Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

At first light we gathered at the Friendship Holiness Church, down on the edge of the great swamp country that makes up the headwaters of the Lockwoods Folly River.

Supporter Spotlight

The church is in the heart of a community called Piney Grove, which is in Brunswick County, North Carolina, between the little town of Bolivia and the Green Swamp.

This was just a few days ago, on the Monday morning of the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. The day broke chilly, but the only clouds that I could see in the sky were far to the east, over the Atlantic, and they were a breathtaking shade of red.

I remembered the words in Homer’s “The Odyssey”: “Child of morning, rosy-fingered Dawn.”

I always love going to Piney Grove. My friend Marion Evans is the keeper of the community’s stories and she’s a fantastic local historian, as well as just a really special person.

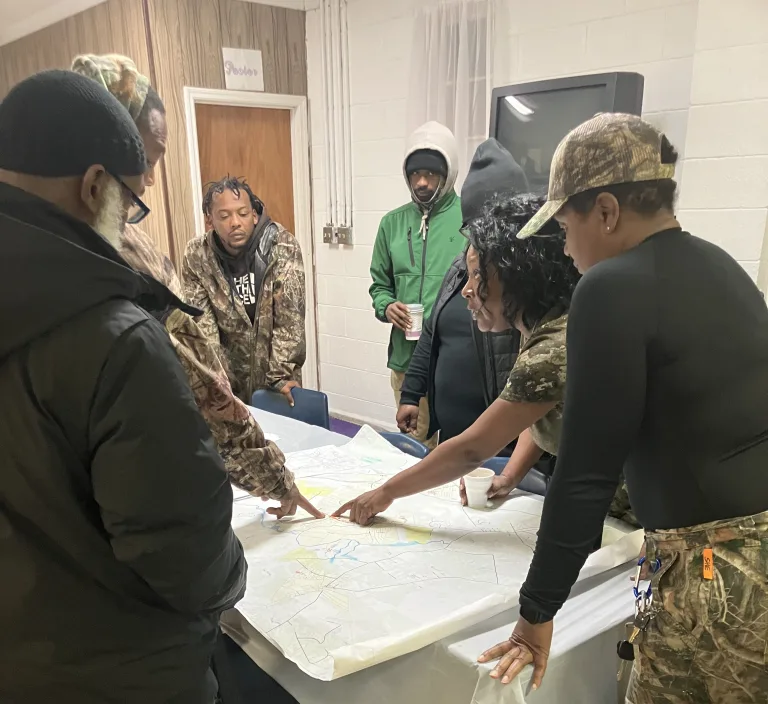

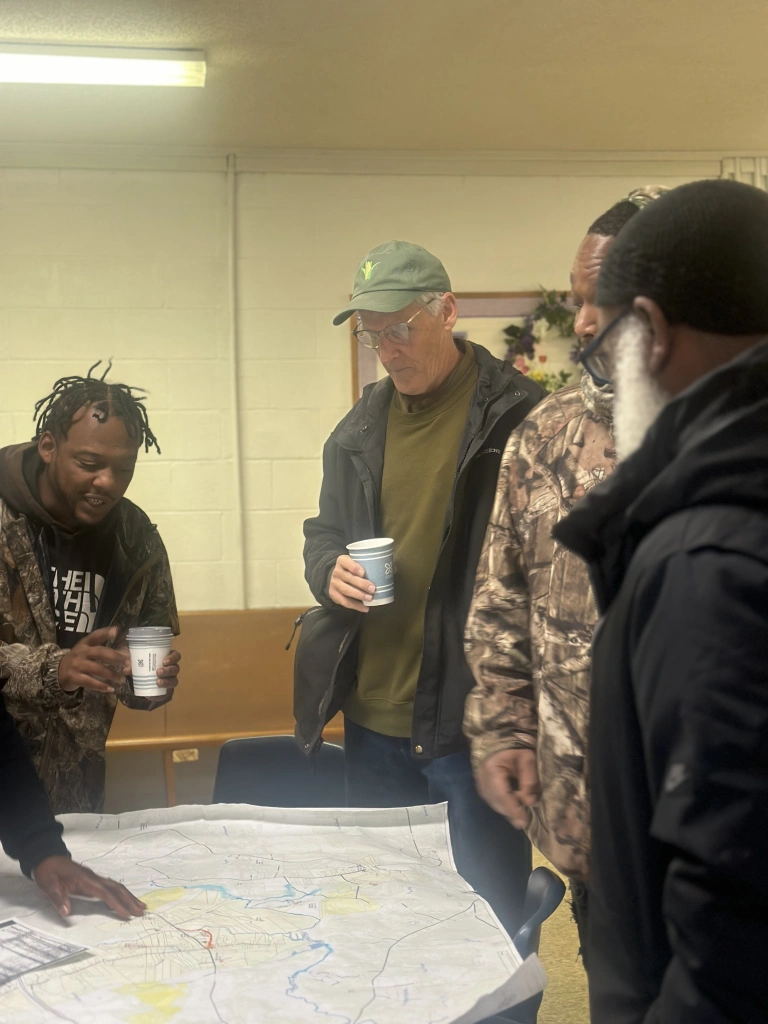

Marion had invited me to spend the day with 25 or 30 of her family members as they went in search of the community’s history in the local woods and swamps.

Supporter Spotlight

Their ancestor, Caesar Evans, had escaped from slavery during the Civil War and fought for his freedom in the Union army. After the war, he and his family had worked and saved until they could buy 228 acres there in that central part of Brunswick County.

I highly recommend a visit to the Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington to see Marion’s wonderful short film about the life of Caesar Evans and the birth of Piney Grove. It’s running continuously as part of the museum’s Monument exhibit thru March 31.

You can also learn more about Marion Evans’ remarkable work on Piney Grove’s history in my story “A Day in Piney Grove: A Journey into Brunswick County’s Past.”

That land became the community of Piney Grove, and with the exception of me, everybody there that morning was one of Caesar Evans’ descendants and a son or daughter of Piney Grove.

