Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

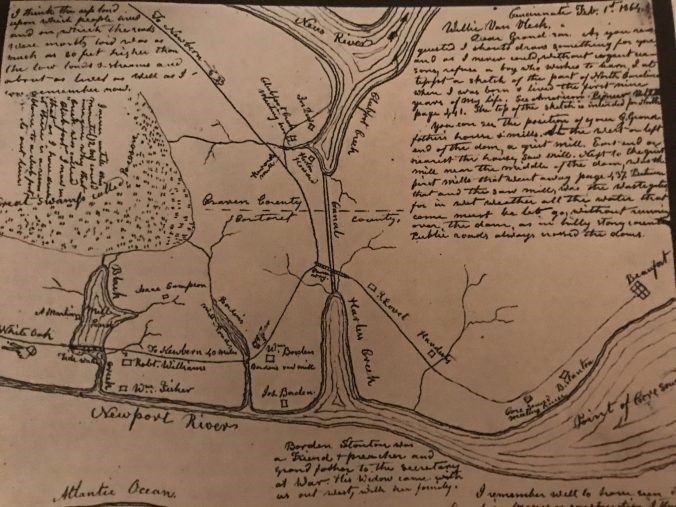

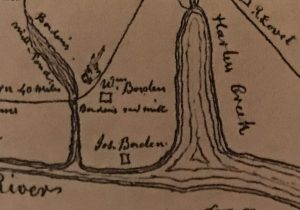

I recently found this map in an old book called “The Williams History: Tracing the Descendants in America of Robert Williams, of Ruthin, North Wales, who Settled in Carteret County, North Carolina, in 1763.” The map describes a largely forgotten group of Quaker settlements that flourished on the North Carolina coast more than 200 years ago.

Supporter Spotlight

I have strong family roots in that area, so I was aware that Quakers had been among the region’s earliest colonists. But I had never seen anything like this map. For the first time, I could really see the large extent of Quaker settlement in the 1700s in the area on the north side of the Newport River.

That includes the communities that we now call Harlowe, Mill Creek, Black Creek, Core Creek and Ware Creek.

All are located a little west of Beaufort, North Carolina. Most are in Carteret County, though some are just across the county line in Craven County.

A Quaker named John Shoebridge Williams drew the map. He was born at Black Creek, on the lower left of the map, in 1790. He did not make the map until 1864, however, long after he had left the area and moved to Ohio.

He drew the map because he wanted to show his children and grandchildren where he had lived as a child.

Supporter Spotlight

Compiled by Milton Franklin Williams, one of his descendants, “The Williams History” was published in 1921.

“The Williams History” included John Shoebridge Williams’ map, as well as some of his letters and reminiscences about the Quaker communities in that part of Carteret and Craven counties.

Today I’m going to look closely at this map to see what it can tell us about those Quakers.

With the help of the documents in “The Williams History,” as well as some others, I’m going to explore the history of those Quakers and of the Africans and African Americans who were at one time enslaved by them and, in many cases, freed by them.

The Clubfoot Creek and Harlowe Creek Canal

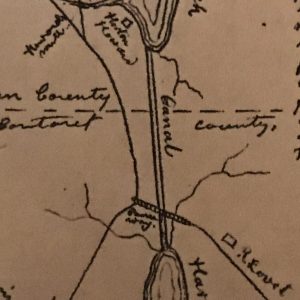

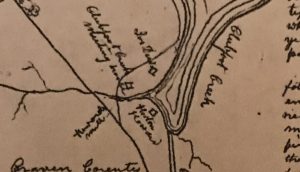

Perhaps the most central landmark on the map is the Clubfoot Creek and Harlowe Creek Canal. You can see it running in a north-south direction in the very middle of the map.

It might help you to judge the map’s scale if you keep in mind that the canal is 3.4 miles in length.

The map portrays the region ca. 1799-1800. At that time, enslaved African and African American laborers had just finished digging the canal, which was one of the first ship canals in the American South.

That was before the invention of hydraulic dredges, so the enslaved workers cleared and excavated the route with shovels, axes and mattocks. They dug, but also cut through a thick mat of roots. Often they worked in waist-deep water.

When completed in the late 1790s, the canal provided a passage for shallow draft vessels to travel from the Neuse River to the Newport River, and hence to Old Topsail Inlet and the sea.

The canal was not much more than a broad ditch at that point in time, however. Other enslaved workers would enlarge and deepen the canal further in the 1820s.

