“The edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place.”

― Rachel Carson

Mine is a short journey, but you wouldn’t know it.

Hushed ripples as my paddle slips through the water are the only noise I make, but everyone else is making a racket. A cacophony of mingling bird calls, fish splashing as they wake up and bounce out of the water every which way. Sunrise is feeding time. I watch a big blue heron standing gracefully in the marsh and swiftly scarfing down a fish for breakfast.

Supporter Spotlight

The marsh looks like heaven when the rising sun begins to hit it and the colors of the sunrise reflect off the water. The marsh is my portable paradise, I take it with me wherever I go. When I need to get away from reality for a moment, which is happening more and more often now, I close my eyes and imagine my happy place. The sun on my face, the friends I make of the sea creatures, and the salty and sulphury scent I love because it smells like home. But more importantly, I imagine the journey to get there. It is a tranquility like no other.

If everything is going right, I am out of bed 10 or 15 minutes before the sunrise, and the ebbing tide is setting me up for success. I swing open the garage doors from the corner house on Gordon Street and snag my paddle, maybe my life jacket if I’m feeling like a rule follower.

Clad in a sun shirt and Chacos sandals with my bag of snacks that will soon be replaced with shells, I set out on my way — just a short, two-block jaunt down to the Beaufort waterfront where I find my yellow kayak in slot 10. The neighbors all draw sticks at the beginning of the season in hopes that they will receive a coveted kayak slip by the public dock on Front Street. This year, I was one of the lucky ones.

As the sun begins to peek out behind the clouds that cover the horizon, I heft the kayak off its rack and over to the water. Taylor’s Creek is its own paradise. I can’t wait to get out there.

In the span of just five minutes on the water I can wonder at bottlenose dolphins, a multitude of marine invertebrates (my favorites for their alien-like qualities!), and one of the best sunrises I’ve ever seen. And rarely are any other humans around. The minute my kayak hits the water, I am headed less than a quarter mile, directly across the creek. I want to be by the marsh, where the creatures live. Paddling parallel to the shore of the island, Town Marsh, I stick close to the shallows. There is a steep dip from the bank into the middle of the channel where a strong current may be ripping. I stay right on the edge, where I can peer over the side of my vessel to see what sea creatures are awake.

Supporter Spotlight

I pass over a sting ray, or maybe a skate. They camouflage so well, the only way they make themselves seen is from their outline, and the quick flap of the wings as they dart away once my paddle makes my presence known. There — right where the water laps onto the sand — what is it? I see two eye stalks and realize it is a blue crab buried in the sand. Sneaky. After paddling a few feet farther, I spot another. This must be a predatory technique. I wish I could stick around to see if any small fish will get caught in their sly claws, but the current is pushing me forward.

A loud scraping sound interrupts me from my trance. My head jerks away from staring at the water to look in front of me. I have mowed right into an oyster bed. Sweet! Now, just a little bit stuck, the perfect opportunity presents itself to check out what, or who, has made a home on this little reef.

These oyster structures are new in the past couple years. Taylor’s Creek is narrow, and at all times of the day, except sunrise, hundreds of boats go by. Their wakes can cause erosion of the marsh and the island.

Dr. Rachel Gittman, a researcher with East Carolina University, Brandon Puckett, former research coordinator with the North Carolina Coastal Reserve, and one of my professors from the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences, Dr. Niels Lindquist, came together to test living shoreline material intended to mitigate boat-wake impacts on the shoreline by restoring these oyster reefs.

My small kayak won’t produce a problematic wake, so I get up close and benefit from exploring what is living on the structures! First, seaweed is all I see, but then I see one of my favorite marine inverts. A purple spiny sea urchin! I gently peel one off the substrate, having to manually pry its suctioned tube feet off, so I can get a good look at its underside.

These urchins are not so spiky that they will stab me, as long as I hold them carefully and with taut hands. Cupping its spines, I check out my favorite part of this creature’s anatomy, the Aristotle’s lantern. Five opalescent, sharp, teeth-like protrusions face me. They gape out of a small black hole. Gooey, tiny tube feet wiggle around surrounding the moving teeth. Only a couple centimeters wide, the mouth captures my attention. Obviously, this is something special if it has garnered such a whimsical name. The urchin’s intricate shape and formidable appearance could convince me this creature terrifies its prey.

