During the past 1,000 years, migratory fish have played an important role in the survival and economic benefit of indigenous people along the Atlantic Coast, as well as early settlers to the New World.

Today, migratory fish including Atlantic sturgeon, American shad, alewife and blueback herring, and striped bass play a significant role in the recreational and commercial fisheries that contribute to the economy of North Carolina. And while these fish are important in employing thousands of workers, including those who catch and process them and manufacturers of lures, boats and other equipment, many have forgotten about the earliest fishers who sought the bountiful runs of silvery fish that migrated through the North Carolina coast and the entire East Coast.

Supporter Spotlight

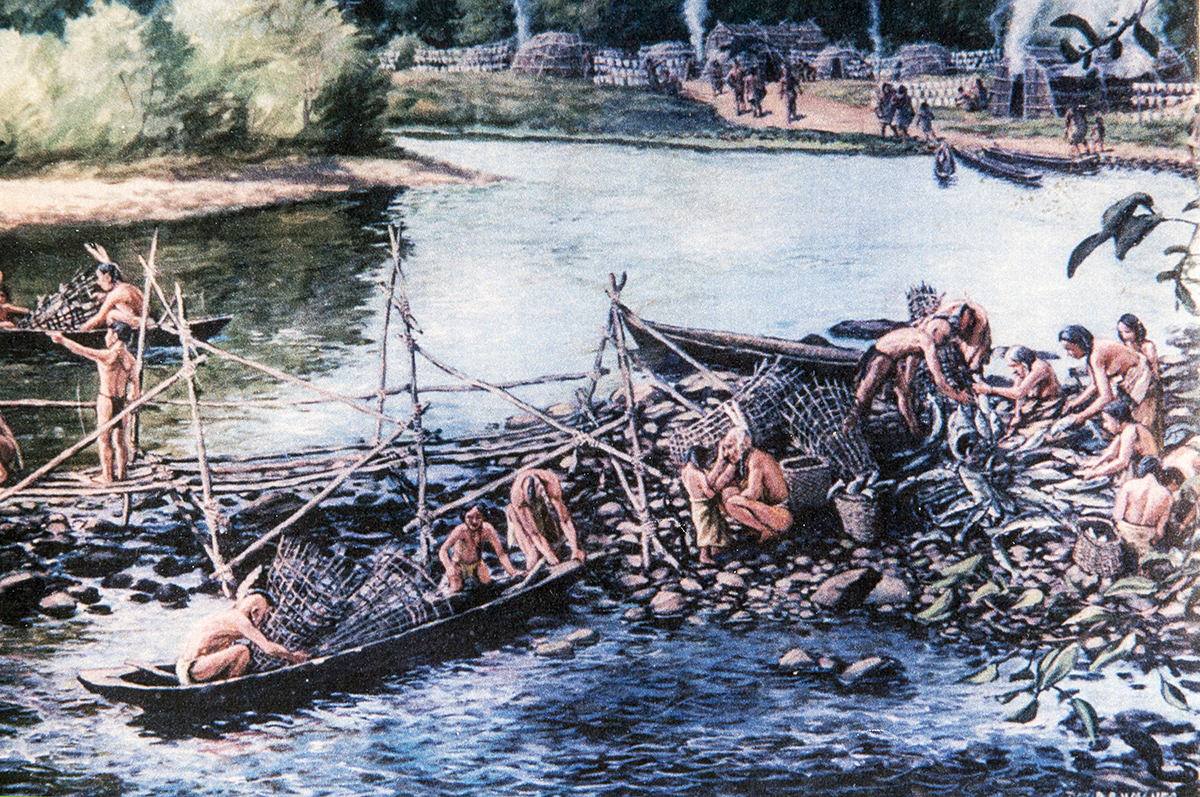

Before contact with Europeans hundreds of years ago, “Various methods were used by Indigenous people to catch migratory fish,” said David Weeden, director of the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe in Massachusetts.

“We would fish for sturgeon at night from our dugout canoes, utilizing a torch at the bow to attract these enormous fish. Then we would spear them, often time repeatedly because their scales are like armor. Often the spears would be similar to a harpoon. The fish would eventually tire out and be dragged to shore. Fishing for herring, including shad and river herring was done with weirs, throw nets and basket nets, sometimes on a cantilevered system fishing from the banks,” he said.

Using handmade tools and natural materials found along coastal waters, Indigenous people had no digital depth finders or graphite rods.

“The (migratory species’) numbers have significantly declined to where there are imposed bans for non-natives; aboriginal rights are recognized and we take only what we need. The fish were so plentiful historically that you could walk crossed the river on the backs of the herring and alewife. This was a staple source of income in the 17th and 18th centuries, where the herring were exported overseas to be canned,” Weeden said.

“Aboriginal hunting and fishing rights have been long established here in Mashpee, Massachusetts, though they are continuously challenged even today. Our access to historic fishing areas is constantly being impeded upon due to over development in coastal areas of our ancestral homelands. We continue to defend our aboriginal rights by exercising them when we go fishing, often being harassed by uninformed environmental officers; where the courts acknowledge and reaffirm our ancestral rights to hunt and fish,” he said.

Supporter Spotlight

Colonial America

With Europeans arriving on this continent in ever increasing numbers, the face of fishing changed forever. New technologies were invented, and other uses were created for profiting from the migratory fish in North Carolina and elsewhere along the Atlantic Coast. By the time the Revolutionary War had begun in the latter half of the 18th century, George Washington’s Mount Vernon Plantation was earning more money from its commercial fishing activities than from farming while Washington was away fighting for independence.

“Shad and river herring were very important to Mount Vernon Plantation for many reasons,” said Ann Rauscher, Mount Vernon Ladies Association. First of all, she said, it was a very important source of income. In many years, more income was derived from his fisheries than from his farming sales up and down the East Coast. “It was very important to Washington to have this dependable source of income. In addition, the shad and herring were used to feed his staff, family, and the slaves he had on the plantation.”