To the north of the canal, the map shows two bodies of water, Clubfoot Creek and the Neuse River (Williams spells it “Neus”).

To the south of the canal, the map shows Harlowe Creek, the Newport River and the Atlantic Ocean (really Bogue Sound). All are estuarine waters at that point.

Meetinghouses, Mills and Millponds

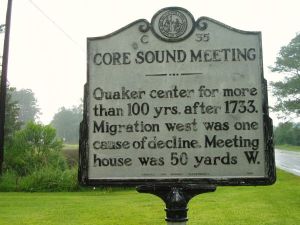

Two other important landmarks are the Quaker meetinghouses. The first is the Core Sound Monthly Meeting, which you can find on the right-hand side of the map.

It is located on the road that runs along the north side of the Newport River toward the little seaport of Beaufort.

The other is the Clubfoot Creek Monthly Meeting. You can see it on the central, upper portion of the map. The meetinghouse stood near Clubfoot Creek, a tidal bay on the south shore of the Neuse River. The meetinghouse was just across the county line in Craven County.

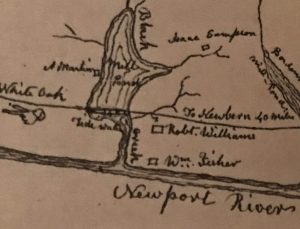

Another important feature on the map are the mills and millponds. On the lower left side of the map, John Shoebridge Williams indicated the sites of two millponds and three mills on the north shore of the Newport River.

In the 1790s, those mills were a central part of the local economy. On the far left of the map, you can see the first millpond, which was formed by the damming of Black Creek, a tributary of the Newport River.

That millpond still exists. It is known today as Walkers Millpond, and you can see it from State Road 1154 (the Mill Creek Road).

The map shows a gristmill on the east end of the milldam and a sawmill on the west end.

Robert Williams, the mapmaker’s father, established both of those mills. After his death in 1790, his neighbor, William Fisher, operated at least one of them.

On the map, you can see Fisher’s plantation just east of Black Creek.

Timber, Naval Stores and Salt Works

Robert Williams was one of the central figures in the local Quaker community. A Welsh immigrant, he had settled in Carteret County in the 1760s, lured to the region by its extensive old-growth forests and the prospects of making a living from the lumber and naval stores trades.

The map shows the site of the Williams family’s plantation just east of the millpond on Black Creek.’

According to family papers and other local records, Robert Williams’ plantation included the two mills, roughly 1,200 acres of land, at least one seagoing vessel and several hundred enslaved laborers.

In addition, he owned a salt works in Beaufort, 9 miles to the east, and general mercantile stores in Beaufort and New Bern.

The port of New Bern was situated on the Neuse River, roughly 40 miles to the northwest, and was the seat of Craven County. The Williams plantation was located on a road that led to New Bern.

The Rhode Island Connection

If you follow the Newport River downstream, you’ll find another millpond on the map. It’s roughly 3 miles east of Black Creek and was known as Borden’s Millpond.

One of the region’s earliest colonists, a Quaker named William Borden (1689-1749), had formed the millpond by damming what became known as Borden’s Creek.

That millpond no longer exists. Today the creek is known simply as “Mill Creek,” as is the modern-day community there.

William Borden, Sr., and his family moved to the area from Newport, Rhode Island, in 1732. They were hardly unusual, a large part of the Friends that settled in this area also came from Rhode Island.

That is how the local river came to be called the Newport River, and how the nearest modern-day town, Newport, got its name as well. Today the town of Newport is located 3.5 miles west of Black Creek, which places it beyond this map’s left border.

William Borden, Sr., hosted the first Friends meeting in Carteret County at his home in 1733. On the lower, central part of the map, you can find the site of that meeting between Borden’s Creek and Harlowe Creek.

When he arrived from Rhode Island, William Borden, Sr., established a shipyard and plantation there at the juncture of the Newport River and Harlowe Creek. In time, he became the county’s largest landholder.

His properties extended from Bogue Banks, a barrier island south of Beaufort, to the modern-day community of Harlowe.

(By the way, I’m using the modern spelling of “Harlowe” with an “e” at the end. In the 1700s, the name often appeared without that “e,” like it does on this map.)

According to a Borden family history that was published in 1899, William Borden, Sr., imported shipwrights and timber crews from Rhode Island to work on his lands.

Most were seasonal workers. At the end of every winter, they returned to Rhode Island in order to avoid the summer heat and the malaria season.

As did most of the landholding Quakers in this area, William Borden, Sr., also employed enslaved African and African American workers, at least in the early and mid-1700s.