I frighten myself imaging an urchin 100 times its normal size. Luckily, these globular, spiny echinoderms stick with tiny prey, munching on seaweed, scraping algae, or catching plankton drifting by. Opportunistic omnivores … nothing to be afraid of — unless you range on the side of microscopic body sizes.

I paddle on and see a small shark fin rise in front of me. It must be chasing that school of fish I just glided over. The sun is higher in the sky now and it is almost low tide. Depending on the tides, I could make it to my destination by water only. However, I find more joy from beaching my kayak and tramping across the island. I pull up to the sign that introduces visitors, “Welcome to the Rachel Carson Reserve,” and make sure to pull my kayak up farther on land since I will come back to it at a higher tide. I can’t let my ride float away without me! Grabbing my bag, I look back at Beaufort and turn toward the trail that will lead me into a landscape that calms my whole being.

The gratitude I experience for having the opportunity to be here, early on a Sunday morning in the middle of the fall semester, is beyond measure. You can’t have happiness without first knowing how to be grateful. This space I am in allows me to take clear deep breaths. No one is around telling me what to do, there is no one to care for, no work to be done. It is too early for friends or family to even be awake to interrupt my reverie with the vibration of an incoming text. And this is still just the journey! Pure bliss. The destination awaits.

Scampering across a sandy patch, I find my way to what I’ve deemed my secret trail. It is a bit hidden behind some bushes, but once inside it is like Wonderland. There is a small trail lined by dense trees that open to a cleared, trampled circle. Here, I imagine, are where the wild horses of the reserve hang out to cool off or hide from tourists.

There is a mulberry tree here where I have harvested berries, just enough to sustain me, since I am sure they offer sustenance for the horses as well. I maneuver my way through the rest of the short, overgrown trail and come out on a hill. I can see the marsh, and my destination from here, but if I turn just 180 degrees, I see where I came.

There is Front Street, bustling a bit more as churchgoers and dog walkers start their mornings. I can still hear the honks of a car and the music from a passing boat. It is strange to feel like I am on an uninhabited island yet still hear the happenings of life in town. This is peaceful, I am alone, but not lonely. Just how I like it.

Trekking toward the western side of Town Marsh, I am stepping through dune marsh-elder, American beachgrass, pennywort, and mock strawberries. My favorite flower, which I will always associate with home, is the bright orange Indian blanket, resembling a sunflower. These wild plants mark my way to the path I head toward.

Hot and sweaty, I stop for a drink of water at another favorable lookout spot. I have the perfect vista of downtown Beaufort. Sunday morning is in full swing. I see tourists sitting on the porch at Dock House waiting on breakfast, while others are walking along the boardwalk. I continue on, smiling to myself, appreciative for the beautiful day and knowing I’m now sharing this time with others too.

Only 20 minutes after beaching my kayak, and maybe 30 after launching into the water, I have arrived. I stand at the rickety wooden sign that is painted green indicating Bird Shoal is ahead of me. I sigh and smile again. I’ve made it.

Excusing myself to the mud snails I bother as I walk through a bit of marsh at low tide, I continue over the dunes to the water. Here I have an undisturbed view of Beaufort Inlet, Fort Macon, and the sound side of Shackleford Banks. Blue sky and bluer water. This. This is my happy place.

In her book, “The Edge of the Sea,” Carson recounts her time at Bird Shoal when “in calm weather, one is able to wade out from the sand-dune rim over immense areas of the shoal, in water so shallow and so glassy clear that every detail of the bottom lies revealed.” (pg. 99-100) She captures the view so vividly. I’ve explored North Carolina’s coast, far and wide, and at low tide on a sunny day, Bird Shoal has by far, the clearest, bluest water I’ve seen in this coastal state. I crave wading through those waters.

