DUCK — For a few days this summer, three split-hull barges chugged south from Norfolk, Virginia, to deposit 6,500 cubic yards of olivine sand mined in Norway at a nearshore area of this small oceanfront town on the northern Outer Banks.

But with completion of the barge’s work in July, there’s no visible evidence that the trademarked Coastal Carbon Capture pilot research project is underway. The Vesta company project is to test whether olivine sand could permanently remove tons of carbon from the atmosphere and the ocean.

Supporter Spotlight

“So, I think ultimately, at the end of the day, it was a successful deployment in the sense that we’re set up for monitoring this project and getting the scientific results out of it,” Zach Cockrum, vice president of policy and partnerships with Vesta, told Coastal Review this week.

As the company’s website tells it, it’s taken decades of collaborative research to get to the point where data can be collected to support Vesta’s belief that plentiful and natural olivine could, if not outright save the planet, at least mitigate the problem.

“We could reverse climate change,” the company says on its website.

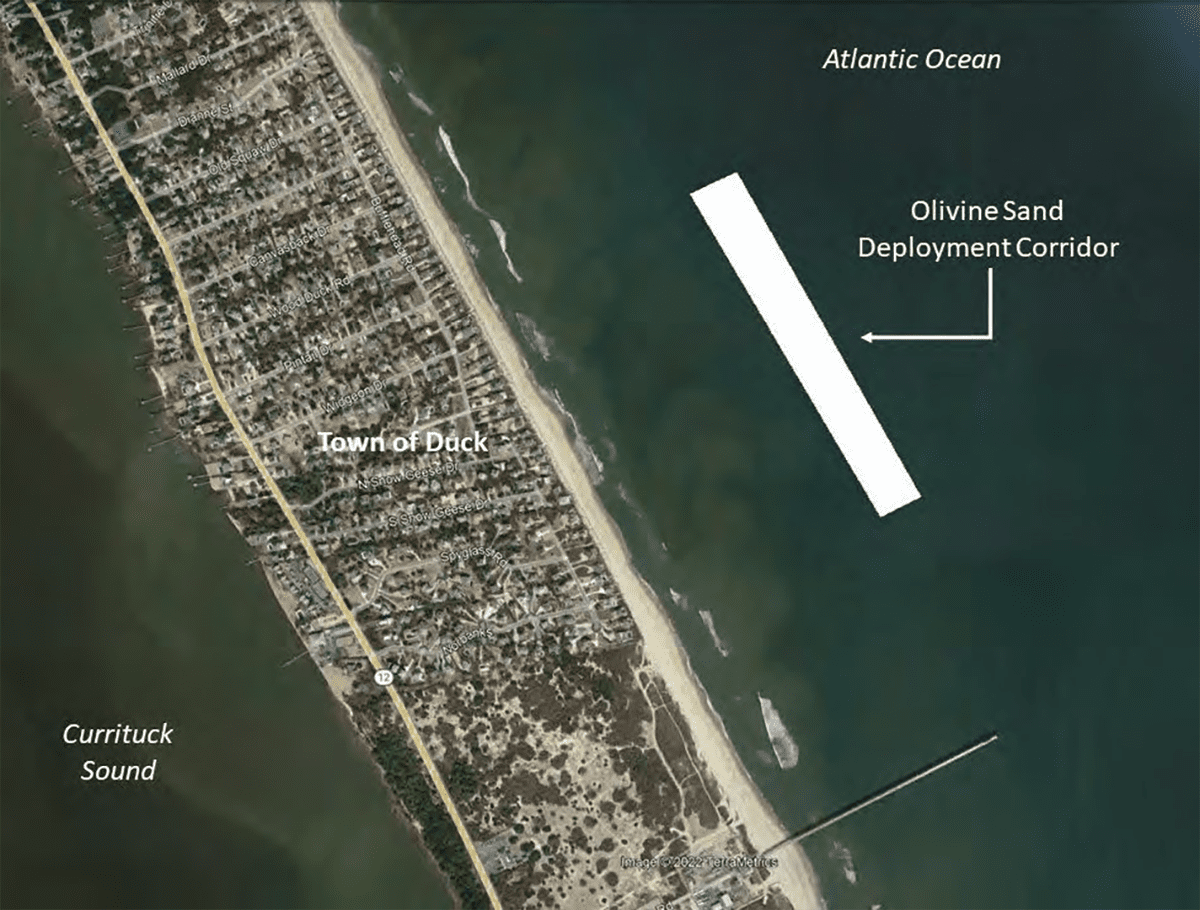

Vesta, which is permitted under the federal Clean Water Act and the state Coastal Area Management Act, has contracted with Hourglass Climate, a U.S-based nonprofit research organization, to monitor the site for two to three years. The site is a 300-foot-by-2,200-foot corridor situated 1,500 feet offshore of Duck’s beach in 25 feet of water.

