Four miles before the eastern end of U.S. Highway 70, there is a right turn that brings travelers across a small bridge and into the town of Beaufort, North Carolina.

Beaufort is humming with activity in all months of the year, whether with government business near the 115-year-old Carteret County courthouse or tourist activity closer to the waterfront. The town has nearly as many restaurants and museums as it has accolades from national magazines.

Sponsor Spotlight

But for much of its history, Beaufort was almost forgotten. It was a small outpost that represented a bypassed hope for the future of North Carolina. Over the span of a century, Beaufort has turned itself into a center for history, water activities, and environmental study. It has gone on a long journey to become one of the most memorable places on the North Carolina coast.

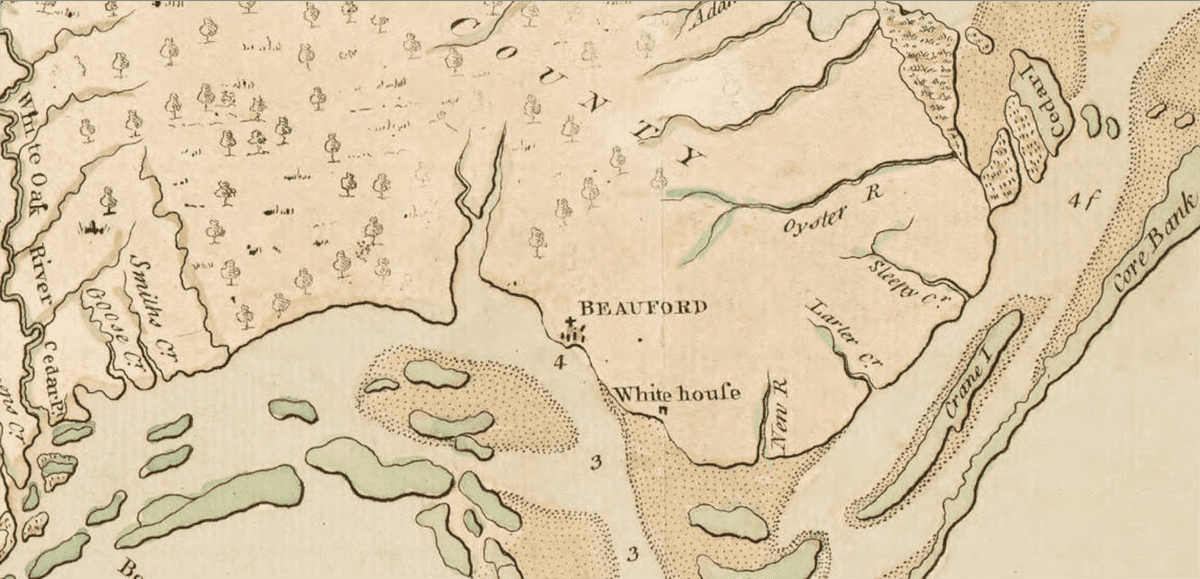

Beaufort was laid out in 1713 and incorporated in 1723, making it the fourth oldest town in North Carolina. It was part of the English attempt to turn North Carolina into a productive colony. Beaufort was founded near Beaufort Inlet, one of the few longstanding ocean inlets along the Outer Banks. Given the primacy of water transportation at the time, the hope was that ocean-going traffic through Beaufort Inlet would help bring North Carolina the prosperity that Virginia was experiencing at the time through its wide, deep Chesapeake Bay.

Unlike two of the first four towns, Edenton and New Bern, Beaufort remained isolated throughout its first several decades. Edenton was the colonial capital for several decades and close to Tidewater Virginia, while New Bern benefitted from substantial growth in the Neuse and Trent River basins. Beaufort remained isolated, like the original town of Bath, and did not attract settlement to the mainland area of Carteret County. Consequently, the town only had a few dozen people in 1765, according to a French traveler’s account cited in the downtown district’s nomination form to the National Register of Historic Places.

Even after Beaufort grew to a few hundred residents by the first census in 1790, Carteret County was the state’s second-least-populated county in that census and remained one of the 10 smallest for decades. Beaufort also was not as defined by plantation slavery as the other larger, early towns. Despite the lesser reliance on large cotton or tobacco plantations, enslaved people still worked in agriculture and in maritime professions throughout the town and the coastal area of Carteret County.

