To say Pungo Lake is off the beaten path would be a generous understatement.

Situated in the northeastern part of North Carolina that all major roads avoid and even Google doesn’t update, any attempt to travel there brings the possibility for adventure or the potential for mishap.

Supporter Spotlight

“Make sure you’re gassed up (with) at least half a tank of fuel, because you’re a long ways away from gas stations,” advised Wendy Stanton, refuge manager for Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, in which Pungo Lake is situated.

Access from the south or west puts travelers on N.C. Highway 45, N.C. 99 or both, since the roads run together for a stretch. Coming from the north or east, the most direct routes involve a variety of tiny roads and then what should be a straight shot on several miles of unpaved, single-car-width peat lanes. But these often end up being closed, either to protect wildlife or to protect the roadways’ accessibility for refuge maintenance vehicles. Google Maps does not reflect these closures, and cell phone service is spotty to nonexistent on the refuge.

When they’re open, in ideal conditions, “driving on them is basically driving on a dry crust of peat,” Stanton said. But traffic breaks down the peat’s structural integrity, as does rainfall, turning the roadways into “mucky slurry” that is unsafe for motorists.

“Last winter, we had to close all our refuge roads because they were in such bad shape,” she said.

Peat is a very fine, organic soil formed from fallen leaves and branches that remain on the ground in an anaerobic (without oxygen) environment, she explained. “When it’s dry, it’s almost the same consistency as corn starch.”

Supporter Spotlight

Scientists think the refuge landscape, pockmarked by lakes now, was once contiguous peatlands that wildfires burned down in places, forming lakes as rainfall accumulated there, Stanton said.

“We think Pungo Lake was formed by a groundfire …When those peat soils ignite, they can just burn and smolder for a long period of time.”

Nearby, Phelps Lake, as well as New Lake and Lake Mattamuskeet, each are thought to have formed in that same way. Those lakes, and Pungo Lake, too, are all on North Carolina’s large Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula.

Pungo Lake is a “blackwater lake” with very little to no sunlight penetration, due to the “tannins from the peat and the vegetation, and particulates from the peat soil,” Stanton said. That means there is no submerged aquatic vegetation growing in it, and the lake — with holes up to 6 feet deep in places — looks deeper everywhere than it is, she explained. Swimming, boating and fishing on the lake are always prohibited because “the focus of Pungo Lake is inviolate sanctuary” for wildlife.

