Not much has changed in Sledge Forest in the more than 20 years since its distinctive features were captured on the pages of a document created to offer guidance for its future use.

That, said geologist Roger Shew, is the beauty of it.

Supporter Spotlight

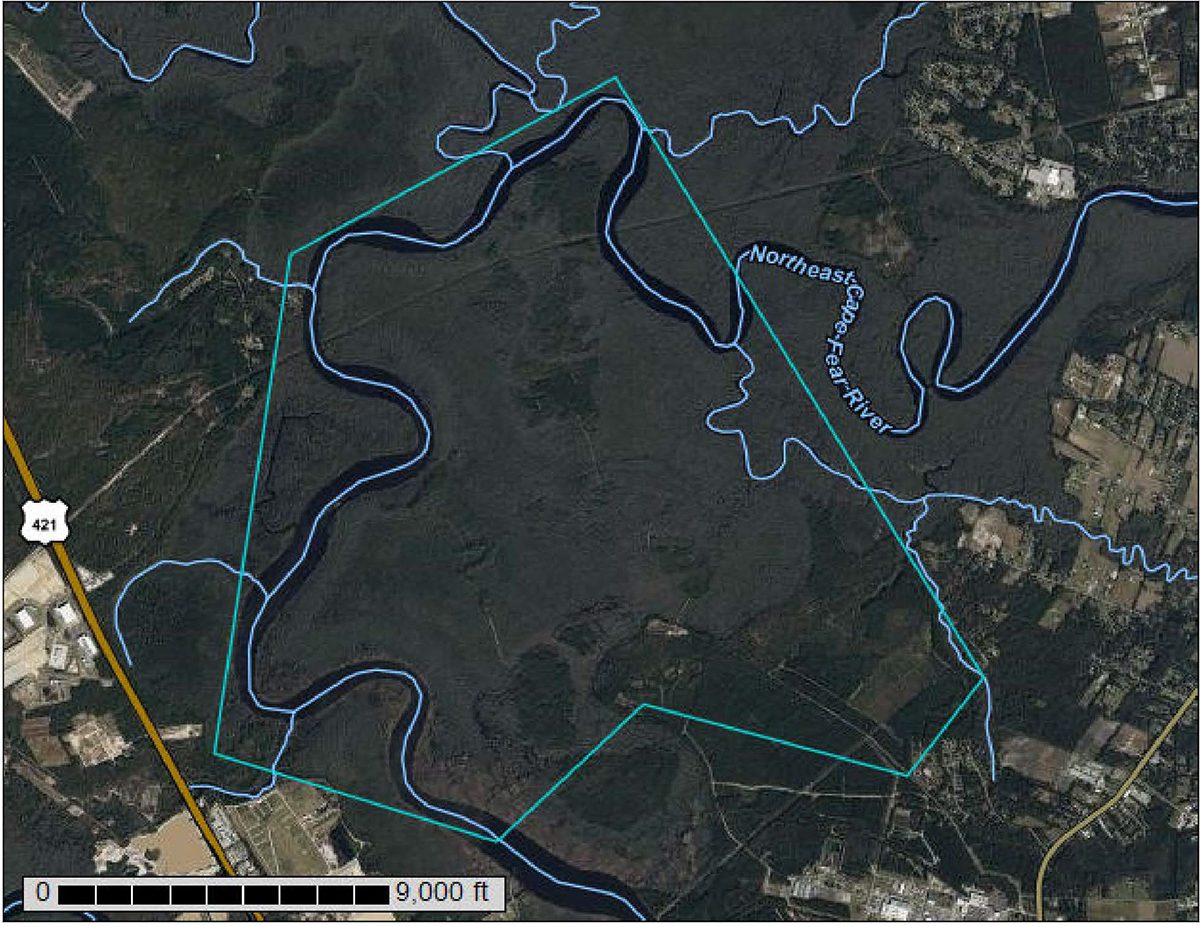

The forest that rises from the banks of the Northeast Cape Fear River and sprawls thousands of acres across northern New Hanover County is still an important part of the river floodplain, one of the largest landscape corridors in the southeastern part of the state.

Towering up from the forest bed are cypress and loblolly pine trees, some of the oldest in southeastern North Carolina, that are hundreds of years old, a “rare old-growth occurrence,” according to a biological survey published in May 2003 by the Natural Heritage Program of North Carolina, which identified the forest as a significant natural area.

The forest’s attributes have in recent weeks been thrust front and center in a rumble that tipped off when a Charlotte-based developer submitted to the county’s planning department preliminary plans to build thousands of homes on about a quarter of the more than 4,000-acre, privately owned site.