The “Great Swamp called Pocoson”

The map shows a fourth mill approximately 8 miles north of the other three mills. It is labeled “Howards Mill.” You can find it near the Clubfoot Creek Meeting House in the upper, central part of the map.

As you can see on the map, Horton Howard, a Friend and the mill’s owner, resided just to the east of the mill.

In addition to owning the mill, Howard was a surveyor and a self-educated physician whose interest in medicine was apparently spurred by his own chronic illnesses as a boy and a young man.

Many years later, he became known for writing a 3-volume series on the herbal treatment of diseases. He published the first volume,”An Improved System of Botanic Medicine,” in 1832.

The map does not indicate a millpond at the site of Hortons Mill, but today that is the location of a salt marsh creek that local people refer to as Morton’s Millpond.

A gristmill and dam stood on that creek at least into the 1930s, but was located well downstream of the mill shown on this map.

That stream, by the way, drains a portion of a large wetlands that is the central feature on the map’s upper left-hand side. It is labeled “Great Swamp called Pocoson.”

John Shoebridge Williams, our mapmaker, may not have realized that pocosin is an Algonquin word for a type of wetlands, not the name of a specific swamp. Today a large part of the “Great Swamp called Pocoson” is part of the Croatan National Forest.

President Lincoln’s Secretary of War

Another important site on the map is Benjamin Stanton’s plantation. The Stantons were among the earliest members of the Society of Friends to settle on the Newport River and they played a leading role in the early growth of the Core Sound Meeting House.

The first local Stanton, Benjamin’s father Henry, also came from Rhode Island. In 1721 he bought land along Ware Creek and Core Creek and established a shipyard, turpentine distillery and brickyard.

Born in 1746, Benjamin married Abigail Macy, who had grown up in a Friends family on the island of Nantucket, in Massachusetts. On the map, you can see their plantation just east of the Core Sound Meeting House.

Benjamin Stanton also bought land in Beaufort and on the islands to the south of Beaufort. In fact, if you go to Beaufort today and look out on the water, much of what you see was once Benjamin Stanton’s property, including Carrot Island and Shackleford Banks.

Benjamin and Abigail Stanton, by the way, were the grandparents of Edwin M. Stanton, who served in the cabinets of three U.S. presidents. Most notably, he was Lincoln’s Secretary of War.

On our map, John Shoebridge Williams misremembered the name of Edwin M. Stanton’s grandfather. In a notation on the bottom center of the map, he has written that “Borden Stanton was a Friend and preacher and grandfather to the Secretary of War.”

He meant of course Benjamin Stanton, who, in addition to his business interests, was also a Quaker minister. Borden Stanton was his brother.

By the time that Edwin M. Stanton was born in 1814, his family was actually no longer Quaker. Like many others, his father had married a woman that was not a member of the Society of Friends. He wed a Methodist and as a result was no longer welcomed among the Friends.

At Harlowe Creek

Before I move on, I want to clarify that this map shows some of the Quaker families that resided between the Newport River and the Neuse River in the 1790s, but not all of them.

The map indicates the homes of the Howard, Dew, Lovet, Hardesty, Stanton, Borden, Williams, Fisher, Sampson and Martin families. While this was a very rural area at that time (and remains rural today), they were far from the only families that resided there at that time.

They were probably the families that meant the most to John Shoebridge Williams when he was growing up there in the 1790s.

However, that list includes only a small part of the local Quakers. The Smalls, Harrises, Browns, Maces, Davises, Chadwicks, Dickinsons, Eubanks and many others are missing.

With one or two exceptions, the map also does not indicate the locations where non-Quakers made their homes. My great-great-great grandparents were among those non-Quakers not shown on the map. At the time that this map chronicles, they were living on Harlowe Creek.

“A Slave Country”

Another omission from this map is even more significant. The map also does not include either the free or enslaved African Americans who resided in that part of Carteret and Craven counties in the 1790s. At that time, they made up the large majority of the population in the area.

In fact, in a memoir that he wrote in 1843 for a periodical called “American Pioneer,” which he published, John Shoebridge Williams referred to the area on this map as “a slave country.”

He did not mean that it was a land where slavery was legal—that was obvious and did not need to be said. He meant that a majority of the local population were African or African American and lived in bondage.

In that memoir, John Shoebridge Williams explained that there were so many enslaved people and so few white children in the area that he had few white neighbors as a child.

