A study recently published in Nature Climate Change found that the global food sector alone, the way it is now, could add nearly 1 degree Celsius to global climate warming by the year 2100. But over half of this anticipated warming could be avoided if there were simultaneous changes made to production and food waste systems, the energy sector, as well as universal diet changes.

It is exceedingly hard to estimate warming associated with agriculture at the global level. One of the biggest reasons for this is that the agricultural sector emits multiple climate pollutants, things like carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. Often, to make it easier to estimate emissions, a strategy is used called “carbon dioxide equivalents.” This puts all emissions on the same comparable scale, making it easier to measure aggregate impact.

Supporter Spotlight

The downside of this method is that different pollutants spend varying amounts of time in the atmosphere and trap different amounts of heat. So when you only look at these emissions through the lens of carbon dioxide, you risk blurring the picture of what agricultural emissions actually look like, and what can be done to address them. This study aimed to paint a clearer image.

Previous research has shown that one of the biggest pollutants from the agriculture sector is methane, which stays in the atmosphere for a far shorter amount of time than carbon dioxide but has a stronger warming effect on the atmosphere per mass. So looking at a long-term timescale in carbon dioxide equivalents would really downplay the role of methane emissions in the agriculture industry.

In order to get a better idea of how different pollutants could impact warming by the year 2100, the researchers had to look at the emissions individually, not as an aggregate.

“It just made it very apparent that when people are doing lifecycle assessments and when they’re doing this kind of work, the need to report those emissions in the explicit gas emission rather than an aggregate it is really essential,” said Catherine Ivanovich, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University and lead author on this study. “And the more that people can do this type of work can reduce future uncertainty.”

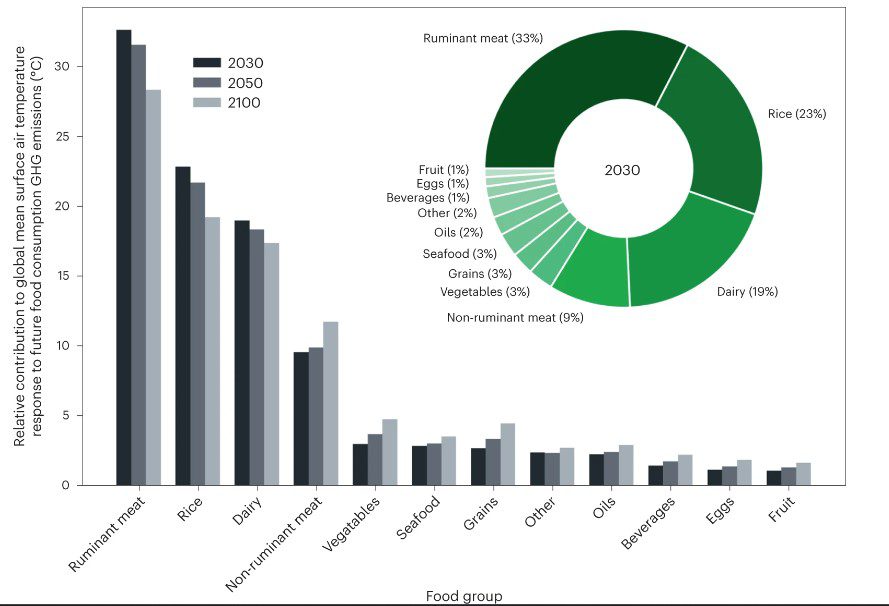

The researchers analyzed literature on the food sector including agriculture, fisheries, ranching and more. One of the findings of this study was that consumption of meat and dairy will be responsible for more than half of food-associated warming by the year 2030, and continuing through 2100.

Supporter Spotlight

The researchers explored four different possible arenas in which to mitigate anticipated warming: production, consumption, the energy sector and food loss/waste.

Optimizing agricultural production practices could contribute 25% of possible reductions by 2100. Decarbonizing the energy sector by 2050 would decrease the anticipated warming from the food sector by 17% by the end of the century.

A global diet shift based on health recommendations could decrease projected warming by 21%. Finally, if the world were able to cut consumer and retail food waste in half by the end of the century, it would decrease anticipated warming by 9%.

Changes to production, the energy sector and food loss/waste would all be largely structural or systemic changes, while changing the ways in which people consume food through diet is more of a behavioral shift. The limitation of this method is that making any kind of change on a global scale is very difficult and maybe unlikely. But the benefit is that taking a simplified approach allows people to see the full extent of what could be possible with these kinds of shifts.

“We can really just think of it as a very theoretical test of the rough magnitude these storyline scenarios might be expected to trigger,” Ivanovich said.

Regardless, Ivanovich says that both supply-side and consumer-side interventions, at multiple scales, are going to be critical to reduce anticipated warming in the food sector.

Questions about how to advance in the food sector are made even more complicated when moving beyond consideration of greenhouse gases. Other important factors to consider are how different food production techniques impact the environment and space use on the land and in the ocean.

“In order to make meaningful change in this sector, which is a really essential aspect of human life — supporting people, ensuring that we’re pursuing global food security and also sustaining economic livelihood for people who are producing our foods — we really need a multi-angle approach,” Ivanovich said. “We can really work towards increased food security, and providing people with nutritious diets, all the while working towards a more climate-safe future.”

According to the North Carolina Local Food Council, climate change poses a notable threat to the state’s food system. But a more resilient local food system focused on food waste recovery, local food infrastructure, better support for cultivators and addressing racial inequities in the food sector, among other things, would make the state less vulnerable in the face of pressures like climate change. There are resources on the Local Food Countil’s website toward that end.

There are also reasons to be optimistic, said Ivanovich. When you separate the different pollutants, you can see that nearly 60% of the warming by the end of the century is because of methane. And since methane is a short-lived emission, making rapid changes in that sector now could make a big difference in slowing down the rate of warming associated with the food sector.

It also underscores the urgency for action, according to Ivanovich.

“Everyone has to eat,” Ivanovich said. “We have to ensure that we can sustain our global population with nutritious food that supports people at a local scale. This is the problem that we can’t really shy away from.”