A critical habitat for recreational and commercial species like spotted seatrout, red drum, bay scallops and blue crabs, North Carolina’s seagrasses improve water clarity and quality, and decrease shoreline erosion. However, scientists are finding that the essential habitat is declining because of deteriorating water quality.

To protect this economic and ecological resource, a private-public partnership is being formed under recommendation from the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan 2021 amendment, which focuses on improving water quality.

Supporter Spotlight

The Coastal Habitat Protection Plan, often called CHPP, was developed by state Department of Environmental Quality staff. First approved in 2004, the plan is updated every five years.

DEQ, The Pew Charitable Trusts and North Carolina Coastal Federation have been working this year to establish the partnership they’re calling North Carolina Stakeholder Engagement for Collaborative Coastal Habitats Initiative, or SECCHI, named after the Secchi disk, an instrument used to measure water quality.

With the main objective of SECCHI being to engage diverse groups of stakeholders to help develop, implement and secure decision-makers for funding for actions in the 2021 amendment, this core team organized and hosted a summit Oct. 19 to bring together these potential stakeholder and decision-makers to identify and organize around voluntary actions that protect and restore coastal water quality.

“The North Carolina Coastal Water Quality Summit: Stakeholders Driving Solutions” in New Bern gave a platform for local, county and state officials, scientists, community members and nonprofit organization leaders to share with attendees facts and experiences illustrating how declining water quality is affecting seagrasses.

“When you’re managing water quality, it requires a multifaceted approach that includes voluntary and regulatory measures, not just at the state level, but at the local and regional level. It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. And it is very complicated. But if we all work together on these different facets of it, we can achieve the common goal,” Division of Marine Fisheries Habitat and Enhancement Section Chief Jacob Boyd said that morning.

Supporter Spotlight

He explained that North Carolina’s estuarine waters provide floodwater storage and control carbon sequestration, which helps with greenhouse gasses, water quality treatment, erosion control, storm protection and support a higher biodiversity of different organisms that use them.

Water quality is the common denominator that drives the health of these ecosystems and the coastal habitats. Poor water quality is caused by the alteration of pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, bacteria, nutrient indicators, such as nitrogen phosphorus or chlorophyll A, excessive nutrient-rich sediment in the water, and nutrients in the system, which in turn decrease oxygen and water clarity.

“Climate change exacerbates these issues with rising sea levels, higher water temperatures, saltwater intrusion, and increased frequency and intensity of rain events adding more runoff,” he added.

Dr. Jud Kenworthy, a retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration research fisheries biologist, explained that submerged aquatic vegetation is probably one of the biggest challenges in terms of water quality because, unlike marsh vegetation or vegetation that partially grows in the air, submerged aquatic vegetation grows underwater.

“Anything that we do to affect the quality of water, especially the clarity of the water, is going to affect our submerged aquatic vegetation. And the most important factor of course is water clarity, because these are plants, they need light to grow. And without sufficient light they just can’t grow and can’t reproduce,” Kenworthy said.

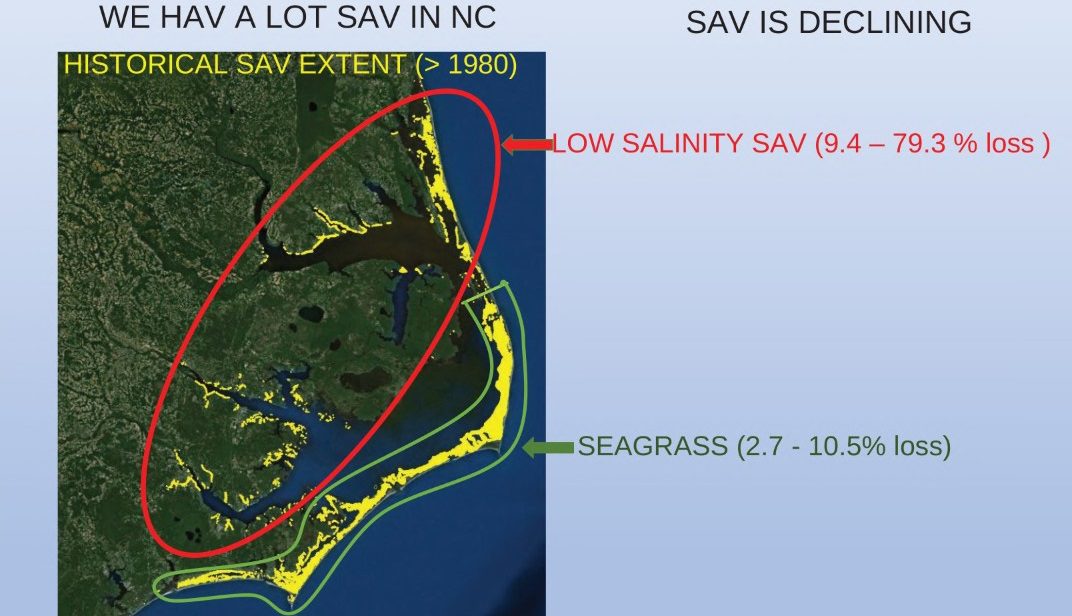

Seagrasses are declining. Based on surveys conducted in 2007 and 2013, the state has lost between 2.7 and 10.5% of seagrasses in high-salinity habitat, in the low-sanity habitat, about 9.4 to 79.3% loss. The cost of losing seagrasses in the next decade could be around $88 million. The cost to restore the resource is about three to five times higher than the actual value of the resource.

“The probability that you can actually restore it was about 36%,” he said.