He wrote: “my only companion during my first four years was old Quom,” an elderly African man enslaved by the Williams family until sometime in the 1780s, when he was freed.

In Williams’ memoir, Quom comes across as a striking and interesting figure. Williams guessed that Quom was nearly 100 years old when he was a small child, so he may have spent much of his life in West Africa.

Quom had survived the “Middle Passage,” and he may well have been enslaved earlier in his life in the West Indies. Many of the colony’s enslaved Africans had been forced laborers in Jamaica, Barbados and other West Indian colonies prior to being shipped to North Carolina.

Wise and devout, Quom was illiterate but recited Scripture from memory, according to John Shoebridge Williams.

I think it’s also possible that Quom was reciting passages of the Quran, instead of the Bible.

The African elder passed away circa 1794, when John Shoebridge Williams was only 4 years old, and the young boy may not have known the difference between the Bible and the Quran at that age.

Bound for the Northwest Territory

The Quakers resided on that section of the North Carolina coast for three generations. Their days, however, were numbered. In a way this map is a last snapshot of the region’s Quaker community. In 1799, the local members of the Society of Friends began a mass migration to the Northwest Territory.

Within decades, few if any Quakers resided in the area shown on the map. Nearly all emigrated to the Northwest Territory or to the Free States that were formed out of the Northwest Territory.

In 1800, the Northwest Territory covered the lands that later became all or part of the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Most of those Quaker emigrants settled in the part of the Northwest Territory that became the state of Ohio in 1803.

The reasons for their departure were many and varied, but the central issue was their opposition to slavery and the antagonism that their slave-holding neighbors directed against them for, among other issues, paying wages to black workers.

In the years since the American Revolution, the Society of Friends in North Carolina had grown increasingly anti-slavery.

Beginning in the early 1780s, the Yearly Meetings had repeatedly called on Friends to oppose slavery, to manumit their enslaved laborers and to do whatever possible to assist their formerly enslaved workers in getting established as free men and women with their own land and independence.

Some of the largest Quaker slaveholders freed their enslaved workers as early as the period 1781-85. Others did so later. Whenever and however they did it, the local Friends meetings wrestled constantly with the issue of slavery in the 1780s and 1790s.

Politics, financial crises and sometimes war debts factored into some of the local Quakers’ thinking, but ultimately the community’s decision to leave the North Carolina coast came down to slavery.

“That Oppressive Part of the Land”

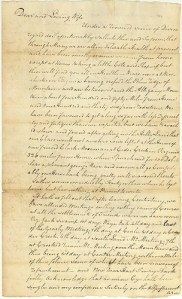

In a letter dated May 25, 1802, one of the Quakers that emigrated from the Core Sound Monthly Meeting, Borden Stanton, recalled how the region’s Quakers decided to go to the Northwest Territory.

“For some years Friends have had some distant view of moving out of that oppressive part of the land,” he wrote.

The local Friends may have considered moving earlier, but they did not act until the late 1790s. At that time, a pair of Quakers from Western Pennsylvania, Benjamin and Joseph Townsend, visited the area’s meetinghouses.

While they were there, they posed, in Stanton’s words, “whether it would be … best wisdom for us unitedly to remove northwest of the Ohio River—to a place where there were no slaves held, being a free country.”

In the following months, the Core Sound Monthly Meeting, which organizationally was over the Clubfoot Creek and other surrounding monthly meetings, commissioned three men to travel to the Northwest Territory in order to investigate the potential for re-locating there.

The three included Horton Howard and his father-in-law John Dew from Clubfoot Creek and Howard’s brother-in-law, Aaron Brown, who belonged to the Trent River Monthly Meeting.

The Trent River Monthly Meeting convened in Jones County, which was located beyond the “Great Swamp called Pocoson” in the upper left-hand side of the map.

The maker of our map, John Shoebridge Williams, was in the first group of Quakers to leave the Core Sound Monthly Meeting and sail for Philadelphia. At the time, he was nine years old.

In the reminiscence that he published in the “American Pioneer” in 1842, Williams wrote:

“In April, 1800, we sailed from Beaufort for Alexandria, in company with 70 other emigrants, large and small, say twelve families.”

From Alexandria they made the long journey by wagon across Virginia and over the Blue Ridge Mountains.

After a delay in Fredericktown, Pennsylvania, they crossed the Ohio River into the Northwest Territory and made their way to the Short Creek region, in what is now Belmont and Jefferson County, Ohio.

When the trio returned to North Carolina, they expressed their enthusiasm for moving as a body to the Northwest Territory.

