Though millions of people would qualify for drinking water protections under a nationwide proposal to limit certain chemical compounds in water sources, millions more would not, a new study concludes.

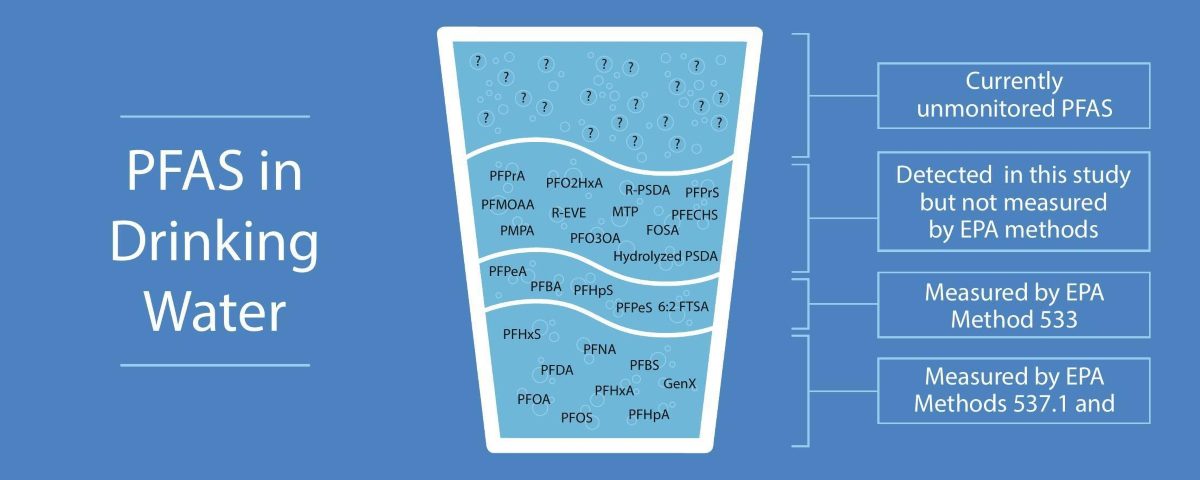

Nearly half of the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, found in drinking water samples collected across 16 states, including North Carolina, are not monitored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, according to the peer-reviewed study by Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit international environmental advocacy group.

Supporter Spotlight

In the community-led pilot study published in the Science of the Total Environment, commercial global laboratory Eurofins Regulatory Science Services tested for 70 PFAS. That’s 41 additional PFAS that are not covered by the EPA’s test methods.

Of 44 samples collected from both public water sources and private wells, 30 were contaminated with PFAS.

“Every single one of those samples had a PFAS that was not monitored by the EPA methods,” said Anna Reade, Natural Resources Defense Council senior scientist.

Samples collected in North Carolina contained the highest levels of unmonitored PFAS.

The samples, taken in Ocean Isle Beach and Oak Island in Brunswick County, also contained the highest concentrations of PFAS, along with samples from Maine, Colorado and Texas.

Supporter Spotlight

Sixteen different types of PFAS were found in water collected in Ocean Isle Beach and 12 chemical compounds were in the water sample from Oak Island, Reade said.

Tap water tested from Brunswick County came from the county’s northwest treatment plant, which is sourced by the Cape Fear River.

For nearly 40 years, a chemical manufacturing plant nearly 80 miles upstream of Wilmington discharged PFAS directly into the river. The river is the drinking water source for tens of thousands of residents.

The company responsible, Chemours, is under a consent order to meet a host of compliances to reduce the amount of PFAS discharged from its Fayetteville Works facility in Bladen County.

A thermal oxidizer has been installed at the plant to capture more than 99% of PFAS from being emitted into the air. The company also plans to build an underground barrier wall on-site to stop PFAS, including GenX, a chemical compound specific to the Fayetteville Works plant, from traveling through the ground into the river.

The EPA is proposing to set limits on GenX and five other PFAS in public water systems. The agency’s proposal includes limiting the chemical compound in combination with three other PFAS: Perfluorononanoic acid, or PFNA, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid, or PFHxS, and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid, or PFBS.

The agency also is proposing to set maximum contaminant levels, or MCLs, on perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, and Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, or PFOS, at 4 parts-per-trillion, or ppt.

Natural Resources Defense Council’s study found that out of the 30 drinking water samples that contained PFAS, 15 would exceed the EPA’s proposed contamination limits.

The proposed maximum contaminant levels are a big set forward, Reade said, one that, according to EPA estimates, would qualify between 70 and 90 million people for drinking water protections.

“But our study shows that there will be communities that will be left behind because, as industry adapts and changes to the regulatory environment, they’re going to use different PFAS that are unmonitored, unregulated and there’s no way that the science and regulatory community can keep up,” she said.

According to information provided in the study, there are around 14,000 PFAS. To expect the EPA to study each individual chemical, its potential associated health effects, and establish drinking water standards for each could not be done in several generations’ time, Reade said.

Under the EPA’s proposed rules, expected to be finalized later this year, public water providers would be required to monitor for the six PFAS and report the results of sampling to the public if levels exceed the regulatory standards. Water utilities found to have one or more of the chemicals above the proposed limits would have to reduce the levels to meet the proposed limits.

EPA officials say that the anticipated benefits of establishing maximum contaminant levels on the six chemical compounds would lead to reduced cases of kidney cancer, strokes and heart attacks, and developmental effects in children, including low birth weight.

Reade said that there will likely be co-benefits for customers of public water providers who would have to upgrade their systems to meet the maximum contaminant levels.

“It will probably treat for a lot of other types of PFAS,” she said. “It will probably treat for disinfection of byproducts and pharmaceuticals.”

But the worry is that unmonitored PFAS, particularly newer, smaller ultra-short-chain substances, will likely slip through drinking water treatment if they’re not accounted for, she said.

These types of chemicals were the most prevalent found in the Natural Resources Defense Council study.

“That was really surprising for a lot of our community members and, to be honest, a bit surprising for us because it is not a well-monitored-for PFAS and we don’t have any studies on the health effect of being exposed to it, which is always a very hard thing to report back to people who are being exposed to a chemical,” Reade said.

An ultra-short-chain substance called perfluoropropionic acid, or PFPrA, was predominantly found at the highest concentration in samples submitted for the study.

Ultra-short-chain PFAS may be harder to capture through filtration systems because they’re so small, Reade said.

PFPrA was found in both samples from North Carolina.

“I think this (study) is just another data point highlighting the need to manage PFAS as a class,” Reade said. “North Carolina’s the prime example of why we need to do a class-based approach because we are not keeping up with the current exposure conditions for communities like yours.”

Clean Cape Fear stated in a release that residents of the Cape Fear region continue to be exposed to “dangerous daily doses” of PFAS, the potential health risks of which little are known.

“While the PFAS regulations proposed by EPA last month are a good start, we demand a whole-of-government approach to stop all PFAS exposures,” Clean Cape Fear Co-Founder Emily Donovan said in a release. “Our basic human rights are under attack. Communities like mine will no longer sit by as our children’s lives and our hopes for a healthy future are stolen by the greedy and irresponsible chemical industry.”

The study includes samples also taken from Alaska, Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Oregon and South Carolina.