Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who shares on his website essays and lectures about the state’s coast. He brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives where he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

Supporter Spotlight

I have recently been absorbed by a photograph album that the staff at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Office of History discovered in their historical collections a few years ago.

The name of the photographer who took the photographs in the album is unknown, but they are a treasure.

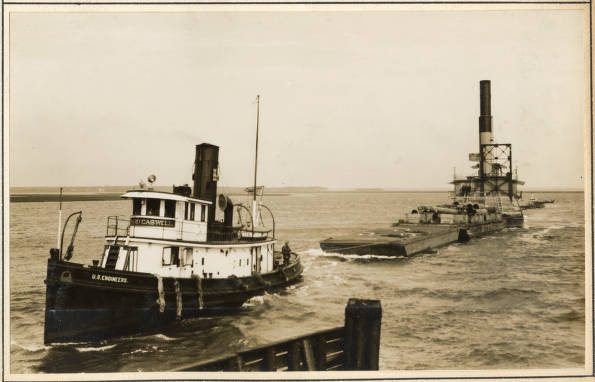

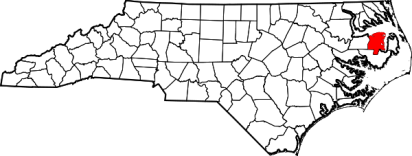

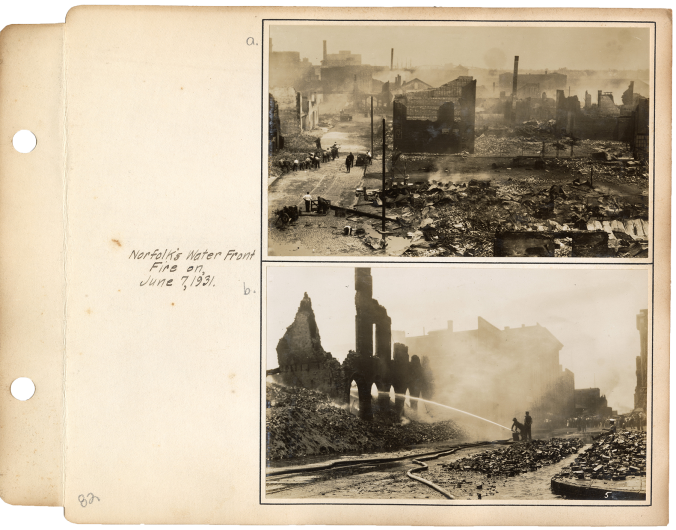

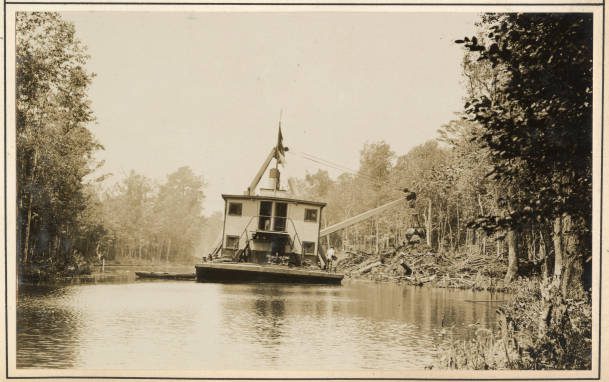

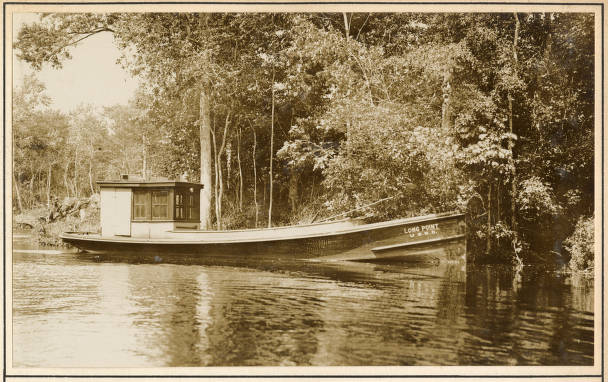

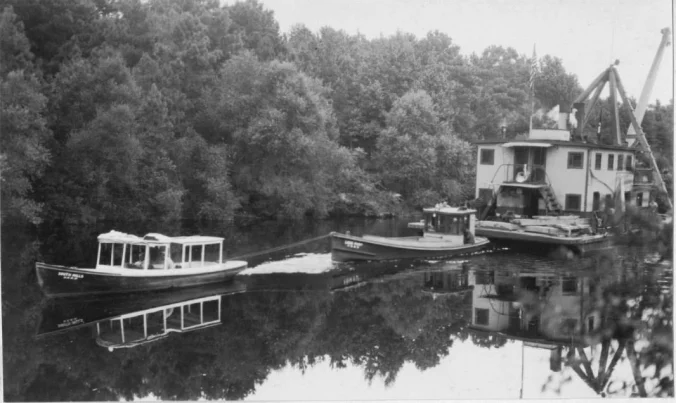