After hearing the delegation’s report, all or nearly all of the members of the Trent River Monthly Meeting decided to uproot and go to the Northwest Territory. A significant part of the Clubfoot Creek and Core Creek meetings did as well.

Some traveled by ship. Others made the journey overland in wagons and on horseback.

“Like Water through a Breach in a Milldam”

In that 1842 reminiscence, John Shoebridge Williams described his first impressions of the Northwest Territory:

“Four or five years previously five or six persons had squatted and made small improvements. The Friends, chiefly from Carolina, had taken the land at a clear sweep. … Immigrants poured in from different parts, cabins were put up in every different direction, women, children and goods tumbled into them. The tide of immigration flowed like water through a breach in a milldam. Everything was bustle and confusion and all at work that could work.”

A second, larger wave of Friends left Carteret and Craven counties and made the journey to the Northwest Territory in 1802. Others left in subsequent years, mostly going to Ohio, but a significant number also going to Indiana, Iowa and possibly elsewhere.

They were far from alone. They were part of a mass migration of Quakers out of the Slave States. The out-migration of Friends from the area on our map was almost total.

The Trent River Meeting House was “laid down” in 1800. Over the next few decades, the Quaker meetings at Core Creek, Clubfoot Creek and Beaufort all vanished as well. The last to go, the Core Sound Monthly Meeting, was laid down in 1841.

African American Migration to the Northwest Territory

The Quaker migration affected more than the Society of Friends and their meetinghouses, however. Many local black families also migrated to the Northwest Territory.

How many is far from clear. However, it is certain that a significant number of African and African American families moved to the Northwest Territory or, after statehood, to one of the Free States that had previously been part of the Northwest Territory.

In his reminiscence, John Shoebridge Williams referred to two African workers that joined the first wave of Quaker migration to the Northwest Territory.

One was a young man or boy named Minor Edwards. He lived at Clubfoot Creek and left North Carolina with Horton Howard in 1799.

The other was an elderly woman “named Jenny” (no surname listed), who was apparently born in Africa. She relocated to the Northwest Territory in 1802.

In a letter that is preserved in the Forrer-Peirce-Wood Collection at the Dayton Metro Library in Dayton, Ohio, Horton Howard’s daughter Sarah recalled that her father also freed all of the enslaved people that his father had left him in his will.

That was in 1791. “He chose a life of comparative poverty, rather than live in affluence on the produce of slave labour…,”she wrote.

According to his daughter, Howard encouraged those African American families to go with him and his wife Mary when they decided to migrate to the Northwest Territory. Evidently many did so.

In that same letter, Sarah explained, “He gave a small piece of land to each of the men who came with him—they had labored for him and the land was given for that—that they might provide for themselves.”

Benjamin Stanton, Edwin M. Stanton’s grandfather, did much the same. According to family records, he manumitted his enslaved workers sometime in the 1780s.

Benjamin Stanton died in 1798. A year and a half later, his widow Abigail and her six minor children moved to the Northwest Territory. An unknown but sizable number of African American families joined them.

“Stolen from her Country”

Other historical sources indicate that at least one of the Williams family’s enslaved laborers at Black Creek also joined the Quaker emigrants in Ohio, and perhaps far more. That one enslaved laborer may have been the elderly woman named Jenny that I mentioned above.

According to a Williams family story, “a native African woman” raised Richard Williams when he was a small child. Richard was the only son of Robert Williams and his first wife Elizabeth.

“She was stolen from her country by slave dealers. His first language was her dialect, and when he (Richard Williams) was an old man he could repeat many words she taught him.

“She used to tell him the sad story of being snatched from her twin babies which she had left in the shade while she picked berries.

“She lived to a great age, and died in Ohio, where she had been brought with the family when they emigrated there.”

The “native African woman” and other local people of color may have felt as if they had little choice but to go to the Northwest Territory. At that time, North Carolina law did not allow slaveholders to manumit their enslaved laborers except under extraordinary circumstances.

To get around the law, many Quaker slaveholders deeded their enslaved workforce to the Society of Friends, which held them in trust under the law, but in practice allowed them to live on their own, work for wages and otherwise act as free men and women.

However, that arrangement only worked so long as the African American families continued to live in Quaker communities. If the Quaker community vanished, their freedom and safety vanished as well.

Consequently, an unknown but significant number of local “free blacks” followed the Quaker migrants north and settled in the Northwest Territory or later in Ohio, Indiana and other states in the north and west.