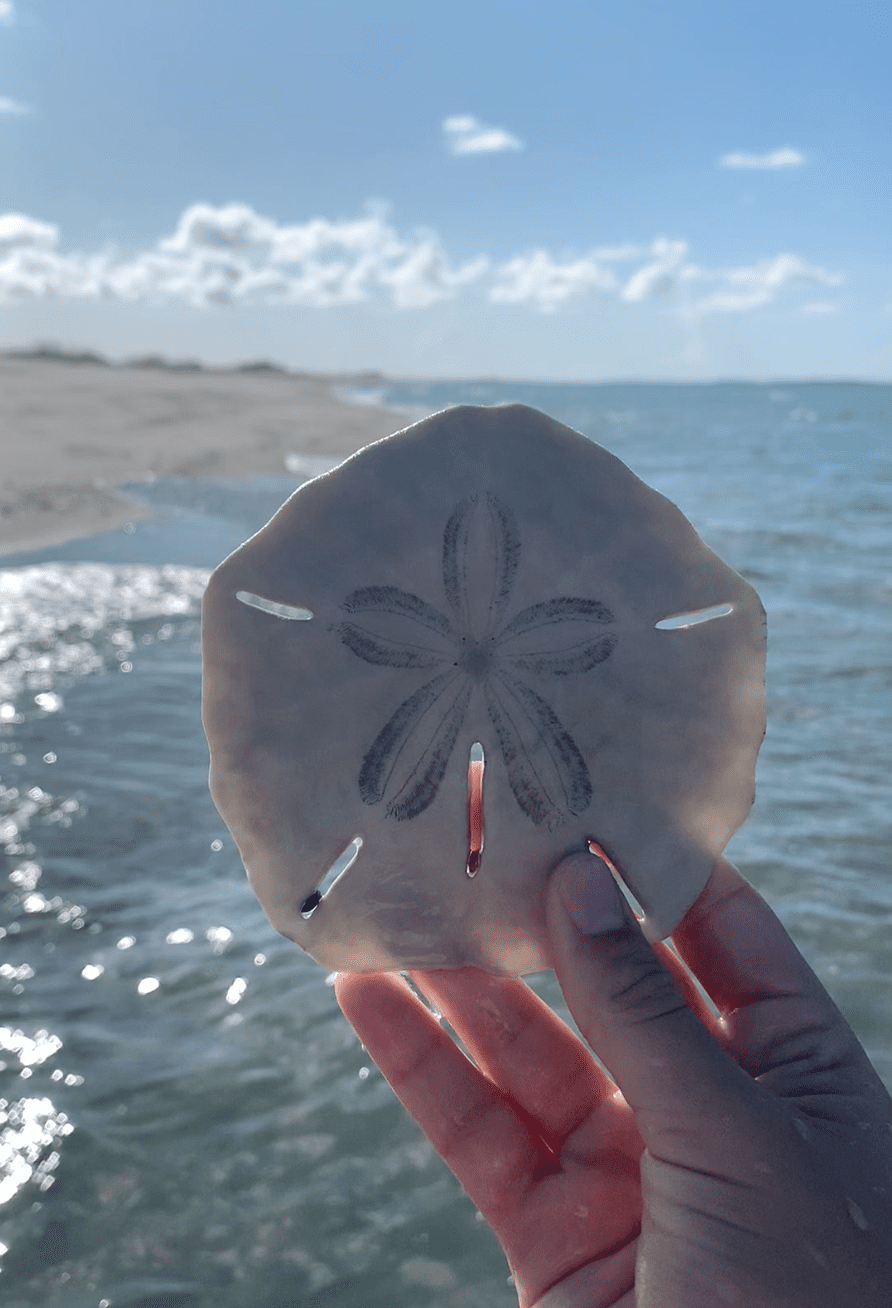

Never being one who can lie on the beach when there is so much to see and do, I set my stuff down, grab my shell bag, and set off along the shoreline. I’ve trained my eyes for a specific treasure when I am here. They are so abundant, and I trust I will find many since I am here at low tide. And just like that, seconds into my walk I see one. It is big, maybe five inches wide, but half of it is hidden in the sand. I bend down to dig underneath it a bit and pull up a fully intact, white sand dollar. First one of the morning!

The tricky part of shelling, or scouring the beach for the perfect shells, is that some of the shells have an owner, a tenant, or may just be alive itself. Honestly, it is frustrating sometimes. The shell that will forever elude me is North Carolina’s state shell, the scotch bonnet. Only once have I found a perfect scotch bonnet, and lo and behold, it housed a hermit crab.