Dating from 1930 to 1932, the album’s photographs make up a rare, up-close portrait of Army Corps of Engineers’ dredging crews and dredge boats engaged in maintaining and improving navigation on the hundreds of miles of coastal waterways between Norfolk, Virginia, and Beaufort.

That 200-mile stretch of coastline composed the Army Corps’ “Norfolk District,” headquartered in Norfolk.

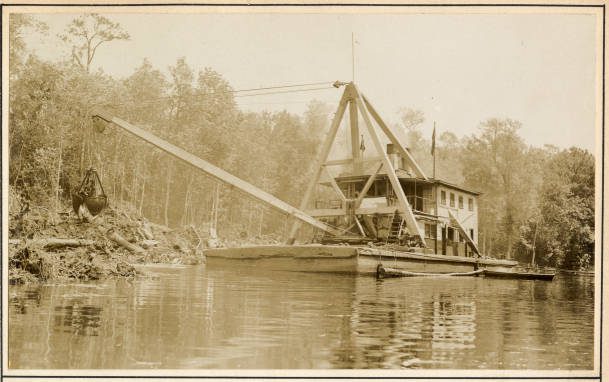

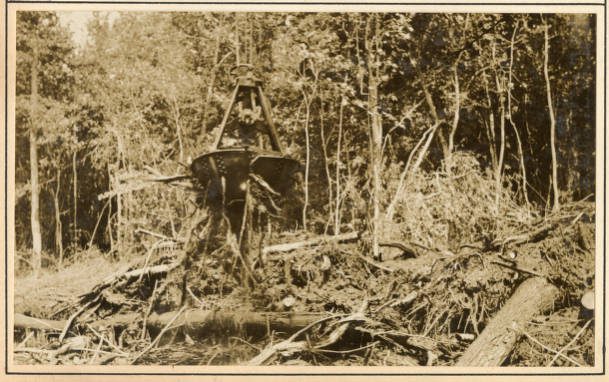

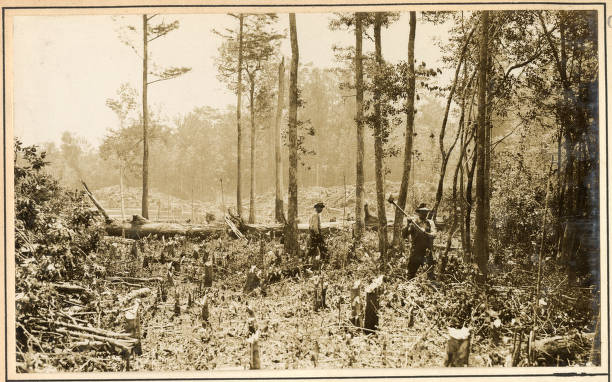

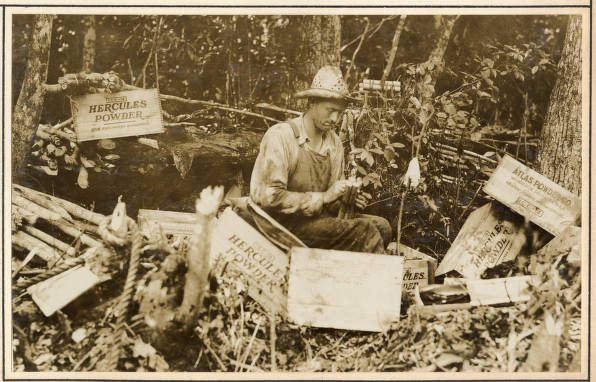

The whole album is fascinating. However, my favorite scenes are probably a series of photographs from the Scuppernong River in the spring of 1931. They chronicle the crew of one of the Army Corps’ derrick barges clearing snags, dynamiting obstructions, and straightening the banks along the narrow, upper reaches of the river.

