This report has been updated to remove the trademarked product name referenced in the study, which is not the device shown in the photo.

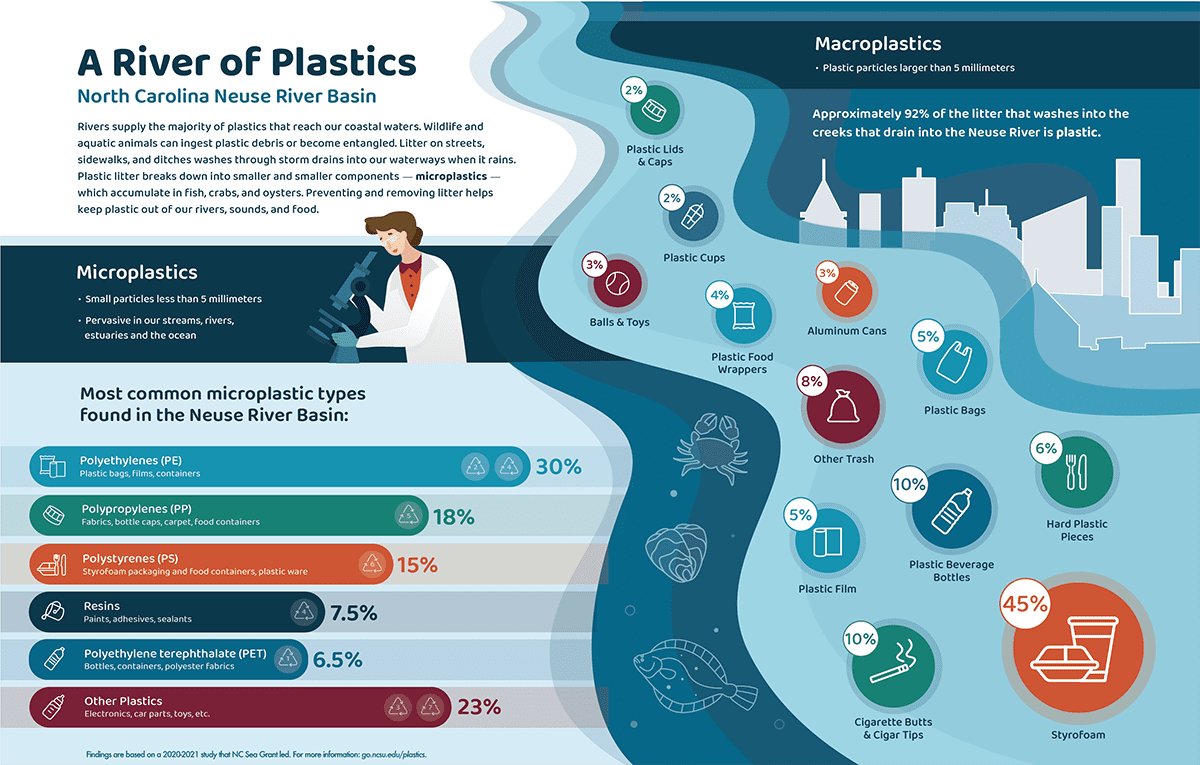

A recent study estimates that 230 billion tiny pieces of plastic the thickness of a human hair and 670 million microplastics about than the size of a grain of sand flow into the Pamlico Sound from the Neuse River Basin each year.

Supporter Spotlight

To reach that estimate, North Carolina State University and North Carolina Sea Grant researchers sampled 15 freshwater locations between Wake County to Craven County from August 2020 to July 2021.

