Second in a series.

Aerial photographs that capture ghost forests, pilings jutting up from the water in Hatteras Inlet, the narrow two-lane N.C. Highway 12 at North River Bridge, and oceanfront homes with waves lapping at the front steps were hanging in the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island in late June 2018 as part of a multimedia exhibit showing climate-related change.

Supporter Spotlight

“Rising: Perspectives of Change along the North Carolina Coast,” featuring 15 photographs accompanied by firsthand accounts, was on display when Hurricane Florence lingered over eastern North Carolina just a few months later in mid-September, amplifying and exacerbating the changes focused on in the exhibit.

In the very room where the exhibit survived the storm, its co-creator Ryan Stancil and a gathering of Down East residents, community leaders and academics in September revisited that scene from five years ago when the storm hit and then, its aftermath. Stancil and Dr. Barbara Garrity Blake had collected the oral histories to accompany Baxter Miller’s photography for the exhibit funded by North Carolina Sea Grant.

“Five years ago, this world changed swiftly,” Stancil said Sept. 13 to those participating in the two-day community conversation, coordinated by the Down East Resilience Network.

The network is made up of researchers, agencies, educators, students, advocates and others invested in adaptation and resilience was formed three years ago to raise awareness of the environmental changes taking place in the region.

“Florence sank her teeth into Down East – gnashing at the banks, shoving water up through the marsh and into the 13 unincorporated villages,” Stancil continued. “She dumped nearly 30 inches of rain and left in her wake damage and flooding like we’ve never seen. Homes destroyed, business at a standstill and livelihoods in jeopardy.”

Supporter Spotlight

People Down East were battered and bruised, “But, if you know anything about Down East, you know the people are strong, self-reliant and resilient,” and in the days, weeks and years that followed, they held close to each other, neighbor helping neighbor.

“So much has changed since Florence came ashore,” Stancil said. “10 years ago, we were asking what was happening around us. Five years ago, we were asking what we could do to fix it. Today, we are asking, ‘How can we buy more time?’”

Stancil said that the museum’s executive director, Karen Willis Amspacher, has said that “Rising” had inspired the community conversation.

“Sure, ‘Rising’ might play a small part in why we’re here today, the truth is, today’s conversation was inevitable,” he continued.

“There is a different sort of storm brewing – one of eroding shorelines, migrating fish, intruding saltwater, and inundated roadways. And Down East is smack-dab in the middle of that storm’s path,” Stancil said. “The people who live here aren’t the only ones who know it.”

In the last five years, Down East has attracted the attention of most of the state’s academic institutions and state agencies, and there’s at least a dozen research projects taking place in the communities.

“I’m grateful to see the interest and engagement of so many researchers as we all work to open doors of communication. We must work together to better understand the science and its intersection with place and people and policy. I believe the work we are doing here today can be a foundation for resilience building, in unincorporated communities across North Carolina and beyond,” he said.

What is changing?

The fishing industry is having to navigate changes in water quality, development and once-reliable species migrating.

Hardy Plyler with Ocracoke Seafood Co. said he had been told several times long ago by an Ocracoke fisherman that fish populations are controlled by natural cycles and are influenced by climatic events — hurricanes, freezes, salinity changes, droughts — many things that are in the natural world that affect these fish over and above regulations by the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries.

Fish also are influenced by environmental factors like pollution, agricultural runoff, municipal wastewater, and industrial pollution. When you have a big rainstorm in coastal North Carolina, pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers wash off the farmland into sounds and rivers, he added.

Adam Tyler, owner of Harkers Island’s Core Sound Oyster Co., said one of the biggest challenges on the coast he’s seeing is development and hardened shorelines. He said that living shorelines, rather than seawalls or bulkheads, are an effective way to protect the coast and promote resilience.

Tyler said there’s a marshy property a half-mile from the water under development in Carteret County that he knows won’t perk, and is being backfilled. Tyler said he didn’t know how that could be allowed.

“And then I asked one of the guys who built the home down here, and he told me, he said, ‘son,’ he said, ‘When you know the right developer and you got enough money, anything can be done.’ That conversation was about six weeks ago,” Tyler said in mid-September.

Adding that the commercial fishing industry “always get blamed for everything,” Tyler said it’s not responsible for all the coastal environmental damage.

“It’s not all us. I’m not saying that we don’t bear some burden there, but it’s not all of us. It’s the people coming in here backfilling these marshes and destroying the ecosystem. I see that all the time.”

Tyler said his frustration with regulatory agencies encouraged him to transition to oyster farming to keep himself on the water and instill in his son the proud Down East heritage.

