WILMINGTON – No matter how incessant the public frustration or how desperate the pleas from mariners to fix clogged harbors, impassable channels or eroded shorelines, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is struggling to address worsening problems in coastal North Carolina, especially on the Outer Banks.

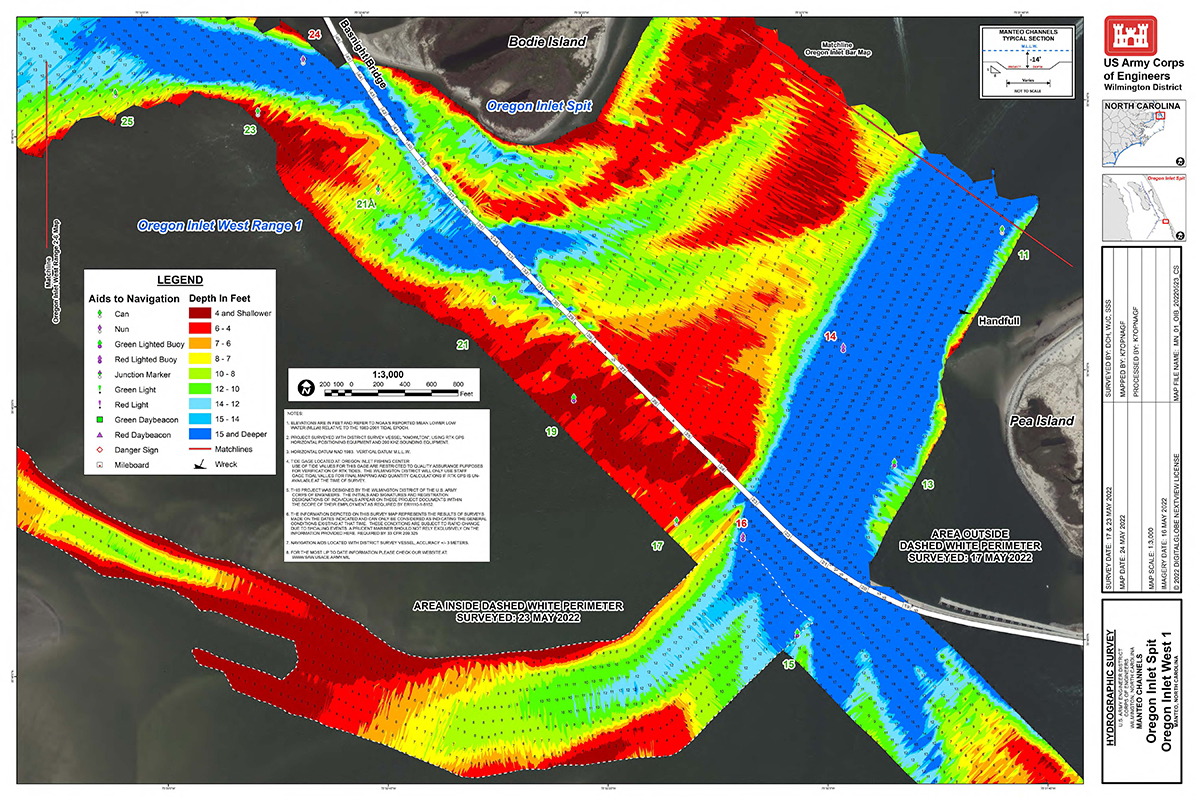

Recently, a wicked nor’easter wreaked havoc in Oregon Inlet, choking it with sand and making navigation too hazardous even for heavy-duty dredges. While such events in the dynamic waterway on the north end of Hatteras Island aren’t unusual, their impacts seem harder to fix. There is concern that as the climate is changing, the hazards and costs of channel maintenance will increase, potentially becoming unsustainable in places.

Supporter Spotlight

The Corps is not alone in coping with challenging maritime conditions from rising seas and intensified storms. Numerous private dredge companies as well as state and federal agencies, often the North Carolina Department of Transportation and the U.S. Coast Guard, partner with the Corps on projects.

A May 20 statement issued by the Corps’ Wilmington district blamed the storm, which pounded the coast for five days beginning May 8, for completely shoaling a portion of the federal marked channel along the Marc Basnight Bridge. With only 2 to 3 feet of water — barely enough draft for a skiff — the area was deemed impassable for most vessels.

