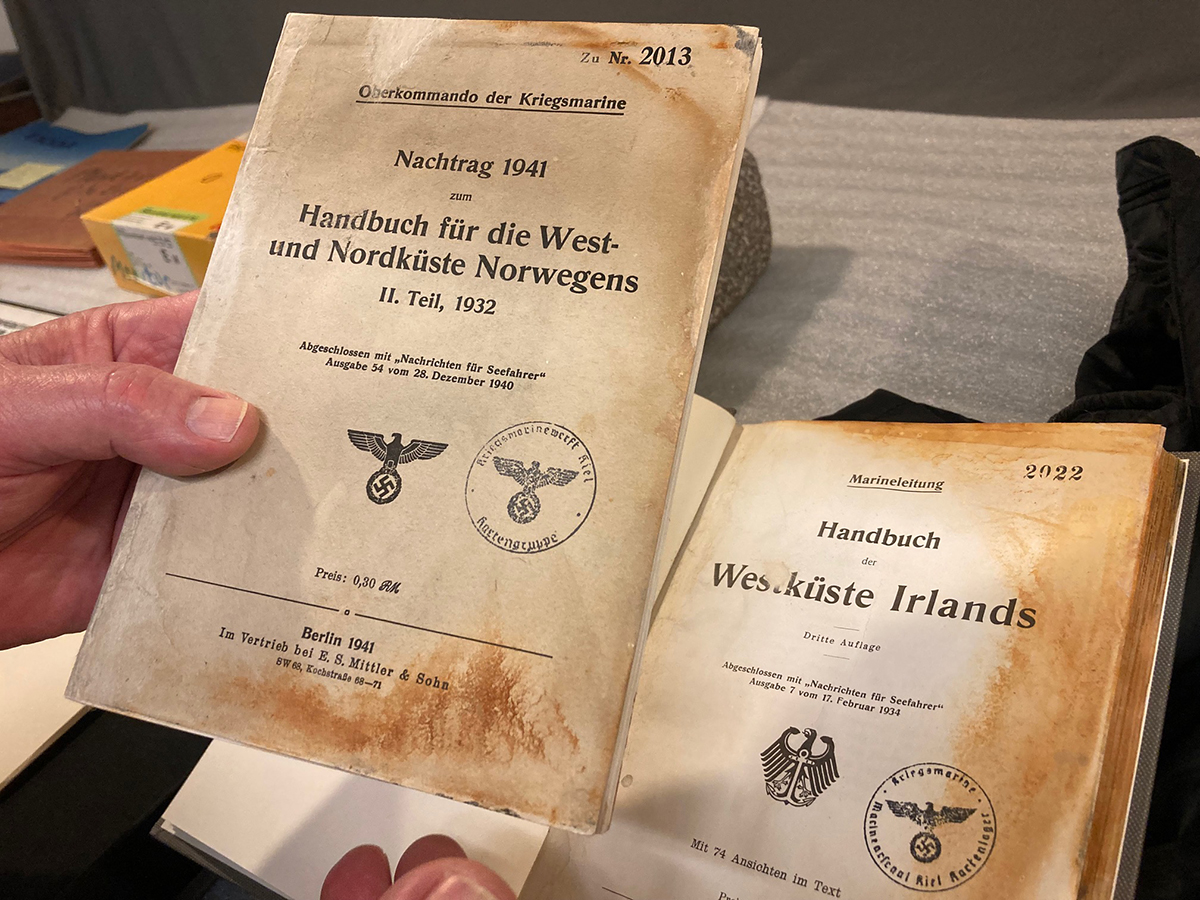

HATTERAS — One day about two years ago, a shoebox wrapped in plastic arrived at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum. Inside, there was a manual, written in German and stained orange by diesel fuel. Chillingly, it included maps of the North Carolina coast, marked with the locations of lighthouses.

