The black-capped petrel is somewhat of a mystery. A pelagic bird, it spends most of its time at sea, searching for food in warm waters. At one time it was one of the most common petrels in the Caribbean and along the Atlantic seaboard.

But that was more than 100 years ago and the loss of nesting habitat and predators have pushed the bird to the brink of extinction. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates the population is between 2,000 and 4,000. Other groups cite lower numbers.

Supporter Spotlight

Now, off Cape Hatteras, an effort is underway to get a better handle on just how many black-capped petrels there are, and where they go to breed.

The Fish and Wildlife Service is concerned enough about the species that is has proposed listing the bird as threatened. “…the petrel is a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), meaning it is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range,” the service writes in its assessment.

The bird does fine at sea, but when it’s on land at nesting sites, that’s when problems arise.

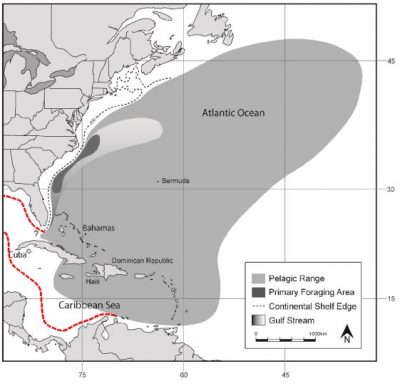

Black-capped petrels burrow into the ground to nest, seeking out mountainous and rugged terrain as the place to mate and raise chicks. Although nesting sites are difficult to identify, apparently at one time breeding populations spread across a number of Caribbean islands.

That is no longer the case.

Supporter Spotlight

“The only known nesting sites are on the island of Hispaniola, the Dominican Republic and Haiti,” said Jennifer Wheeler, co-chair of the International Black-capped Petrel Conservation Group of BirdsCaribbean.

Most of those sites are on the Haitian side of the island, where deforestation and human encroachment have been rampant.

“In particular, the overwhelming dependence of the human population of Haiti on wood-based cooking fuels, such as charcoal and firewood, has caused substantial deforestation in Haiti …” the Fish and Wildlife Service notes.

There are other problems as well.

“Where they nest there was never any native mammalian predators,” Brian Patteson of Seabirding Pelagic Trips said, but introduced species have devastated populations.

“Mongoose is a big problem, but so are rats, cats and dogs,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler estimates there are 500 to 1,000 nesting pairs left, but she points out that getting an accurate count is difficult.

“They’re hard to find. They burrow under trees, under rocks. It’s kind of a needle in a haystack,” she said.

Also unknown is whether there are nesting sites on other Caribbean islands. What project coordinator, the American Bird Conservancy, proposed was to tag black-capped petrels at sea and using satellite tracking see if new nesting sites could be located.

“We’re really interested to see if the birds lead us to new nesting sites,” said Brad Keitt, Ocean and Islands Program Director for the American Bird Conservancy.

Pelagic birds, and especially black-capped petrels, search out warm waters where upwelling creates abundant food. The Gulf Stream off Cape Hatteras is one of their favorite feeding zones.

In Patteson, captain of the Stormy Petrel II, the American Bird Conservancy may have found the perfect person to take the team in search of the bird.

He is the only Outer Banks captain taking people out to the Gulf Stream for birding or pelagic trips, and he’s been doing it for some time.

“We started taking boats out in the ’80s, first out of Virginia, then Oregon Inlet,” Patteson said.

During that time, he’s learned a lot about the behaviors of the birds he’s seeking.

“The black-capped petrel is a pretty skittish bird. It’s the complete opposite of similar looking bird, called a great shearwater – they’re very bold,” he said. “If you have a mixed flock with shearwaters, back-capped petrels will be the first to leave.”

Finding the petrels was not a problem.

“We probably saw 40 or 50 every day,” Patteson said. But, he added, it was the location that furthers the belief there are a lot of them.

“We get a false impression because they’re so concentrated because the Gulf Stream is only 50 or 60 miles across,” said.

With almost 40 years of experience looking for pelagic birds, finding the bird was no problem. Capturing it for tagging had, in the past, proven futile, however. Patteson had been part of an earlier unsuccessful attempt.

“We ran a couple of trips with American Bird Conservancy in August 2012,” he said.

The problem was the 61-foot Stormy Petrel II … or the size of it.

“They’re pretty skittish when it comes to bigger boats,” Patteson said.

