles offshore, but you still saw the rip currents and the overwash as if it was literally right in your backyard,” Davis said.

Another takeaway, he continued, is that you can’t just look at the strength of the winds or the category to understand what a storm will do.

Tropical Storm Chantal in early July was a weak tropical depression when it moved over central North Carolina, but the 8 to 10 inches of rain over a 12-hour period was far beyond what those areas had seen before.

Davis said he’s “firmly in the camp” of if we don’t learn from history, we’re doomed to repeat it, and one of the big tragedies in eastern North Carolina was after Hurricane Floyd came through in 1999. Residents were told that it was a thousand-year event, leading people to believe a storm of that magnitude wouldn’t happen again in their lifetime, their children’s lifetime, or their children’s children’s lifetime, so they rebuilt the same as before.

“It wasn’t until we got the next storm with Matthew and the next storm with Florence, that they realized it’s probably not a great idea to have a house here, because this is not a once-in-a-lifetime event,” he said, adding that has to be emphasized to people. “If it happens once, it’ll happen again.”