Raleigh’s Locals Seafood Market owner and co-founder Ryan Speckman said he’s seen the shrimp fishery change since 2010, and the company has been having a hard time getting the popular bottom fish — snapper, grouper, sea bass, triggerfish — that used to be reliable almost year-round.

Speckman said that, traditionally, they’d get their bottom fish from the southeastern part of the state, the coast from Carteret County south, but he’s seen more triggerfish in waters north of Hatteras than in the southeast during the last two years.

Because the Raleigh-based company sells fresh, local seafood bought almost daily from fishermen along the coast, Speckman said he hears feedback daily, including that some species once abundant on the North Carolina coast have moved north.

‘We don’t have to wait for these changes’

Ghost forests are another visible environmental change Down East, and in much of coastal North Carolina.

Duke University professor and ecosystem biologist Emily Bernhardt explained that these dead and dying trees are “an iconic symbol of rapid change” on the coastal plain.

“There’s always hurricanes blowing salt onto the landscape, and there’s trees dying. But in the past, those trees would come back,” Bernhardt said. “What we’re seeing now is that we’re having a lot of ghost forests forming, and the trees are often not growing back.”

When a coastal forested wetland is lost, and can’t grow back because the soil is too salty or too wet for trees to grow, it is a fundamental change to the ecosystem.

“The big question I’m interested in is, what is going to happen to the ecosystems and communities of the eastern coastal plain over the next century? What makes these systems and people and communities vulnerable? What is the impact that we’re already seeing? And that we can expect? And then the big question, which is not a scientific question, it’s a human question, is, what is going to happen next?” Bernhardt continued.

The conversation about rapid environmental change taking place in this country implies it’s going to happen in the future, Bernhardt said, but there are areas already subject to widespread tidal flooding, called recurrent or nuisance flooding. “We don’t have to wait for these changes.”

During hurricanes and tropical storms, areas Down East are extremely vulnerable to storm surge, which can bring not just water but also salt. Storm surge is a big component of how salt gets delivered to the system.

So is drought, which is a very confusing problem to explain to people, she said. Salt can penetrate the ground when it’s arid and when it’s extremely wet, and both are a risk for saltwater intrusion.

“We focus a lot of attention on hurricanes because they’re acute. But what we’re looking at with ghost forests is kind of more of a slow disaster. Those hurricanes might push you over the edge, but it’s a disaster that’s building over time as a result of the accumulation of salts in these exposed and vulnerable landscapes,” Bernhardt said.

Thermal expansion

Scientists have evidence that water levels are rising, another change affecting Down East now and in the long term.

“We’ve been measuring water level in many different ways, and yes, water levels are rising,” said North Carolina King Tides Project founder Dr. Christine Voss, a retired coastal scientist from University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences.

“Part of the whole sea level rise story is just the thermal expansion of water,” she continued.

Also affecting water levels are wind, the tides and the Gulf Stream.

Last year, federal agencies published a report saying that water levels are expected to rise within the next three decades, by 2050. “That difference for the East Coast is about 10 to 14 inches. And that’s kind of hard to comprehend,” said Voss.

King tides have always happened and are predictable, taking place when the moon is at its closest distance to the Earth, causing extremely high high tides, and extremely low low tides. “We use those high tide events to help us visualize what future higher sea levels will look like. It’s kind of giving us a glimpse of what future higher sea levels will look like,” Voss said.

In the last 20 years, sea levels have risen about 6 inches. Within the next 30, federal officials forecast sea levels up to a foot higher.

Voss said other visible changes are related. “We’re having more and stronger tropical storms,” and know that these will be stronger.”

One of the biggest take-home messages, Voss said during the gathering, is that the changing environmental conditions are basically integrated into the coastal landscape, “and I’ll say in your seascape as well. You are the communities seeing these changes. And there’s a lot of complexity,” she said, referring to the numerous changes happening at once, including warmer temperatures and sea level rise.

Katherine Arnade is co-leader of the Sunny Day Flooding Project, which aims to monitor how often land is flooded due to sea level rise. Project scientists are measuring water levels and storm drains using special gauges they have developed. The sensors also take photos of the roadway and can measure flow in stormwater systems, including the contributions from rainfall and, in some cases, groundwater. The first installation was in Beaufort in 2021.

“We’re committed to learning about flooding in Down East and collecting data that’s useful to your community for as long as long as we can,” Arnade said, adding the sensors will be there for at least five years. Right now, there are only four sensors in use but the program could expand.

Realtime sensor data is available online.