Another migration of local free blacks to Ohio occurred later, by the way, but was apparently not connected to this one.

Craven County, in particular, had a comparatively large number of free black residents and many of them emigrated to Cleveland, Oberlin and elsewhere in Ohio between 1835 and the Civil War.

“The Memory of a Child”

I also found the origin of the map interesting. The most important thing to know is that the map shows the Quaker settlements ca. 1799-1800, when John Shoebridge Williams was a child. But he drew the map in 1864, more than six decades after he left Carteret County.

As I already mentioned, John Shoebridge Williams’ family left their home on the Newport River and moved to the Northwest Territory in the spring of 1800, along with that first contingent of approximately a dozen other Quaker families from Carteret and Craven counties.

More than 60 years later, Williams drew the map to share with his children and grandchildren.

To draw the map, he relied on his own memory, but he had not visited North Carolina since he was a child.

To complement his memory, he sought out two others who had lived by the Newport River before moving west. In a letter to his son, John Shoebridge Williams wrote:

“It is from the memory of a child less than 10 years of age, somewhat assisted by that of an old black man and a white man, both of whom, like myself, left North Carolina (Clubfoot Creek) before or at the same time I did and had to think back sixty-three years, for neither of them ever went back.”

The “old black man” was Minor Edwards, whom we met earlier in our story. He was living in Belmont County, Ohio, at the time that John Shoebridge Williams sought his counsel regarding the map.

The white man that Williams consulted about the map was Elias Dew, whom he described as “a Friend preacher, who came (with us) from Clubfoot Creek meeting.”

The map shows the location of the home of Elias Dew’s father, Joseph Dew, on the west bank of Clubfoot Creek. Both father and son relocated to the Northwest Territory.

Where my Great-great-great grandparents Lived

To me this map is important in a number of ways. Above all, to my knowledge, this is the only map that describes the Quaker settlements that flourished on the north side of the Newport River between the 1720s and the early 1800s.

As such, the map is a rare window into an important, largely forgotten chapter in the history of Quakerism in America and helps us to see more deeply into the history of the North Carolina coast.

For me the map’s importance is also personal. It is the earliest detailed map that I have ever seen of the area that has been my “second home” from the time I was born until now.

I grew up mostly 10 miles to the west, but my mother’s family, the Bells, has lived in the area shown on this map since the 1700s. Her ancestors settled originally at Black Creek and later moved a few miles east to Harlowe Creek.

As I mentioned earlier, my great-great-great grandparents were living on the west side of Harlowe Creek in the 1790s, the period that this map covers.

A little later, my ancestors relocated again. This time they purchased land a few miles to the north of Harlowe Creek, adjacent to the Clubfoot Creek and Harlowe Creek Canal. They bought a large tract from the Bordens when that Quaker family headed to the Northwest Territory.

As I write these words, I am sitting in an old farmhouse on that land.

“That’s the Quaker in Her”

The old Quakers are long gone, but some of my neighbors believe that their influence is still with us.

Nearly all of us — the families that were here in the 1700s, at least – are descended somehow from those Friends or their children and grandchildren. The body of the Quakers left and their meetinghouses closed, but many of those that had married outside of the Friends stayed.

Today there are four United Methodist churches in the area shown on this map: Oak Grove, Harlowe, Core Creek and Tuttle’s Grove. The old Quaker families appear again and again in their rolls and minutes.

To this day, if one of the descendants of those families expresses anti-war sentiments, is especially tenderhearted with animals or takes a stand for racial equality, some of my oldest neighbors — I mean the ones up in their 90s — will often say something like, “Well of course, that’s the Quaker in him.“ Or “That’s the Quaker in her.”

In my experience, they don’t necessarily mean it as a compliment — just an observation.

I’ve heard it said more than once about my mother, who in her own quiet way really was a saint.

I don’t really know if my mother’s distant Quaker heritage had anything to do with how sweet and kind she was.

I don’t know if it explains anything at all, in fact, about why she took in every stray kitten and every bird with a broken wing that came her way. Or why she taught her children to judge people by their character, and not by the color of their skin.

All the same, every time someone here tells me, “Well, that was the Quaker in your momma”— or if I hear someone say that about another local person— I think of those long ago times.

When that happens, I always feel a chord of longing deep in my breast. It reaches across my family’s fields and down the old canal that the enslaved workers built so long ago.

It follows the blackwater creeks and the salt marshes, and then it bends and crosses the millponds, down to the shores of the Newport River, Harlowe Creek and Clubfoot Creek, where the Quakers used to live.