Days before, the U.S. Coast Guard announced that it had marked a new channel in Hatteras Inlet, which is on the south end of the island, because the last marked channel had become irreversibly shoaled. Like Oregon Inlet, storms had made the previous passage so unnavigable that it was too dangerous to dredge.

The Coast Guard is also planning to remark the channel at Oregon Inlet, where local charter boat captains have found an alternate channel under the bridge to the ocean.

Such weather-created woes have become more frequent in the last decade or two, and it’s not just an issue on the 320-mile North Carolina coastline. Numerous waterways and shorelines where the Corps works, including along the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River basin and the Great Lakes region, also are experiencing more extreme conditions.

Supporter Spotlight

On the Outer Banks, with its jutting geography exquisitely exposed at the northern end of the Atlantic’s hurricane alley, there have been dramatic differences in sand travel in the last two decades, requiring more nourishment on its beaches and more sand removal from its waterways. The fact that conditions at times have become too poor for a dredge to tackle is an indicator of the dire shift in coastal patterns.

Prior to a series of severe storms starting with hurricanes Floyd and Dennis in 1999, Hatteras Inlet was stable and required little more than routine maintenance dredging for the ferry route. But since 1993, the passage from the Atlantic to Pamlico Sound between Hatteras and Ocracoke Island has widened from a quarter-mile to 2.3 miles, resulting in a precipitous increase in shoaling and dangerous exposure for vessels to wind and currents.

Still, with harbors, inlets, sounds, rivers and bays intersecting with the entire shoreline, North Carolina’s coast is exceptionally complex, environmentally and geologically. At the same time, it’s critical to the state’s maritime commerce, tourism and culture.

“So it’s a very dynamic system we have to keep our eye on,” Kathleen Riely, executive director of the nonprofit North Carolina Beach, Inlet and Waterway Association, or NCBIWA, said in a recent interview. “And dredging is a key part of that maintenance. It’s absolutely necessary.”

Nationwide problem

Riely said that shoaling and erosion are becoming more problematic not just along North Carolina’s coast, but also nationwide. As a result, demand for dredges everywhere has increased.

“I think with the dredges getting older that the Corps use, and having to go into repair shops is certainly an issue,” Riely said. “But there are a lot of private companies out there.”

Even in federal channels that the Corps is charged with maintaining, the agency is mandated by law to contract with private dredge companies when possible. The Corps can also work in nonfederal channels under formalized agreements. For instance, the agency is paid by Dare County and state funds under a memorandum of agreement to do work in Hatteras Inlet.

Numerous dredging projects nationwide were recently funded by the $1 trillion infrastructure legislation passed last year, which provided $17 billion to the Corps for work in harbors, ports and inland waterways, said Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., chair of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure during a congressional hearing in February.

“As we authorize new projects, the other side of that coin, as always, is ensuring that the Corps has the funding necessary to complete the work,” DeFazio said, according to minutes. “We all know of the $100 billion backlog of projects due to underfunding of the Corps for decades.”

Even with the flood of newly funded projects throughout the country, there will still be enough interest from the private sector in North Carolina projects, according to an email from the Corps’ Wilmington district in response to an inquiry from Coastal Review.

But beyond what the private dredges can do, the Corps’ small and aging dredge fleet that works in the district is stretched thin.

“As you are aware, our fleet works on coastal projects from Maine to Texas, and at times, demand does exceed the capacity of our shallow-draft fleet,” Wilmington District Corps spokesman Dave Connolly wrote in the email.

“The coastal environment has been and continues to be dynamic,” he said. “Subject to appropriations and funding, the Corps will continue to use industry (private company) and government dredge resources to maximize maintenance of waterways, embracing beneficial use of material when practical.”

The Wilmington District has made major investments in the shallow-draft fleet over the past decade, he added, including replacement of the Dredge Fry with the Dredge Murden in 2012, and completing a major shipyard overhaul for the Dredge Merritt in 2018. Currently the Dredge Currituck is in the shipyard undergoing major restoration that will be completed in 2023.