Because the land being eyed for the proposed development of more than 4,000 single-family houses, a golf course, trails and a horse farm does not have to be rezoned, the project gets pushed straight through to the county’s technical review process, effectively omitting the opportunity for public comment.

That’s simply unacceptable to Castle Hayne resident and local activist Kayne Darrell.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s a by-right property so they can go in and start clear-cutting any time they want,” Darrell told Coastal Review in a recent telephone interview. “We’re hoping they don’t yet. It’s unconscionable to me that we have no opportunity to get our questions answered or have any input on what’s happening because it’s going to impact so many of us in so many negative ways.”

Attempts to reach the developer, Copper Builders, LLC, were unsuccessful. An engineer listed on the development plan application did not return a call for comment.

The homes of Hilton Bluffs, the name of the proposed development, would be built on about 1,000 acres of uplands that adjoin about 3,000 acres of protected wetlands, those that have a continuous surface connection to the U.S. Supreme Court-defined “waters of the United States” – in this case, Prince George Creek, which connects to the Northeast Cape Fear River.

Sledge Forest is one of the largest tracts along a more than 35-mile stretch of the floodplain corridor running from Holly Shelter Creek, at the north, south to Smith Creek.

Shew, senior lecturer in the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Ocean Sciences and Environmental Sciences department and a conservationist, said in an email response to Coastal Review that the forest is dominated by hydric soils that are “periodically inundated during high-tide flooding events and storm events.”

Such floods are forecast to only increase with sea level rise, the latest projections of which are a minimum of one foot by 2050.

“High-tide flooding is common along the river and has the potential to inundate much of the site,” Shew said. “And, in the future … most of the area will be inundated fully or partially with river waters. Putting golf courses, horse barns and cabins or single-family homes in this area are ill-advised.”

The roads that will connect those neighborhood amenities will have to be built over wetlands, which will, in turn, block water movement, Shew said.

“And of course, whatever (fertilizer, herbicides, etc.) is put on these areas will runoff into the surrounding wetlands and river,” he wrote.

“The best and most logical use of this land is for it to be left as a natural area that supports wildlife, rich plant communities, corridor connectivity, reduces floodwaters, and maintains all of the ecosystem services of these wetland communities for the benefit of our community in a way too fast-growing area in northern (New Hanover County),” he said. “We need to have a comprehensive plan that maintains large natural areas and this and parts of Island Creek are sights that would be best and be opportune investments for the county for its future.”

Most of the old-growth trees are largely within the project building footprint, Darrell said. A 2003 natural area inventory dated cypress to be more than 350 years old and estimated to be as much as 500 years old, and dated loblollies to be more than 300 years old.

Area residents are also concerned about what is projected to be a significant increase in traffic on rural roads in the area – more than 30,000 additional vehicles per day.

Inactive hazardous site abuts tract

Opponents of the proposed development say they’re also troubled by the fact that the development is being proposed on land that is adjacent to a state-designated inactive hazardous site.

According to information provided by the North Carolina Division of Waste Management, contamination at the site off Castle Hayne Road resulted from drums of calcium fluoride and lubricants being stored in unlined trenches during the 1960s and 1970s.

That contamination spreads across two parcels, one of which is owned by General Electric.

Contamination in groundwater in the northwest corner of GE’s roughly 100-acre tract includes uranium, vinyl chloride and fluoride.

Those contaminants spill over onto a neighboring 1,500-plus-acre parcel owned by Nuclear Fuel Holding Co. Inc., a GE affiliate, according to Securities and Exchange Commission documents.

There are also contaminants in groundwater around the main plant on GE’s property. Those contaminants include tetrachlorethylene (PCE), trichloroethylene (TCE), cis- 1,2-dichloroethene, 1,1-dichloroethane, vinyl chloride, benzene, and naphthalene contaminate, according to the state.

Contamination at the main plant area is contained on-site, but is also close to the northern central property line, said Katherine Lucas, public information officer for the Division of Waste Management, in an email responding to Coastal Review’s questions.

“A portion of the (northwest) Area Contamination has migrated to the adjacent property in the deep groundwater aquifer,” she said in the email.

The site was added to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch inventory in 1988.

The department’s Division of Water Resources conducted regulatory oversight of all remedial activities at the site until 2008, when site management was transferred to the branch as part of a reorganization between the waste management and water resources divisions.

The site was added to the branch’s Site Priority list in 2008.

“The area of the contamination has not been calculated,” Lucas said. “Ground water contamination is being remediated with a series of hydraulic control wells and pump and treatment of contaminated groundwater.”

More than 3,500 people have signed an online petition to save Sledge Forest.

Darrell, who helped organize Save Sledge Forest, said the ultimate goal is to get the land in conservation.

“That’s where it belongs,” she said. “We’re not giving up. It’s too special a place.”