First of two parts

EMERALD ISLE – As the days lengthen, temperatures rise and the snow birds begin boating north along the Intracoastal Waterway, alert residents in coastal North Carolina just might spot another increasingly common sign of spring: The arrival of a few maverick manatees heading north from overwintering grounds in Florida.

Sponsor Spotlight

Manatee sightings in North Carolina have been reported as early as April and May, but according to state Division of Marine Fisheries biologist Victoria Thayer, marine mammal stranding coordinator for central coastal and northern and central inland North Carolina, “… manatee sightings typically begin in June and continue through late fall.”

These gentle, yet ponderous creatures, which are roughly the size and weight of an Americana bison, are members of a subspecies of West Indian manatee called the Florida manatee, Trichechus manatus latirostris.

As a whole, the species is found from northern Brazil to the southeastern United States. Manatees were drastically reduced in number by centuries of unrestrained hunting before the 1900s. With recovery still in doubt due to reasons that vary in different parts of its range, the species is now listed as “threatened” under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Scientists recognize two distinct subspecies of West Indian manatees. One, the Antillean manatee, Trichechus manatus manatus, occurs in the Greater Antilles and along the Atlantic coasts of Central America and northern South America. A management plan for the subspecies in this region prepared in 2010 by the United Nations Environment Program, or UNEP, found a few signs of recovery in parts of the Caribbean, but concluded manatees may still be declining throughout much its range. The other subspecies, Florida manatees, occur only in the southeastern U.S.

Sponsor Spotlight

At its low ebb in the late 1800s, perhaps a hundred Florida manatees still survived. In 1893, however, the State of Florida mercifully banned manatee hunting in what was one of the first wildlife protection laws ever adopted in the United States.

Since then, the subspecies has eked out a slow recovery despite high levels of human and natural mortality. At the end of 2018, a new abundance estimate of 8,810 animals was announced by scientists with the Florida Wildlife Research Institute and the U.S. Geological Survey.

The new estimate is an encouraging sign of recovery, yet with hundreds of manatees found dead every year in Florida, including more than 820 in 2018 alone, abundance trends could shift quickly. The leading causes of deaths in Florida are collisions with boats, toxins from red tides, and periodic cold stress die-offs.

Because cold temperatures can be lethal to manatees, they do not occur year-round north of Florida. A 2002 study led by Greg Bossart, a veterinarian then with the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute in Florida, identified two types of cold stress syndrome affecting manatees: acute and chronic.

Acute cold stress caused by exposure to temperatures colder than about 50 degrees Fahrenheit can kill manatees within hours or days; chronic cold stress results from exposure to temperatures between the mid-50s to 60 degrees for periods of a few weeks or more.

In spring and summer, however, as temperatures rise, some manatees begin to stray north. And as herbivores eating as much as 150 pounds of aquatic plants per day, roughly 7-15% of their body mass, they do quite well in warm months of the year in North Carolina and other mid-Atlantic States feeding on abundant beds of eel grass, widgeon grass and shoal weed.

Manatee Sightings in North Carolina

A handful of early North Carolina sightings compiled by Frank Swartz in 1995 suggest that the presence of manatees in the state in summer is not a new phenomenon, but since the 1970s, they have become increasingly common. At least a few sightings, and up to a dozen or more, are now reported annually.

In 2010, Erin Cummings, at the time a master’s student at University of North Carolina Wilmington, started a manatee sightings database for North Carolina and Virginia by compiling reliable records from various sources dating back to the 1990s.

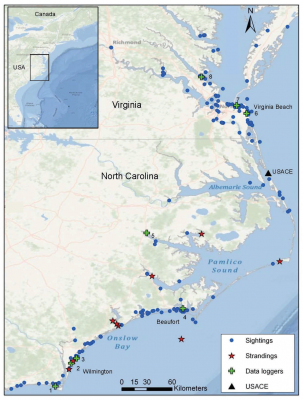

From 1998 through September 2012, Cummings and her colleagues found reports of 98 sightings and nine strandings of dead animals in North Carolina. Except for 2006, when no reports were found, they documented at least one sighting every year in North Carolina, with a clear increase beginning in 2010.

In 2012 alone, there were 30 sightings. Subsequent reports haven’t been analyzed, but they do appear to confirm the increase. In 2018 there were at least 17 reports, including one involving four animals in Lockwood Folly River north of Oak Island in mid-August. Most sightings are from June through October.

For some northbound animals, North Carolina is probably far enough. Here they can linger to feed in the expansive systems of sounds, estuaries and rivers. Most are seen within a few miles of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway near Wilmington and Beaufort, but this probably reflects the greater number of eyes on the water in those areas, rather than true manatee distribution. Some poke far up coastal rivers and have been seen nearly 60 miles up both the Cape Fear and Neuse rivers. Others are occasionally spotted in the ocean close to shore possibly hopping between inlets.

Of course, all northbound manatees don’t stop in North Carolina. Cummings found a slightly larger number of sightings in Virginia, 112 sightings, but those records dated back seven additional years to 1991. Some manatees continue even farther north. In September 2016 a new northern record was logged when a manatee was seen off the southern arm of Cape Cod in Dennis, Massachusetts.

By October, coastal water temperatures along the mid-Atlantic states begin to fall quickly into the low 60s or colder. Manatees that haven’t already begun moving south to Florida need to do so with haste or face a dim survival prospect due to cold stress. A slight uptick in North Carolina sightings in October could reflect an influx of manatees hurrying south from areas farther north. Manatees suffering chronic cold stress become lethargic, form white skin patches, reduce feeding and become emaciated and eventually die by sepsis or cardiac arrest.

In 2018, Kathy Ruge, a resident living on Bogue Sound, was amazed to find a manatee off a community dock Nov. 13 in Bogue Sound. She photographed it milling at the surface. Like many Florida manatees, it had a distinctive old propeller scar on its back.

Ruge said she “had never seen a manatee before, but somehow I sensed it was in trouble and that it was a pregnant female.” Ambient water temperatures had already dropped to the low- to mid-60s and the animal already may have been experiencing early stages of cold stress.

It apparently was trying to warm itself in the sun in a protected corner of the marina. Two other reports in November along Bogue Sound probably involved the same animal.

A manatee believed to be the one photographed by Mrs. Ruge was found dead on Dec. 19 in Beaufort. A necropsy by Dr. Craig Harms, veterinarian and director of the Marine Health Program at North Carolina State University Center for Marine Sciences and Technology, or CMAST, in Morehead City, and Dr. Thayer revealed that it was indeed a pregnant female that likely died of cold stress.

Another manatee likely killed by cold stress also was found that same day off the lower Neuse River. Thayer noted that strandings of dead manatees in the state “typically occur between October and January when temperatures are cold enough to be lethal.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the lead agency responsible for manatee protection, has neither the funding nor local staffing to respond to most distressed manatees outside of Florida. Doing so is a major undertaking requiring considerable funding, mobilizing an authorized rescue team, equipment and facilities for transport and captive care, and finding animals in places suitable for capture and transport.

On rare occasions, however, manatees lingering too long in northern states have been rescued. The animal found off Cape Cod in October 2016 was successfully rescued. It too proved to be a pregnant female. Fearing she was too far north to make her way back to Florida alive, a rescue team formed by the International Fund for Animal Welfare was able to capture and transport it to the Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut for observation and treatment. After a few weeks, she was flown back to Florida by the Coast Guard and released back into the wild in early November.

Next: Why there are more manatees and what to do when you see one