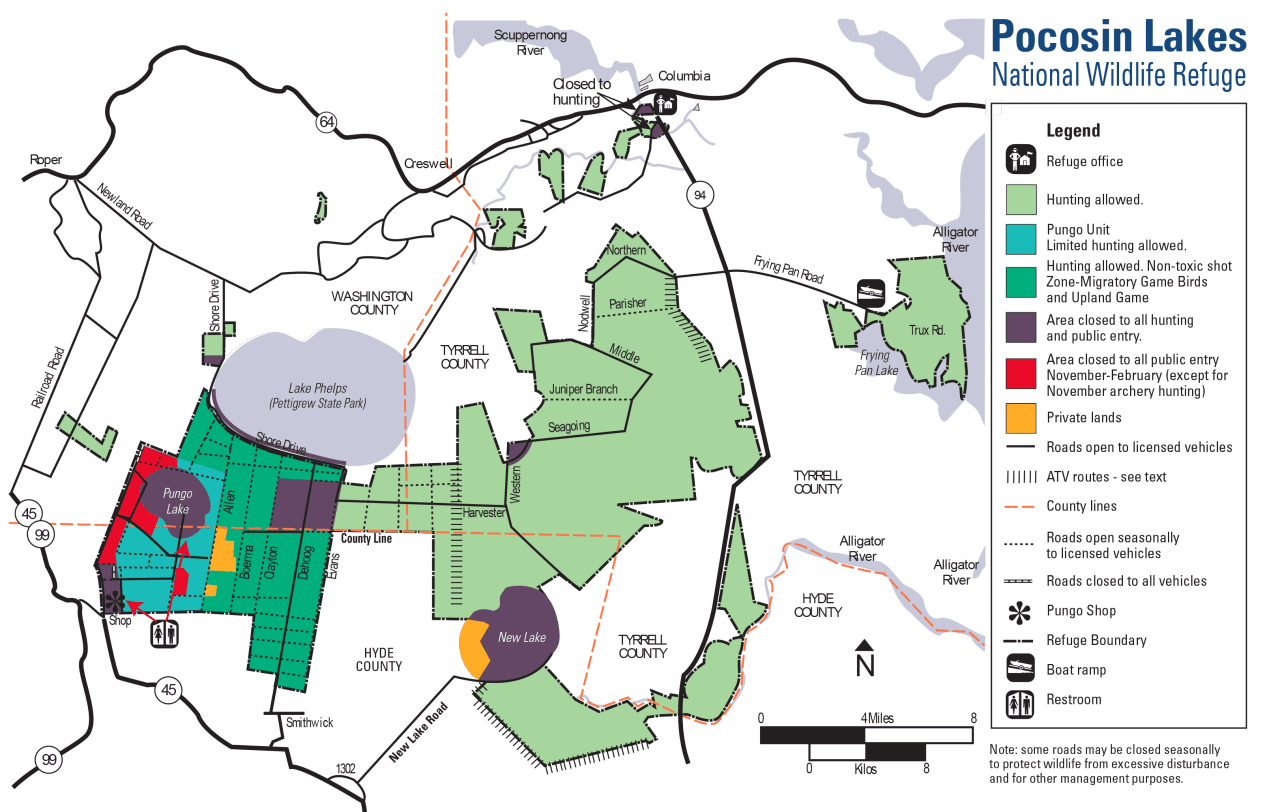

The nearly 2,800-square-acre lake is the centerpiece of the refuge’s 12,000-acre Pungo Unit, which was first established as a national wildlife refuge in the 1960s. The rest of the land that now constitutes Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge was added in the 1990s; so currently, the refuge spans over 100,000 acres in Washington, Hyde and Tyrrell counties, according to the refuge website.

A refuge map shows its piecemeal sections spread over the large geographical area.

The refuge’s easternmost swath is by the western bank of the Alligator River, while small areas just south of Columbia include the refuge office. The Pungo Unit is almost the westernmost reach; just one small section of refuge lies even further to the west.

Southeast of Pungo Lake, a larger body of water mostly included in the refuge, New Lake, has been so named since at least 1998, when Stanton began working for the refuge as a biologist. It’s still mislabeled as Alligator Lake on Google Maps.

The refuge owns about 85%, or 4,500 acres, of that roughly 4,900-acre-lake, she said, with the remainder privately owned.

North of Pungo Lake, the refuge includes about 4 miles of shoreline around Lake Phelps’ perimeter, so refuge staff works closely on projects with Pettigrew State Park, which includes Lake Phelps, Stanton said.

While all three lakes are rainwater lakes, their waters are each strikingly different colors because of the soil types beneath them. Lake Phelps appears clear to blue-hued, Pungo Lake is blackwater and New Lake appears brown due to its mixture of peat and mineral soils, she said.

Even not being the farthermost reaches of the refuge, traveling just from the refuge office to the Pungo Unit takes 50 minutes, Stanton said. The only facilities on the refuge, apart from the volunteer-staffed visitor center, are two porta-potties. She encourages visitors to bring water and to be mindful of the weather.

Most of the year, Pungo Lake and the surrounding refuge are quiet, almost seeming otherworldly. No rush of passing traffic or other human-related noises exists to overrun the occasional birds’ calls or the steady thrum of insects.

Early one July morning, the contents of three overturned trash cans were spread across both lanes of Shore Drive, which is included in the refuge and runs just south of Lake Phelps. There had been no overnight storm or significant wind. Turning onto Allen Road, which leads to Pungo Lake (about 6 miles to the south), a plausible explanation appears: A big black bear lumbers off the peat roadway into the bushes.

The Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula has the largest recorded black bears and the highest black bear population densities in the world, according to the nonprofit North Carolina Wildlife Federation.

Many people visit the refuge specifically to see black bears, according to Stanton.

Plymouth, the most populated town on the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula and about half an hour’s drive northwest of the Pungo Unit, hosts an annual black bear festival in June to celebrate its famous residents.

A 2003 black bear population estimate based on collected hair samples found 3.5 black bears per square mile, meaning between 300 and 400 bears lived on the refuge, Stanton said.

The bears of Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge were found to have the highest genetic diversity in their population out of three regional refuges, meaning “that population is more adaptable to change,” she said. The next-highest genetic diversity was found at the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, located to the northeast, also on the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula, and which is connected to Pocosin Lakes by a “wildlife corridor.”

The lowest genetic diversity was found in the black bear population of the Great Dismal Swamp Natural Wildlife Refuge in Virginia, which “makes sense because of all the development going on around it,” she said.