Supporter Spotlight

Dredging on a small, remote, out-of-the-way blackwater river such as the Scuppernong was a bread and butter job for Army Corps in those early years of the Great Depression. However, I can’t remember ever seeing that kind of work captured so fully in photographs.

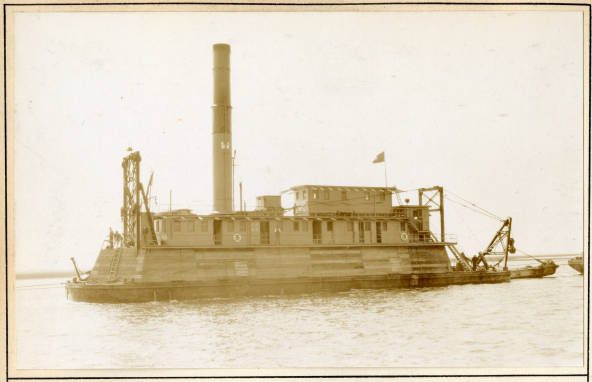

Overall, the photographs are quite varied. The album even includes, for instance, a half-dozen photographs of Army Corps’ big pipeline dredge Currituck barreling through Beaufort Inlet on its way to build a new section of the Intracoastal Waterway.

In my experience, those of us who study maritime history rarely give much attention to dredging crews and their watercraft.

Working on a dredge boat was hard, dirty work. A bit like being a sailor, a bit like being a miner, a bit like being a heavy equipment operator, and a bit like being a pipe fitter and a mechanic, too.

The crews often lived on their boats for months at a time. They were not getting rich, and they moved from work site to work site, getting home, if they had a home, when they could.

Throughout the 20th century, many dredging crews all over the East Coast came from villages on the North Carolina coast.

They came from some coastal communities more than others. At Ocracoke Island, on the Outer Banks, for instance, or in Otway, in the Down East part of Carteret County, you would have been hard pressed to find a single family that did not have a father or a son who had not worked on a dredge boat at one time or another.

The Army Corps’ Norfolk District Photo Album, 1931-32 includes 99 photographs in all. You can now find them all online at Army Corps’ Digital Library.

I have picked out a selection of the photographs to highlight here. You will find them below, along with my annotations about the places, people, and activities depicted in them.

I have also included an especially striking photograph taken on the deck of the dredge Currituck that I found at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

It is an up-close view of the Currituck’s cutterhead, the mammoth dredging tool that her crew used to dig much of the Intracoastal Waterway along the North Carolina coast.

The Mariners Museum, by the way, has copies of the Army Crops photographs in its library. You can access them online.

I don’t think this is the time to discuss the overall historical impact of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on the North Carolina coast, either for the good or the bad.

However, I think that I should note that few entities of any kind have shaped either the geography or economy of the North Carolina coast more over the last 150 years.

Resting in the hands of the Army Corps’ dredging crews and those of its private contractors has been the very shape of our coastline and the character of much of maritime life and work.

That has included the depths and commercial viability of our harbors; the fate of our seaports; how far our rivers can be navigated; which inlets are navigable and which are not; where ferries can run, and where they cannot; where boats can find refuge; how vulnerable, or not, coastal towns are to hurricanes; and where, if at all, our commercial fishing fleets can get to sea, among much else.

In those same hands, again for better and for worse, has been the fates of whole coastal ecosystems.

Yet in all my years of studying the history of the North Carolina coast, I have never seen a book, a museum exhibit, or a historical marker about that part of our maritime heritage.

Many a time I have looked out onto a harbor or an inlet and watched a dredging crew at work and wondered what their lives were like, and how they do what they do, and what it is like to endeavor to shape and bend the sea and shore against nature’s will.

Of course, the photographs in the Army Corps’ Norfolk District Photo Album, 1931-32 are far from the full story.

They only show us a brief moment in history, and just a few waterways. But to me they are still invaluable. At the very least, they give us a glimpse of this usually unseen part of our maritime history and leave us with a yearning to know more.

* * *

The following is a selection of the album’s photographs and a little background on what is happening.

-1-

-2-

-3-

-4-

-5-

-6-

-7-

-8-

-9-

-10-

-11-

-12-

-13-

-14-

-15-

-16-

-17-