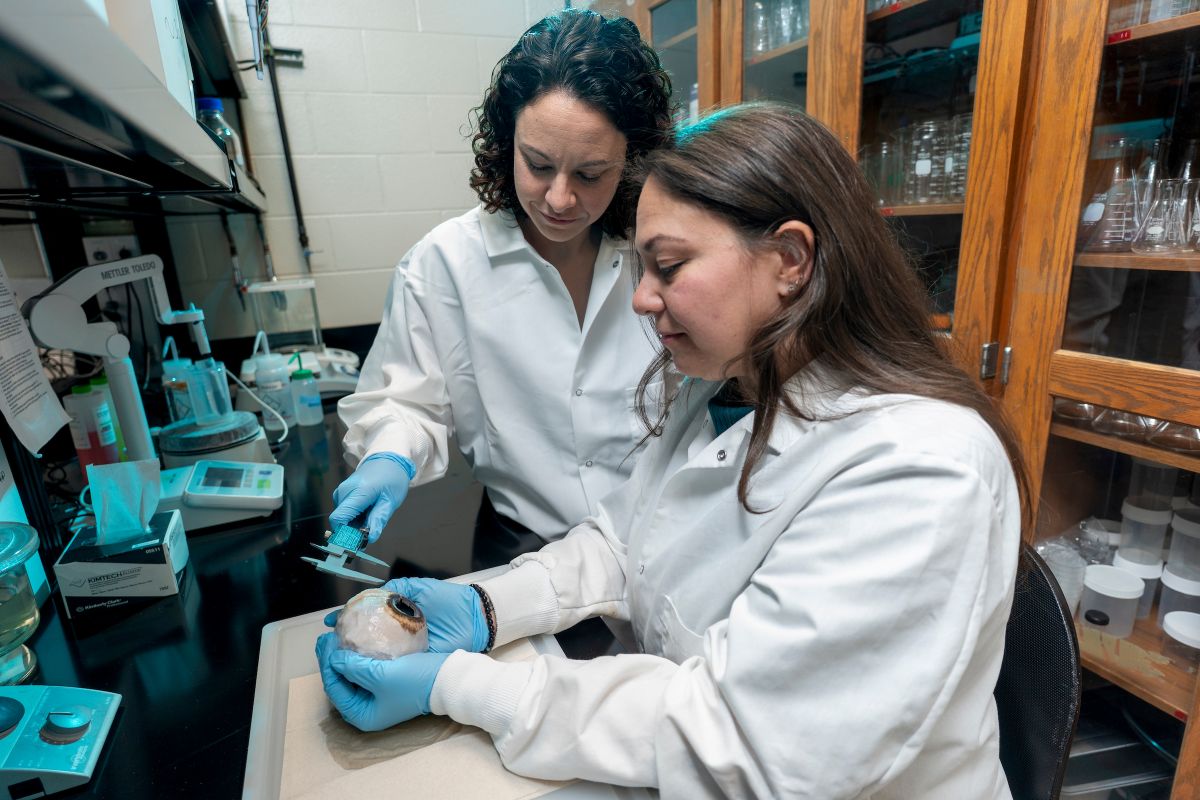

This time though, under the direction of Chris Gaskin, project coordinator for the Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust, they took a 10-foot inflatable boat with them to the Gulf Stream.

“With two guys out there in 10-foot boats they hardly seemed to mind at all,” Patteson noted.

Gaskin used a net that was shot out using compressed air, a technique that has a proven safety record.

“I’ve used this on 250 birds in various parts of the world and never lost a bird,” he said. “Haven’t been any injured with this either.”

The team was hoping to tag 10 birds, but Patteson explained that they were looking for some variations in the birds’ appearance, variations that have in the past been identified.

“There’s basically three variations. There’s a darker one with a darker or blacker face. Then there’s an intermediate one. Then we’ve got one that has less of a cap. Typically it’s a bigger bird,” he said.

The hope is that the variations represent different breeding locations, sites that are not now known.

“The whole idea is (to see) if there are any black-capped petrels on Cuba. If there are any black-capped petrel on Jamaica. If there are any black-capped petals on Dominica. Maybe we’ll find out if we tag enough off Hatteras,” Patteson said.

The project has exceeded expectations, according to team members.

“Fantastically successful,” was Gaskin’s assessment.

“Ten in four days. We’re ecstatic,” Keitt said.

But, Keitt added, this is just the beginning.

“It’s exciting, but really it’s the first step,” he said. ‘The next step is to evaluate and develop a plan.”

Learn More