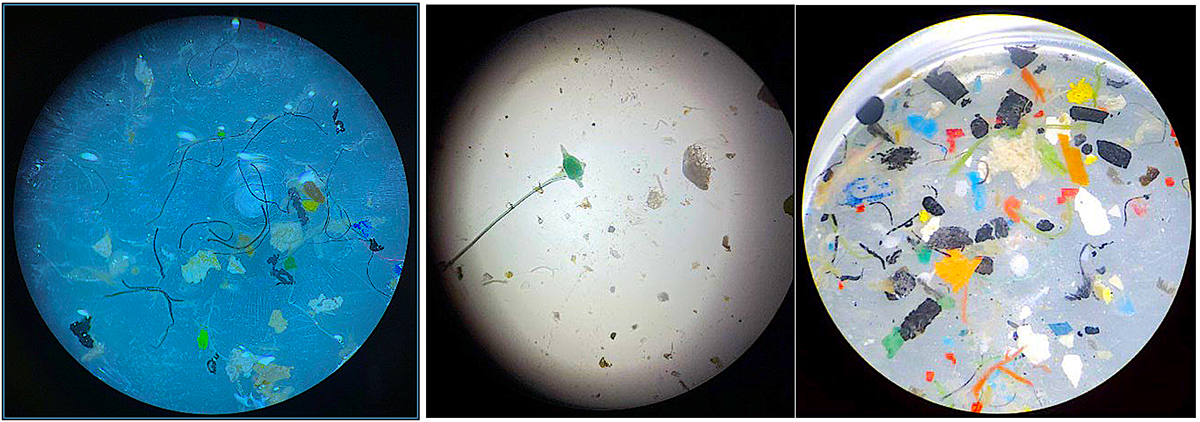

The presence of microplastics, which are less than a fifth of an inch, were found at all 15 sites, though the concentration varied depending on location, according to the research funded by National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration Marine Debris Program and North Carolina Sea Grant. The most common microplastics detected were polyethylene and polystyrene.

“This study effort completed the first sampling of microplastics (smaller than 5 mm) for North Carolina freshwater rivers and streams,” states, “Engaging Partners to Evaluate Plastics Loading to the Pamlico Sound from Urban and Rural Lands via the Neuse River in North Carolina,” the study published earlier this year.

Microplastics come in a variety of shapes such as fibers, fragments, pellets, spheres, flakes, foams and films, and originate from point and nonpoint sources including wastewater, industrial processes, tire wear, and degraded plastic bags, bottles, food containers and other discarded plastics.

The primary goal of this study is taking “the first step in characterizing and quantifying the annual loading of plastic pollution to our coastal waters from inland sources by examining contributions through the Neuse River watershed to the Pamlico Sound. The secondary goal was to use research results to raise awareness of plastic pollution since quantifying the scale of the problem in a local context has been shown to increase stakeholder engagement and interest,” according to the research.

Supporter Spotlight

The Neuse basin is home to over 2.5 million people, mostly concentrated in the highly developed upper watershed, while the lower watershed is mostly agricultural and forested land uses. Sample locations were selected to include a range of drainage area sizes, a variety of land uses, and to encompass locations throughout the basin, the research notes.

The highest number of all microplastics were observed in urban streams. “There was a significant correlation between streamflow and MP concentration in the most urbanized locations,” the study states. The study refers to microplastics as MPs.

The authors of the study, North Carolina Sea Grant extension specialists Dr. Barbara Doll and Gloria Putnam, and NC State Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering research scholar, Jack Kurki-Fox, shared highlights of their research in the article, “A River of Plastics,” in the summer edition of Coastwatch, North Carolina Sea Grant’s quarterly publication.

“Our study was the first to sample microplastics in North Carolina’s freshwater rivers and streams, focusing on 15 locations throughout the Neuse River Basin, from Wake County to Craven County. We evaluated the presence of microplastic particles by trawling for several minutes using a net with 335-micron openings (about the size of a small grain of sand) and by bailing 100 liters (about 26.4 gallons) of water through a 64-micron mesh opening (roughly the thickness of a human hair),” they wrote in the Coastwatch article.

“We estimate that about 670 million microplastic particles larger than 335 microns enter the Pamlico Sound from the Neuse River Basin each year. For microplastics larger than 64 microns, that estimate is about 230 billion particles per year,” the article continues.

Researchers sampled for macroplastics, as well, according to the study. They used three different methods in the upper portion of the river basins. They regularly collected trash at seven streams, captured debris during stormflow at two highly urbanized streams using a trap device and visually counted floating trash during stormflow events at two large tributaries and at one small highly urban stream in Raleigh, according to the research.

All three macroplastic sampling methods show that the bulk of trash washing into streams is plastics.

“Floating trash was nearly all plastics and plastics also dominated the litter captured during storm flow using the trash collection boom and basket (96%). Styrofoam pieces were the most common litter type observed using these two sampling methods,” the study states. “Grid samples in contrast contained a more diverse trash profile with plastics comprising about 74% of all samples collected.”