Olivine, which has a light green tint, is a common magnesium silicate mineral similar to the quartz in Outer Banks sand. When it dissolves in seawater, it has the unique ability to remove carbon from the atmosphere and reduce acidity in the ocean.

Supporter Spotlight

Although olivine is not uncommon — there’s plenty in western North Carolina, for instance — Vesta’s coastal research is novel, including its two earlier projects testing olivine as part of shoreline replenishment and in a small area of marsh.

“But these pilot projects, using olivine in these coastal settings like this, is something that Vesta alone is doing, as far as we know, in the world,” Cockrum said.

According to company estimates, the Coastal Carbon Capture pilot project could remove at least 5,000 tons of carbon dioxide from the ocean and atmosphere.

Eventually, the goal is that olivine, milled down to compatible grain size, could be integrated into beach nourishment projects, making the projects more affordable while helping to reduce carbon pollution. The olivine does lose its carbon removal ability over time, but further research is needed to determine how often it may need to be replenished.

As an alkaline material, olivine reacts with the carbonic acid, which contains carbon dioxide, as it weathers in the seawater. In the process, the acid is converted to bicarbonate, which provides long-term carbon storage.

Hourglass has a service agreement with the nearby Army Corps of Engineers Research and Development Center Field Research Facility, known locally as the Duck Pier, to use their equipment, vessels and amphibious vehicles at the site, Cockrum said.

“And then the researchers at the Army Corps are also looking at the sediment transport, how the olivine is moving in that ecosystem,” he added. “And that’s something that they’re interested in, outside of the carbon removal aspect of it, because olivine is a traceable mineral, so it’s helping them understand the dynamics of that coastal system.”

Hourglass is using “benthic flux chambers” that are placed on top of the sand for about a week to take consistent measurements of water over the sediment, Cockrum explained. There will also be sampling to look at benthic organisms in and around the olivine, as well as the surrounding ecosystem, and the carbon removal will be measured.

Since olivine is a natural mineral found on numerous locations, the issue is not its inherent safety; it’s what its impact would be to an ecosystem, as well as its carbon-removal ability, where it is not naturally occurring — hence, the testing at Duck. But not all olivine deposits react the same.

For instance, Papakolea Beach in Hawaii is notably green from its high olivine content. But it’s a different scenario, scientifically.

“I think the data on the naturally occurring beaches is complicated because of differences in grain size,” Cockrum said. “Like this gets way into the weeds of finer grain olivine dissolves more quickly, and therefore releases or captures carbon more efficiently. So, there are differences between the sort of existing beaches that are out there and what we’re hoping to do in these different settings. This is another thing that we’re looking at paying close attention to when I talk about how efficient is carbon removal.”

Part of the funding for research has been provided from the Coastal Carbon Capture Development Fund, a 501(c)(3) public charity. The project monitoring is also being supported by University of North Carolina Greensboro, UNC Wilmington, and the Coastal Studies Institute at East Carolina University Outer Banks Campus.

Vesta is promising to share monitoring results publicly, including with regulatory agencies, and will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Vesta’s monitoring partners are already starting to get some data back, Cockrum said.

“We’re in the process of basically analyzing that data and figuring out the best way to share it,” he said.

One of the most important goals of the pilot project is for data to establish how much carbon is being removed, and how quickly. And if it’s as the researchers are hoping to see, olivine could be elevated from its modest mineral status to a savior of the planet. Or at least a natural helper.

“So, we go from here to really honing in on what is the coastal protection benefit,” he said. “Just in general, the coastal protection industry, whether it’s the Corps or any number of communities, they’re all looking for different sediment sources. And so, our hope is that we can be an affordable source of sand for any number of coastal protection projects.”