The 78-year-old Merritt, a side-cast dredge, mostly works in North Carolina, but it occasionally lumbers over to the Charleston, Norfolk and Philadelphia districts. The split-hull, shallow-draft, or hopper, Dredge Currituck, a comparatively youthful 48 years old, toils throughout the Atlantic and Gulf regions. And the hopper Murden, a young workhorse at age 10, also covers the Atlantic and Gulf.

“Within the District the shallow draft fleet is used on about 10 federal waterways routinely, from Lockwood Folly Inlet to Oregon Inlet,” the email said. “Nationally, the fleet is used on approximately 50 projects, although all are not dredged every year.”

With dredging restricted during the spring and summer months along the North Carolina coast when protected sea turtles breed, it can be complicated scheduling dredging windows to match needs.

As the federal government’s primary agency in charge of civil works project with roots going back to George Washington, much of the maritime-related funding over the years has been focused on large harbors and ports, leaving shallow-draft projects competing for small pools of money. For that reason, hopper dredges that are typically used to maintain harbors are an important focus for Corps’ dredging operations. Use of hoppers, large vessels that can hold a lot of dredged material in their holds to be dumped offshore, has been subject to various constraints, with mixed results, as shown in a U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report from 2014.

“The restrictions, however, help ensure the Corps has the ability to use these dredges to respond to urgent or emergency dredging needs when industry dredges are unavailable,” the report said. “It is not clear to what extent restrictions have affected competition in the dredging industry.”

Although private industry hopper dredges are allowed to respond to urgent dredging needs, the report said, it added that it did not track how often that was done.

According to federal law, the Corps is directed to contract with private dredge companies whenever possible rather than using Corps dredges. For that reason, the Corps does not plan to build or purchase new shallow-draft dredges, said Corps spokesman Connolly.

A new dredge, he said, would cost roughly $25 to $30 million to build, although inflation could make any estimate a moving target.

“With the recent investment in the Dredge Merritt and Dredge Currituck, we are expecting several more years of useful service, and in consultation with our higher HQ (headquarters), will evaluate and analyze long-term options for replacement or future rehabilitation of these assets.”

An Aug. 2020 issue brief published by the nonprofit National Taxpayers Union Foundation found that the U.S. is lagging behind Europe and China in modernizing its equipment, resulting more expense and labor to remove less material.

“The longer dredging is not updated or improved with technology, the greater costs will be over time,” the paper said. “Despite the general trend of higher annual spending on dredging, by some measurements efficiency and productivity have lagged expenditures.”

The ongoing supply chain problems related to international shipping has brought more awareness to the value of waterways in commerce, but small harbors are still under appreciated for their value to local communities for tourism, fishing and recreation.

“There remains relatively little political action around the issue of dredging as it doesn’t occupy the top of Congress’s list of priorities,” the Taxpayers Union report said. “But those immediately impacted by the continued accumulation of sediment within American waterways have long been petitioning their representatives as well as the Army Corps of Engineers for relief.”

Miss Katie

Meanwhile, Dare County’s new hopper dredge, the Miss Katie, is expected to be delivered to Oregon Inlet in July and operating by August, said Barton Grover, administrator for Dare County Waterways Commission. He added that the dredge is just like the Murden, except it also has side-cast capabilities.

Construction of the 156-foot dredge, a public-private partnership, was paid for by a state allocation of $15 million from the Shallow Draft Navigation Channel Dredging and Aquatic Weed Fund. The dredge’s work schedule, which has yet to be determined, will be managed by the Oregon Inlet Task Force.

Riely, with NCBIWA, said that it is an interesting and creative idea that could make counties less dependent on the Corps. But she said there still are questions: How much will it cost to maintain? Where are the funds going to continue to come from? Where will it be housed when it’s not operating?

“So there’s some issues with it,” Riely said. “But I think if it can work out, having a dredge in North Carolina just for our coasts, let’s say there’s one southern going halfway or whatever, the other north coming down, I think that would be a good thing.”

Next in the series: Worsening shoaling and erosion, and other effects of climate change on coastal conditions, have been creating more difficult challenges for both dredges and ferries on the Outer Banks. That is especially a concern on Ocracoke Island, accessible only by boat or airplane, where hundreds of year-round residents and millions of annual tourists depend on the ferries for their transportation to and from the island.