I just felt lucky to be there. It’s a wonderful family, and I was excited to spend a day with them.

We had a number of goals for the day. First, we were hoping to find the site of an old tar kiln that was run by the Evans family at least in the early 20th century and probably quite a bit earlier.

Marion’s sister Melissa had found the site of the tar kiln marked on a 1913 survey chart of the family’s land. She had brought the survey chart to the church with her.

The family was also hoping to find several other sites that their elders had told them about when they were young.

Those sites included the community’s old cart road, two or three burial grounds, a haunted spot or two (so the old people said), a shingle mill’s tram road, and a low-lying place deep in the woods that the community’s elders had simply called “The Hole.”

According to Marion’s grandmother, The Hole was a place of refuge down in the swamps. Before we left the church, Marion explained that it was “the place where they used to hide.”

Everybody except for me seemed to understand exactly what that meant without any explanation, but I had to ask.

Vinnie Joyner, one of Marion’s cousins, explained The Hole to me: In the old days, he said, they took shelter there when the nightriders came.

He explained that their ancestors always had a plan for evacuating the community’s children quickly to The Hole and for defending themselves once they were there.

Some of the ladies made a wonderful breakfast for us in the church’s annex, then we headed out into the woods. Nearly everybody was on foot, though two of the guys did ride their ATVs until the woods got too thick for them.

We had the survey chart to help guide us, but we relied more on the young people.

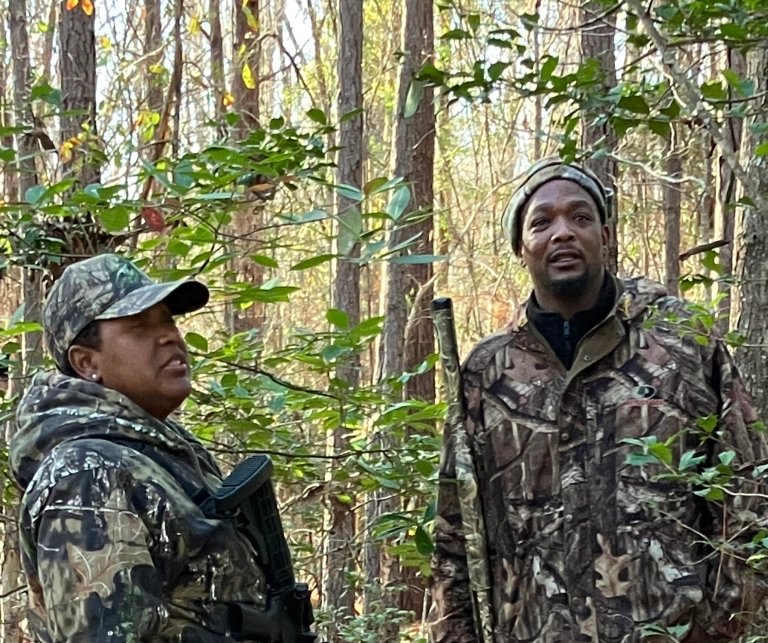

Most of the young guys and at least one of the young women were hunters and knew those woods inside out. A few of them had brought their shotguns, or more, and seemed ready for anything.