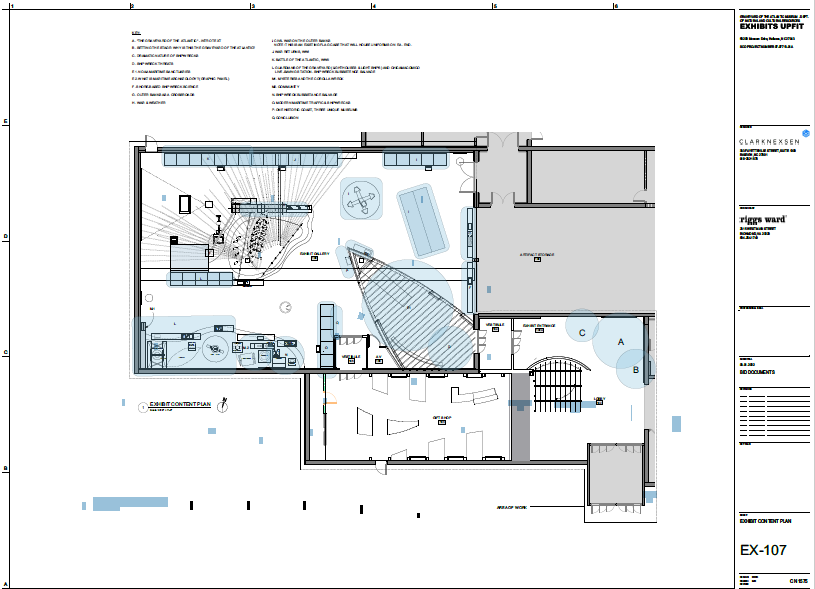

With $4.2 million provided in this year’s state budget to fabricate and install the Hatteras museum’s exhibits, the public may soon be able to see the relic of the gruesome Battle of Atlantic, along with hundreds of other never-seen historic maritime artifacts. Bids for the exhibit plan are expected to go out soon.

Supporter Spotlight

“I am so pleased that this is done for Hatteras and North Carolina,” said North Carolina Maritime Museums Director Joseph Schwarzer, referring to completing the museum that was inspired decades ago to preserve the Outer Banks’ maritime history, “because this is important. Once you lose it, you never get it back.”

Standing earlier this year in the climate-controlled area behind the museum’s gallery, Schwarzer explained that the package of artifacts came from an unnamed diver who had retrieved the documents from the wardroom of the U-85, a German submarine torpedoed off Nags Head in April 1942 — the first U-boat the U.S. Navy had sunk during World War II.

“They had all these books on the shelf,” the director said recently while showing off the manual the diver sent. “Fortunately, he put it in the freezer.”

‘Good stories, and there’s a lot of them’

Schwarzer was surrounded by remnants of many more astounding artifacts to soon be relocated from storage to exhibit space, ranging from detritus to whole pieces and memorializing centuries of dramatic maritime history off the Outer Banks that encompasses piracy, colonization, wars and thousands of shipwrecks, as well as history shown through its people — the U.S. Life-Saving Service rescuers, lighthouses and lifesaving stations, commercial and recreational fishing, diving and salvaging, and nor’easters and hurricanes.

“The point is, there’s nothing here that isn’t historically significant,” Schwarzer said. “That comes back to, ’Let us tell our story.’ They’re good stories, and there’s a lot of them.”

Supporter Spotlight

As an example, he pointed to the stored equipment that had been used by the U.S. Coast Guard to conduct the last rescue with a breeches buoy, a type of seat developed by the lifesaving service to carry shipwreck victims to shore. That artifact, along with the Lyle gun that shot the line used to carry it, was interesting to see, but the saga afterwards made it much more so.

In the story Schwarzer summed up, the Honduran freighter Omar Babun was transiting off the coast near Rodanthe, heading to Havanna, Cuba, loaded with heavy equipment for a steel mill. The ship was caught in a gale and beached May 14, 1954. The Coast Guard rescued all 14 crew members with the breeches buoy.

The juicier part happened after the ship grounded. According to a Time magazine story that ran Aug. 2, 1954, a Buick dealer from Havelock and named Esveld “Nip” Canipe, had after flying over the ship in a chartered plane, decided to salvage the 194-foot Omar Babun, with an agreement with the insurance company that he would get 30 % of the value of the cargo he recovered.