Sponsor Spotlight

Despite its small size, Beaufort had several resident political leaders. These included Otway Burns, the famed privateer of the War of 1812, and revolutionary leader William Thompson. Some of these leaders were interred in the Old Burying Ground, one of the state’s oldest cemeteries. According to land records, the earliest potential burial at this Beaufort graveyard dates to 1724. There are dozens of stories about its most notable graves, from the British officer buried standing up (and facing England) to the little girl buried in a barrel of rum.

Another early heritage of Beaufort is its historic houses. The housing landscape in Beaufort today stretches back to the late 18th century. There was once a theory that one of the oldest houses in town, the Hammock House, was built in the early 18th century and was even visited by Blackbeard. Despite its popularity among locals and mid-20th-century writers, this theory is almost certainly false. It would have been difficult for residents so far from centers of commerce and industry to have brought together the materials and expertise to build such a substantial home in the 1710s. Instead, Beaufort’s earliest standing houses were likely built around the 1780s, which still ranks them as some of the oldest in the state.

Beaufort was only of nominal strategic importance during the Civil War. Beaufort Inlet never grew to the size and depth that the town would have required to become a major port. The Union captured the town early in 1862 after subduing nearby Fort Macon and held it for the rest of the war. There were no substantial battles to rival those in important towns like Wilmington, New Bern, or even Plymouth, where the Confederates secured arguably their greatest North Carolina victory in 1864. Instead, Beaufort was taken with almost no effort.

The 20th century was defined by two developments that continue to shape the town to the present day. One was the growth of industry. Beaufort counted a number of businesses by 1916 including two manufacturing plants, two banks, nine building contractors, and eighteen grocers.

The study of marine biology also brought experts and attention to the town. One of the nation’s first centers for the study of marine biology was opened in the Gibbs House by Johns Hopkins in 1880. The Johns Hopkins Seaside Laboratory eventually helped prompt the foundation of the numerous marine labs currently located on Pivers Island, including a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration facility and the Duke University Marine Lab.

The other major development of the past century, of course, was tourism. With the railroad’s arrival in 1906, travelers began to see the benefits of the quaint coastal town. Beaufort also benefited from having been small throughout the 19th century. Unlike more developed towns such as Elizabeth City or Wilmington, limited growth meant that the town kept its original cityscape. While the town began adding hotels, restaurants, and marinas in the 20th century, it retained its 18th-century homes and street grid. A 1988 report in the New York Times noted, “though surrounded today by modern shipping facilities and undistinguished commercial development, the heart of Beaufort has changed little since it was laid out in 1713.”

One of the legacies of tourism’s impact in the town is its keen interest in historic preservation. It is an attractive place for new homeowners to move in, restore old houses, and showcase those houses to the greater community.

One of these homeowners is Eric Lindstrom, who recently finished renovating the 18th century Piver House on Ann Street.

Lindstrom had worked on historical rehabs in Fayetteville for many years and had been on the lookout for a historic home project before settling on Beaufort. Lindstrom said that the biggest challenge to this renovation was not material or labor but time.

“The work takes a long time and we wanted to do it right,” he said.

The project included some modernization but also a strenuous effort to retain original material such as period-appropriate windows. With the renovation, Lindstrom joined a community of other historic homeowners in Beaufort who share tips and open up their homes for the Beaufort Historical Association’s annual Old Homes Tour.

Today, Beaufort could be viewed as an economic success story. As of June, it had 21 restaurants, one of the highest totals for any North Carolina town with fewer than 5,000 permanent residents.

Beaufort was voted America’s Coolest Small Town in 2012 and has been featured on HGTV and other television channels. It has also started to work harder to acknowledge its African American history with attention to historic Purvis Church and a regular African American bus history tour.

The town is 7 miles from the nearest beach and yet has the kind of summer traffic that sand-adjacent towns often enjoy.

Beaufort stayed mostly the same for over 100 years, but a combination of economic development, tourist attention, and rising sea levels have made change a reality. Now, Beaufort looks to move beyond its small-town identity as it grapples with this newfound importance in its fourth century of incorporation.