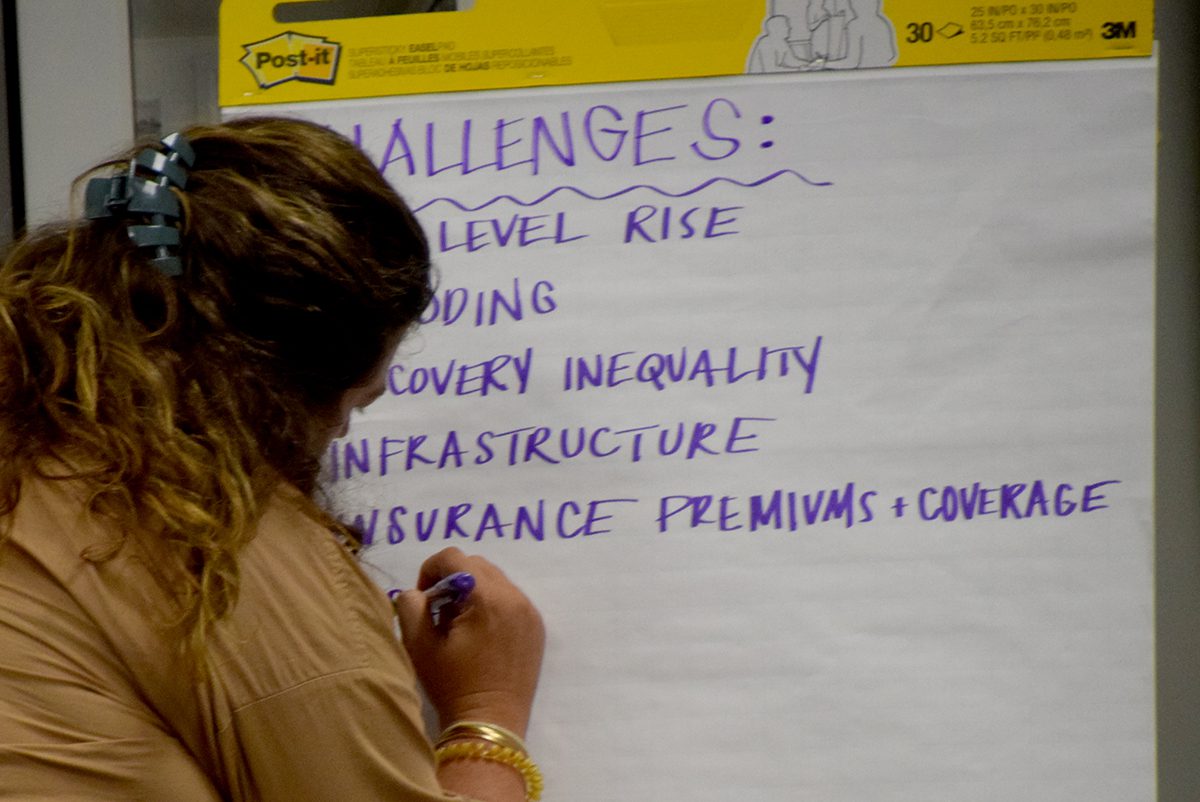

Priorities identified

Dr. Rob Young, a geology professor and director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University, has been part of the Down East Resilience Network since its inception three years ago. Young recently worked with Cape Lookout National Seashore officials to assess its villages’ and historic buildings’ vulnerability and has piloted a program for vulnerability assessments of private homes Down East.

“I can’t tell you how many times in the last 24 hours I’ve had people come up to me frustrated with the nature of the new development that’s going on Down East, where folks are filling wetlands, building in places where we know that septic systems cannot possibly be perking,” he said the second day of the conversation.

Young said residents are frustrated. These folks who are generally suspicious of regulations, always seem to be regulated, while they see others not be held to the same standards. And elected county officials – the only local government representation residents of unincorporated Down East hamlets have – and county management were absent, despite being invited to the event.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the people who might answer some of those questions for us at the county level are not with us for these two days to help us find solutions or have that discussion. I don’t know how to fix that either,” Young said.

Young said his priorities are how to keep residents from being displaced by flooding, how transportation infrastructure and utilities will be maintained in the future, and how to deal with the public health implications of failing water treatment and septic systems.

“The final piece to all of this, I think, is trying to understand how we tap into some of those infrastructure dollars that have become available over the last couple of years that just don’t seem to make their way Down East,” Young said. “How can we tap into all of the new sources of funding available from the federal government that comes to the state and find a way to get some of those funds into a place like Down East, for meaningful projects? That’s what we really need to know, at the end of the day, from a meeting like this. We have to stop talking and start doing stuff. And we need our elected officials to really engage and help make that happen.”

Next: What is being done to prepare?