University of North Carolina Wilmington Associate Professor Dr. Jessie Jarvis reiterated that clarity drives any kind of big change in seagrass. In the early 1990s, researchers determined that submerged aquatic vegetation are a good indicator of water quality because they don’t move, aren’t harvested and require light to grow. The only stressor can be directly linked back to environmental quality.

State Division of Water Resources Director Richard Rogers pointed out that the water quality challenges being faced are mostly human-made. Nonpoint source pollution is key, nutrients are the most widespread stressors impacting rivers and streams, about two-thirds of the nation’s coastal areas and more than a third of the nation’s estuaries are impaired by excessive nutrients, which contribute to algal blooms and can contaminate water used for recreation, drinking, wildlife, livestock, marine life and seagrasses.

Rogers said the Scientific Advisory Council is focusing on a draft clarity standard rule, also recommended in the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan, to present to the Environmental Management Commission. The council provides advice and recommendations to the division.

Adopting clarity standards at least sets the goal post for the level of water quality needed to have healthy and productive estuaries, Rogers added.

Importance of public engagement

Mike Blanton, a commercial fisherman and member of state Marine Fisheries Commission, said what he sees in the northern part of the state where he primarily fishes is that the waterways are extremely stressed daily, especially after significant rains.

“It’s vitally important that we start to understand these effects that it has on stakeholders like myself that are on ground zero that rely upon state resources, to ensure that there’s a coastal economy, to ensure that that we can carry on heritage and tradition of the state of what we’ve been doing for hundreds of years,” he said.

Beaufort Mayor Sharon Harker said when people come to the Carteret County town, they don’t think about water quality “but we have to also educate them that beauty can be at risk.” The town has developed a watershed restoration plan to help mitigate flooding but looking ahead, the town needs to continue partnering with stakeholders like those at the summit to find ways to protect its waterways.

Wilson Daughtry, a Hyde County farmer and operations manager for the Mattamuskeet Association, has been working with the Coastal Federation for more than 20 years.

“Stakeholders are necessary, a necessary group, and hopefully it’s a diverse group. Hopefully you’ve got landowners involved, state, local, federal people who have interest. That’s what it takes,” he said. but you have another subset, called the shareholders, or a person who has a vested interest in the project and is directly affected by the project. “Shareholders become your anchor point for your project. You need that shareholder to anchor that project to the local area.”

Department of Environmental Quality Secretary Elizabeth Biser commended the stakeholders during the summit.

“I don’t have to tell you all there are so many challenges facing our coastal waters. But I am so heartened to know what a strong commitment this stakeholder community has tackling these issues and making progress together,” she said. “We all know multiple sources that are contributing to contamination and degradation over time. That’s why the CHPP takes a holistic view to address these issues that are traditionally covered under different jurisdiction.”

Biser said she often talks about partnerships and the CHPP was a good example, explaining that every stakeholder has a different role to play while working toward the common goal.

“I appreciate all of you being here today, because by sharing your expertise, you’re helping us make better decisions as an agency,” Biser said, adding that the stakeholders are not just sharing their perspective but also bringing actionable solutions, and feedback to help DEQ make better decisions to manage state resources.

Habitat Program Supervisor for the Division of Marine Fisheries Anne Deaton said their goal through the public-private partnerships is to have additional minds at work “because people think differently, they have different expertise, different strategies. And so, we know we’ll get a better product if we work together.” Deaton is a member of the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan Steering Committee.

Next steps

Leda Cunningham, an officer with The Pew Charitable Trusts, explained after the summit that Pew’s involvement came out of its work on the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan amendment during 2021.

The Coastal Federation and Pew formed a small stakeholder group last year to make supplemental recommendations, including the stakeholder group suggestion, for the 2021 amendment. These were presented to the steering committee that added the public-private group to the amendment. The organizations teamed up earlier this year to develop the SECCHI strategic plan, which was approved by DEQ in June. One of the outcomes was to hold the summit to bring together stakeholders to work on regulatory voluntary measures.

Cunningham said there’s a lot of energy in water quality right now. The summit with leaders, scientists, farmers, lawyers was “meant to demonstrate, and did loud and clear, we all agree on the problem.”

On a parallel track, Pew has been working on the clarity standard rule, she added.

Eliza Wilczek, submerged aquatic vegetation campaign coordinator with the Coastal Federation, explained that the core team invited 13 different stakeholder groups that they knew had an interest in water quality. From those groups, the 111 attended contributed ideas and possible solutions.

“We’re not totally sure what the workgroup is going to look like at this point. That’s part of our post-summit action,” Wilczek said. “The next step is creating that workgroup and trying to keep the momentum of the summit going within the stakeholder groups.”

Deaton said after the summit that she was pleased with the turnout from a variety of backgrounds that share a common concern about coastal water quality.

“We want that energy to continue. The goal is to create a collaboration of stakeholders that can work together on a few specific strategies. While the state agencies are charged with managing water quality for a variety of public trust uses, they cannot do it alone. The public can bring innovative ideas, solutions and assistance to improve water quality through a variety of ways,” she said.

Next, attendees are to be provided with follow-up information to see who can commit to participating in the water quality stakeholder group, or SECCHI. Others interested but could not attend are welcome to contact the Coastal Federation or DEQ. “Their participation can really make a difference,” she added.

Boyd reiterated after the summit that water quality is not a single stakeholder, agency or organization issue, rather it’s one that touches many different facets on the coast, and it’s going to take a collaboration like this public-private partnership to be impactful.

The core team plans to use the feedback to mold the next steps, “but the biggest thing is to keep the momentum going, and, and for the core team to figure out the most effective and efficient way to do that,” he said.