Urban streams were found to produce much higher counts of trash and macroplastics. The study’s findings indicate that plastics are commonly transported downstream during high flows and are likely flowing into the mainstem of the Neuse River where it will continue to wash into the Pamlico Sound.

“Therefore,” the executive summary concludes, that “programs to prevent this litter from being deposited on the ground and washed into the stormdrain system are critical to plastics from entering stormwater systems in urban areas and being transported to downstream rivers and estuaries of critical social, economic and environmental importance.”

“Most of us don’t witness the ‘plastic flows’ in our state because we aren’t out during storm events,” Putnum told Coastal Review.

“But our trash traps and the visual assessments of floating trash we conducted during high stream flows, show there is a large quantity of plastic, especially plastic bottles and foam pieces, moving through some of our urban streams,” she continued. “Next, we need to identify where it ends up and move toward prevention, because removing it once it’s in the water is costly and extremely challenging.”

Doll, who also is on the faculty for the NC State Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, told Coastal Review that, in a way, it was not surprising they found microplastics in all of their samples, and found strong links between the macroplastics and the microplastics.

“Polystyrene, polyethylene these were really common microplastics and lo and behold, very close to the items that we were finding in our trash collection research component as well,” she said.

Doll explained that she has long history with freshwater streams and has worked on nonpoint source pollution and stream improvement for all her career, and “trash has always been at the forefront of my concern from childhood.”

After hearing about the funding through Sea Grant to work on marine debris and plastics, Doll said they decided to take advantage of the funding opportunity.

Because of her work conducting stream morphology assessments, or collecting data on streams, she said she sees in the urban areas “a lot of garbage and it’s pretty disheartening.”

She was also hearing more about the issue of microplastics. She mentioned international articles about researchers looking at pollutant loading into the ocean from riverine systems.

“I believe it,” she said about what she had been reading, “because of all of the garbage I see in just our small creeks, and these creeks are connecting to bigger waterways and into the main river, and then that’s going to go into our estuary. And in some cases, like the Cape Fear, dump right out into the ocean.”

Between the amount of trash she was finding while out in the field and the recent attention on microplastics, it made her ask, “How do we get a handle on that? We had not heard of any type of this work looking at trash and plastics — microplastics and riverine systems — reaching coastal waters in our state.”

Doll said that she anticipates a push to regulate debris in waterways. If that’s the case, there needs to be research on how to quantify the debris, how to prevent it, determine what the real scale is, and “Would this be the right thing to do, to require cities and counties to clean up?” Doll said. These questions are important, and the funding seemed like a real opportunity to jump in to get answers, data and experience.

“We were very interested in this topic,” she said, and since there’s a lot of questions “let’s just start to take a bite out of that, and here’s some funding that could help us.”

Doll said the team had to adapt early to some obstacles when they began collecting samples. One was the amount of organic material they had to sort through.

“This was our biggest challenge. We spent several months, maybe almost a year, dealing with the amount of organic matter that had to be digested, filtered out, removed, separated, so we could quantify these plastics,” Doll explained, adding that the Plastics Ocean Project Executive Director Bonnie Monteleone and her team separated the plastics from the debris in their laboratory in Wilmington.

Once that was resolved, they had a solid procedure for getting that separated and identifying the plastics.

Another challenge that was surprising, Doll noted, is that when these plastics break down and degrade in the environment, it changes the plastic’s chemical signature, but the databases they were using to identify what kind of plastics they were finding were based on pristine plastic. “That became a big challenge as well,” she said, because some samples would give a signature of a food additive, but they were actually degraded plastics.

Capturing the trash during storm flow also took some adapting. The first net they put across a stream to catch trash, collected, leaves, pine straw and sticks, and ultimately failed.

“We had to kind of research about different trash-capturing devices and found some people that have been doing work in that,” including the litter getter trash trap.

During the project, Doll said they learned so much about the sampling techniques that now they can share that information with municipalities and others on how to monitor for microplastics, macroplastics, or general marine debris.

“We’ve learned a lot, and I think that that’s really important to moving ahead in the future, where we really start to grapple with this serious issue. We found very high levels of trash and microplastics from the urban areas, and that increases with higher levels of storm flow,” Doll said. “That says that those are the areas we really need to target to reduce this contribution in our particular rivers and sounds here in North Carolina. We need good strategies, and good tools and practices and to be consistent.”