American shad was an important resource in Colonial America for a number of reasons, including as a source of food.

“The early Colonists used it for feed and as a matter of barter to exchange in the marketplace,” said David Whitehurst, retired director of the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. “The early writings speak of the fish being in such abundance that they would actually be bumping into boats as they tried to ply across the rivers to the point that we have in the record, that George Washington in one day of haul seining on the Potomac near Mount Vernon caught a half million dollars’ worth of fish in one day of haul seining.”

19th and early 20th centuries

“During the 19th and early 20th centuries, shad and sturgeon suffered from overfishing. There was a mechanization of haul seines, along with the introduction and proliferation of pound nets. A 1925 scientific study proved that pound nets were problematic. Gillnets were also an issue, as well as expanded transportation networks that fostered an expansion of the shad and herring fisheries,” said David M. Bennett, curator of maritime history with the North Carolina Maritime Museum System.

“North Carolina responded to overfishing by working with the U.S. Fish Commission on shad culture and enacted laws that placed limits on commercial fishing. With sturgeon, it went from being a trash fish to an extremely valuable fish in the 1880s. By the early 1900s, fishermen were struggling to catch sturgeon because they had been overfished. In the late 19th century, there was high demand and good profit margins for shad and sturgeon. That attracted a lot of fishermen to those fisheries and consequently they were overfished,” Bennett said.

The historical record mentions agricultural runoff and erosion, sewage from towns and industrial effluents as having a negative impact on shad and herring. Dams that served gristmills and sawmills were also cited as being problematic.

“Studies on the historical abundance of shad in the Albemarle, do indicate a general downward trend in shad during the 19th century with a peak in 1897 followed by a plummet in abundance going into the early 20th century. It was largely caused by overfishing,” Bennett said.

The Last 80 Years

In the early 1940s, recognizing that they could accomplish far more through cooperation rather than individual effort, the Atlantic coast states came together to form the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, or ASMFC. An interstate compact ratified by the states and approved by Congress in 1942 acknowledged the necessity of the states joining forces to manage their shared migratory fishery resources and affirmed the states’ commitment to cooperative stewardship in promoting and protecting Atlantic coastal fishery resources.

“The goal of the ASMFC is to promote the better utilization of the fisheries, marine, shell and anadromous, of the Atlantic seaboard by the development of a joint program for the promotion and protection of such fisheries, and by the prevention of physical waste of the fisheries from any cause. sustainable and Cooperative Management of Atlantic Coastal Fisheries,” said North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries Special Assistant for Councils Chris Batsavage.

Since the 1940s, the commission has served as a deliberative body of the Atlantic coastal states, coordinating the conservation and management of 27 nearshore fish species, including Atlantic sturgeon, striped bass, river herring, American shad and hickory shad.

Each state is represented on the commission by three commissioners: the director of the state’s marine fisheries management agency, a state legislator and an individual appointed by each state’s governor to represent stakeholder interests. These commissioners participate in deliberations in the commission’s main policy arenas: interstate fisheries management, fisheries science, habitat conservation and law enforcement.

“Through these activities, the states collectively ensure the sound conservation and cooperative management of their shared coastal fishery resources and the resulting benefits to the fishing and nonfishing public,” Batsavage said.

Two pieces of legislation, the Atlantic Striped Bass Conservation Act in 1984 and the Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Cooperative Management Act in 1993, were seen as the kind of success that can be achieved when state and federal agencies and Congress join forces to rebuild coastal fisheries.

“ASMFC management was voluntary before these acts. The acts require all Atlantic Coast states that are included in an ASMFC fishery management plan to implement required conservation provisions of the plan or the U.S. secretary of Commerce, and the secretary of Interior in the case of striped bass, may impose a moratorium for fishing in the noncompliant state’s waters, which improved the effectiveness of ASMFC management,” he said.

Due primarily to overfishing during the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s, as well as pollution and habitat loss, the fate of many migratory fish was set. The Atlantic sturgeon and shortnose sturgeon are now listed as endangered on the Endangered Species List, while both species of river herring and the American shad are shown as species of special concern.

The striped bass fishery is considered the only success story among migratory species covered in this report, but unfortunately its stock is again overfished. Coastal migratory stocks of striped bass are managed under a fishery management plan developed by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission under the authority of the Atlantic Striped Bass Conservation Act. Stringent management measures, including harvest moratoria, were implemented by states from North Carolina to Maine to rebuild the depleted coastal stocks with particular focus on the Chesapeake Bay stocks.

“Reduced harvest along with strong year classes from Chesapeake Bay entering the population helped the population grow,” ” Batsavage explained.

In 1995, Atlantic striped bass were formally declared to be restored and commercial and recreational management regulations were relaxed. Current management measures include size limits, seasonal closures, recreational daily bag limits and annual commercial catch quotas, he continued.

“Fisheries remain limited to state waters due to the continued moratorium on fishing for striped bass within the Exclusive Economic Zone. ASMFC’s Striped Bass Management Board is currently developing an amendment to the fishery management plan to end overfishing and rebuild the spawning stock,” Batsavage added.

In addition to interjurisdictional management through ASMFC, the Atlantic Coast states conduct biological monitoring and implement management of these species. While some of the management and monitoring efforts are ASMFC compliance measures, other efforts are for state-specific objectives.

“For example, the striped bass stocks in estuarine waters south of Albemarle Sound are managed by the state of North Carolina because these stocks are not part of the coastal migratory population of striped bass managed by ASMFC,” Batsavage said.

To learn more about the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s history, visit http://www.asmfc.org/files/pub/FKIC_Ebook/index.html.