As a marine science student, and an empathetic person with morals, I let the crab and with it that shell, go back to the water. There is often a large, heated debate among shellers about collecting sand dollars. Once, walking back along Gordon Street from a morning trip to Bird Shoal, I passed a neighbor sitting on her porch. She asked if I had any good finds and I held up my bag of sand dollars. In an accusatory tone she questioned, “You didn’t take any live ones now, did ya?” I said, “No, ma’am,” and held up a bleach-white suspect as proof. She didn’t look convinced.

Growing up as a so-called beach girl, spending much of my time on North Carolina’s coast, specifically around Topsail Beach and Beaufort, I sometimes take for granted my knowledge of marine life. I’ve always wanted to be a marine biologist; I just didn’t know that job really existed until a friend told me it was a real thing when I was 9 years old!

Learning about life on the estuaries so young, I sometimes forget that those unfamiliar in marine territories do not share my knowledge base. Appalled describes how I felt when, as a preteen, I was with a visitor who didn’t recognize a live sand dollar versus a dead one. It was an eye-opening experience to understand the importance of marine education.

Sand dollars and sea urchins are in the same phylum, the echinoderms. A similar feature in this phylum is their five-part symmetry, and tube feet, which I mentioned with the sea urchin. Tube feet help urchins move, but they are not extremely noticeable or visible compared to their long, obvious spines. In comparison, sand dollars have tiny spines and tube feet that cover their exoskeleton. When they are alive, they will be a dark color, like green or purple, and feel bristly to the touch. They use the spines and tube feet to move, eat and breathe.

If you find an intact sand dollar that is white and smooth to the touch, you have found a dead, dried-out sand dollar. What you see is its hard exoskeleton, or test, and there should be a flowery star-shaped pattern. Some people believe these creatures look like a flattened version of their cousin, the sea urchin. You can take a white sand dollar home with you, but be careful, because they are delicate and can easily crumble in your hand.

As I continue my walk east along Bird Shoal, I stay wading in the shallows looking for these small white disks that have gotten buried along the bank. “Ah!” I scream to no one as I scuttle out of the water to dry land. A small shark darted past me as I was reaching down for a shell. My affinity for sharks does not replace my respect for what nature could do to an uninvited guest to their home. I do not need to be swimming with sharks this early and while I am alone. I wait for the shark to swim away then continue my hunt. The sand dollars are abundant during low tide this morning! I add my treasures to the bag.

Occasionally I will look or walk up to the windblown dunes and see wild horses gathered in the marsh. During the beginning of the pandemic, another paradise-seeker had revamped one of the “Protect the Wild Horses” signs. It now states boldly “SHOAL OF SOCIAL DISTANCE.” I like that message, but the sign is fading now, as is our concept of social distancing. Maybe I will update it. Despite social distancing not being as prevalent now, Bird Shoal still offers and provides.

Pandemic or not, sometimes I need my own space.

On any one of my trips to Bird Shoal, I typically come back with around 20 to 30 sand dollars, five miles walked, two podcasts listened to, maybe a sunburn, and definitely dehydrated. However, another thirst is quenched. I am refreshed, feel accomplished and have been to my happy place. I can start the day stronger, ready to face whatever comes my way.

I am grateful to have discovered a peaceful place in the middle of a chaotic world, right out my back door. So close, and yet, at times, seems so far. Surrounded by the beauty of wind and water, seashells, sea creatures and sunshine. This place reaffirms my calling to environmental science and marine biology. The N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve work to preserve places just like this and keep them open to the public. These reserves are magical and can transport me even if I just close my eyes and imagine being there. I recommend visiting at sunrise. Listen for the splash heard as a pelican lands after gliding above. It almost sounds like a whale breaching.

This may sound cliché but a simple hike through Town Marsh and a walk along Bird Shoal puts me one with nature. Rachel Carson said it best, and I hold these words that get me through hard times: “Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.” How wondrous to know I find joy by exploring the same places, walking the same paths the inspiring and influential Rachel Carson did in the 1930s. In this volatile world, which seems to have more downs than ups these days, there is a place, my happy place, where it’s just me, my footprints, and my place on this planet.

To stimulate discussion and debate, Coastal Review welcomes differing viewpoints on topical coastal issues. See our guidelines for submitting guest columns. Opinions expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of Coastal Review or the North Carolina Coastal Federation.