Two decades later, a new black bear population study is in the works for northeastern North Carolina. “Genetic technology has expanded in the last 20 years,” Stanton said. “I’m excited to see that study.”

Other year-round refuge residents are also numerous, including whitetail deer, beavers, muskrats, nutria, otters, marsh birds, wood ducks, hawks, owls, bobcats, foxes, red wolves, turtles, frogs, toads, salamanders, snakes, alligators and more.

“I consider it ‘the Yellowstone of the East,’ too, with the diversity of species,” Stanton said of the refuge, borrowing phrasing from one of her friends.

The only sound first thing on a July morning is the aggressive bumping of huge horseflies into the parked car’s windshield. The roadway is closed immediately ahead. A beaver scuttles across the road into a ditch, quickly disappearing from sight.

About a quarter-mile west of the chained-off Allen Road, turning from Shore Drive onto F2 Road, a longer stretch is drivable before a metal gate comes into view, closed and locked, with posted signs announcing the road’s closure to vehicles. Turning around reveals curious wild turkeys, one creeping out first to check the surroundings and apparently giving its nod of approval to another, who then ventures out. The turkeys run down the road together.

Rabbits and quail are well-camouflaged among refuge flora, which includes wildflowers, grasses and ferns. Honeysuckle and wild grapevines dangle from trees and bushes overhead. A combination of high humidity and the smoke from Canadian wildfires obscures everything more than a short distance away in haze.

Each year from about November through January, the refuge gets naturally louder as more than 100,000 migrating swans, geese, ducks and other birds convene annually to rest and recharge before continuing south. For over 20 migratory species — including ducks, tundra swans and snow geese — the refuge is more than a stopover: It’s their winter retreat, according to the refuge website.

With “very minimal human disturbance” and proximity to fresh water and waterfowl impoundments — designed to grow native plants for the birds’ consumption — Pungo Lake provides an ideal sanctuary for migratory waterfowl, Stanton said. In the winter, “amazing flyouts” take place around sunrise when the birds leave to go forage, and then again at sunset as they return to the lake at night.

Over 30,000 people annually visit Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, which is about a 5,000-person annual increase since before the COVID-19 pandemic.

But Stanton maintains even the 30,000 reflects “a real underestimate.” She said there is sometimes bumper-to-bumper traffic in the winter when people flock to see the waterfowl, which settle on all area lakes.

Landowners’ objectives before the refuge was established were different, Stanton noted.

While nearby areas boast rich soil and productive farmland, peat is a “nutrient and mineral poor soil” that people unsuccessfully tried to farm in the past, she said. Much of northeastern North Carolina’s pocosin land — “pocosin” is a Native American word for “swamp on a hill” — was ditched and drained, with numerous canals dug by hand by enslaved people, such as those around Lake Phelps and Lake Mattamuskeet.

Stanton thinks the area near Pungo Lake was ditched and drained with “old, heavy equipment” more recently, closer to the 1960s, to access a valuable commodity — white cedar wood. For a time, she said the land was also mined for the alternative fuel source, ethanol.

“Now we recognize the value of healthy pocosin land,” Stanton said. Pocosin is also called “Southeast shrub bog” and provides “tremendous carbon storage…(and) excellent wildlife habitat.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manages the refuge with main goals of providing quality wildlife habitat, reducing the risk of catastrophic wildfire and preserving the “tremendous water quality benefit,” she said.

Wet peat ensures a higher water quality for the surrounding area as it reduces both catastrophic fire and flood risks, she explained. Over the years as the refuge has received funding, it has installed water control infrastructure designed to rewet the peat.

“We have now restored over 37,000 acres of pocosin habitat,” she noted, and the goal is to add more water control infrastructure to keep water in the peat in an additional 7,000 to 8,000 acres.

This is one of the largest hydrology restoration projects in the country, according to www.fws.gov.

“Just over the years as we received funding, we piecemealed that infrastructure in to start rewetting the peat,” she said.

The refuge drafted a water management plan, which it put out for public review in 2020, and Stanton said that plan is still being finalized.

The refuge’s visitor center, the Walter B. Jones Sr. Center for the Sounds, is located at 205 South Ludington Drive in Columbia. Free, public programs take place there regularly, as well as at the Red Wolf Center, located a mile south of Columbia on N.C. Highway 94.

For more information about either the visitor center or the red wolf programs, call 252-796-3004 or visit the refuge website at www.fws.gov/refuge/pocosin-lakes. For updates on road closures, call 252-796-3004, extension 225.