Miraculously, Canipe and a team of about 30 men, including 25 skeptical Outer Bankers, built a road to the ship and managed — just barely and with much effort — to pull cargo ashore. Canipe later refloated the Babun and got it to port in Norfolk. He was expecting to make about $100,000 in profit, over the estimated $40,000 cost of the salvage operation, the article said.

Meanwhile, Babun’s captain, who “may or may not have been working for the CIA,” Schwarzer said, later had one of his boats intercepted by the Cuban government, which might have been unhappy about the undelivered cargo. Another interesting tidbit is that Cuban leader Raul Castro is said to have been living in the captain’s old house in Cuba.

“This is a nothing shipwreck, but when you delve into it, it’s got all these aspects,” Schwarzer said.

And that what’s got Schwarzer so excited about finally being able to complete the exhibit work at the museum — the long-hidden-away artifacts can now tell the stories.

A long-incomplete but popular attraction

The genesis of the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum goes back to 1986, when Hatteras villagers decided it would make sense to have a facility to house artifacts from the wreck of the Civil War-era Monitor that had been discovered a decade earlier offshore their village. Most of the items salvaged from the ironclad ended up going to the Mariner’s Museum in Newport, Virginia, but considering that about 2,000 or more ships were believed to have wrecked off the North Carolina coast, mostly along the Outer Banks, the concept of a shipwreck museum nonetheless gained momentum.

In 1999, ground was broken on the proposed $7 million facility, situated on a 7-acre site owned by the National Park Service at the south end of Hatteras Island. Initial costs were provided by project partners, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the park service.

The museum opened to the public in 2003 with changing exhibits, albeit incomplete exhibit space. The 19,000-square-foot museum has proven to be a popular attraction. It was transferred to the state in 2007, joining the system’s maritime museums in Beaufort and Southport. Although NOAA had earlier provided $600,000 for an exhibit design, estimated costs for the exhibit design started at about $2.5 million and kept inching up over the years and it remained unfunded.

The exhibit plan, estimated at $4.2 million, was approved last year.

Named in honor of the nickname given to Diamond Shoals, the treacherous area off Hatteras Island where for centuries many hundreds of ships wrecked, the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum is dedicated to preservation of not just shipwrecks, but to the 400 years of maritime history and culture of the Outer Banks.

The museum, which is free to visit and located across from Hatteras-Ocracoke ferry docks at the end of Hatteras Island, has featured new themed exhibits on a seasonal basis and offers year-round programs, including popular family-friendly scavenger hunts.

Despite being incomplete, the museum already has numerous detailed exhibits in its expansive gallery, themed on fishing, diving, the Civil War, World War I, World War II, piracy, lifesaving, Native Americans and storms. Artifacts on display include Civil War battle flags and garments, the bell from the Diamond Shoals lightship, an Enigma decoding machine salvaged from a U-boat, the original telegram sent from the Titanic that was discovered in the wall of the nearby weather station, and the partially restored original Fresnel lens from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

There is also a large window in one part of the gallery where visitors can look at the artifact collection, which Schwarzer estimated totals more than 100,000 objects, in storage, with selected highlights rotated in front of the window.

In addition to the state appropriation, the museum depends on the $50,000 to $60,000 a year in donations that the public gives at the door, as well as funds raised by the museum’s nonprofit friends group, for programming and maintenance needs.

Once the installation is done, the hope is that members of the community, many of whom have lived on the island for generations, and whose family roots go back centuries, will donate treasured items, said Danny Couch, president of the museum’s friends group.

“We know that they’re there,” Couch said, adding that the issue is providing the assurance that the artifacts will find a suitable home. “We know that we can do that.”

In the past, Couch said, there were instances where community members had entrusted their family’s souvenirs after promises were made, but the objects were never seen again.

“That’s going to continue to be a sell to the local community, to make sure the comfort level is there,” he said.

Couch said he’s just glad that after years of struggle to finish the museum, they can now breathe easier and concentrate on programming rather than fundraising.

“It’s such a sense of relief,” he said. “After sailing around the world and coming into port, now we’re finally at the dock.”