The whole day was just a delight. We found everything we were looking for, except for the tram road, and a few other things, too. And now and then, we’d all pause and Marion or one of her relatives would tell a story, often a tale that they remembered hearing when they were children.

As we wandered deeper into the forest, the sun rose above the trees. The day warmed up. The woods and swamps came out of the shadows and we could take in the beauty of the land in all its glory.

Spirits were high, too. Even when the undergrowth was so thick that we could only see a few feet in front of us, the forest was filled with laughter and the sounds of storytelling.

I am writing this at a hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, where I am waiting for a friend to finish up a round of treatment.

And as I think back on my day in Piney Grove, I guess I remember two things most of all.

Both will make me sound like an old fogey, but well, we are who we are.

First of all, I remember the kindness and almost old-fashioned solicitousness of Piney Grove’s young people.

Again and again, they helped me and the other older people across creeks and ditches and opened our way through overgrown paths by pushing brambles aside or holding back branches.

Personally, I don’t think that I always needed so much help, but the young guys did it with so much generosity of spirit that it did just kind of warm my heart.

And I remember one of the young men, a gentle soul named Javelin Bell, who saw at one point that I was feeling a little unsettled as we crossed along the edges of a big swamp.

He just came over and whispered real soft like, “You don’t have to worry about nothing. You’re with family.” And after he said that, I didn’t worry anymore.

As much as that meant to me, something else meant even more.

I have to confess that, in my line of work, I have grown accustomed to it being older people who care most about the stories from our past.

In many settings where I go to talk about history, the room is full of people who are at least as old as I am. I don’t mind that — I’m interested in sharing the little I know with people of any age. But I do notice how rarely young people are in the room.

But the young people of Piney Grove were different. When Marion paused to tell a story, they crowded near to hear her.

And when some of the young people asked me about Abraham Galloway, they crowded around me.

Abraham Galloway, the subject of my book “The Fire of Freedom,” had family roots in that part of Brunswick County; his mother came from the area around Piney Grove.

Their enthusiasm, and the joy they took in the day, seemed boundless.

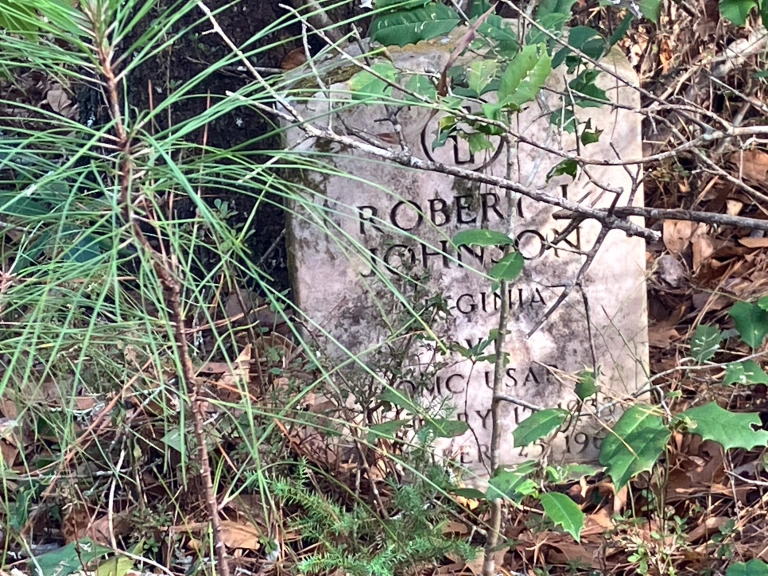

When we found an old graveyard, the young people didn’t stop until they removed the leaves and the dirt around every last headstone so we could all read the inscriptions.

And whether we were exploring one of the burial grounds or standing by the old refuge that they called The Hole, those young people showed a kind of respect and reverence for the sacredness of those places and for the importance of the stories that made me instantly and forever lose my heart to them.