Second of two parts

Supporter Spotlight

EMERALD ISLE — “Rare Manatee Seen in Outer Banks Marina” proclaimed a headline in a June 2018 edition of the Raleigh News & Observer. In recent years, reports of manatee sightings in North Carolina in the state’s media have become particularly notable not because of their rarity, but because of their increasing frequency.

This increase – particularly since 2010 – might be chalked up as yet another sign global warming enabling tropical species to expand their ranges further north. In this case, however, a more important factor may be successful recovery efforts in Florida that have enabled the size of the Florida manatee population to increase.

Now estimated to number some 8,800 animals, up from perhaps 1,000 to 2,000 in the early 1980s, there are simply more Florida manatees available to roam north as Florida’s winter chill gives way to warmer temperatures in spring. Because manatees can’t tolerate waters colder than about 68 degrees for long periods, virtually all manatees in the southeastern United States, including North Carolina, retreat to Florida to overwinter.

Water temperatures throughout most of Florida also regularly dip to the low 60s or colder for weeks or at least days at a time in most winters. In some years these temperatures are reached even in southernmost Florida. Unlike areas farther north, however, the waterways in central and southern Florida have small, localized areas called “warm-water refuges” where water temperatures typically stay at or above 68 degrees during even the coldest winter days. These refuges rarely exceed a few acres in size, and are often no more than a few tens or hundreds of square feet.

Without warm-water refuges, even manatees in Florida would probably be unable to survive. All Florida manatees therefore learn to find and return into them whenever winter water temperatures dip into the mid-60s.

Supporter Spotlight

Manatees are so adept at detecting and following the most minute temperature gradients, Chip Deutch, a manatee biologist with the Florida Marine Research Institute, quipped that “manatees act like heat-seeking missiles” when cold weather sets in.

On the coldest days, up to 80% of all Florida manatees pack into about 15 major warm-water refuges to thermoregulate, or regulate their own temperature, and wait out passing cold fronts. Most refuges are natural springs or power plant outfalls that constantly discharge water 68-70 degrees or warmer.

In southernmost Florida, however, “passive thermal basins” also serve as refuges. These basins are generally smaller areas formed by local hydrological conditions that trap pockets of warm water for at least a few days, or areas with a surface lens of less dense freshwater that insulates a deeper layer of warmer, denser salt water.

Manatees also possess a truly remarkable talent for navigation. They act as if they have onboard GPS systems like those we use in cars to map routes and find the nearest gas station or restaurant. Once manatees find a good source of food, fresh water or warm water, their locations seem to be etched in their memory for future use whenever they happen to be in the neighborhood. Photo identification studies for example, reveal that most manatees faithfully return to the same warm-water refuges winter after winter despite widespread dispersion once water temperatures rise in spring.

The manatees’ inborn system, however, stores and recalls locations of important habitat features, such as warm-water refuges, grass beds, travel corridors and freshwater sources for drinking. These systems are programmed during the first year of life as calves follow their mothers. They enable manatees to trek 1,000 miles or more through murky mazes of channels and shoals, retrace their path within a span of a few weeks, and then repeat it all over again a year or more later.

For example, a manatee named Chessie, who was rescued in the Chesapeake Bay in fall 1994 and flown back to Florida, apparently made repeated visits to southern Virginia. Named after a legendary sea monster allegedly lurking in the famed Bay, Chessie was tracked moving back the Chesapeake Bay the following spring soon after being released into the wild with a satellite transmitter to monitor its movements. His tag unfortunately fell off before making his return trip to Florida, but his last confirmed sighting in August 2001 was made as he moved through the Great Bridges Lock in southern Virginia.

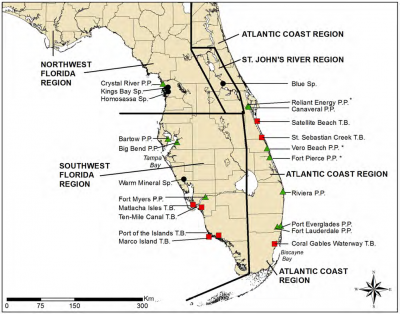

Lifelong ties to specific warm-water refuges, usually those first encountered with their mothers, effectively subdivide Florida manatees into four regional groups or “subpopulations.” Two subpopulations occur on Florida’s east coast – one along the Atlantic Coast south Cape Canaveral and one in the upper St. Johns River – and two on Florida’s west coast – one south of Tampa Bay and the other in northwest Florida around Crystal River. Manatees on the East and West Coasts, which are about equal in number, almost never move from one coast to the other. When they disperse from winter refuges in spring, most animals stay in Florida on their respective coast. However, depending on which coast they overwinter, a small percentage move out of state either north along the Atlantic Coast or west along the Gulf Coast.

Thus, all manatees seen in North Carolina are part of one or both of the two East Coast subpopulations. And because the St. Johns River subpopulation includes less than 20% of all East Coast manatees and tends to stay in the St. Johns River year-round, most, if not all of the manatees in North Carolina are probably seasonal emigrants from the Atlantic Coast subpopulation whose warm-water refuges extend from a power plant outfall in Cape Canaveral, Florida, south to thermal basins around Biscayne Bay (Laist 2005 and 2013).

Thus, the manatees seen each year in North Carolina have likely traveled some 600-800 miles from their overwintering refuges. Travel rates gleaned from manatee tracing studies suggest they could make this trip within two to three weeks.

What You Can Do

Boaters and coastal residents can make important contributions to manatee conservation. Collisions with boats cause 10-15% of all manatee deaths every year and virtually every Florida manatee sustains one or more nonlethal injuries from boat propellers and hull impacts during its life.

Many collisions can be avoided by alert, responsible boat operators. In addition, any action that could encourage manatees to approach people, boats or boating facilities should be avoided. Although seemingly benign, actions that habituate or reinforce manatee attraction to people or boats inevitably leads to situations that place animals at a higher risk of human-caused injury or death.

Precautions consistent with basic principles of safe boating and wildlife viewing can go a long way toward protecting manatees, including the following:

- Immediately call or text reports of injured, entangled, distressed or dead manatees to the North Carolina marine mammal stranding hotline: 252-241-5119.

- Before starting boat engines, check all around your boat to be sure no animals are present. If a manatee is seen, wait for it to pass and then follow a clear path at idle speed away from its location.

- When underway, wear polarized sunglasses and add “manatee footprints” to the navigation hazards you watch out for. Manatee footprints are circular surface swirls a few feet in diameter created by fluke stokes of animals swimming just beneath the surface.

- If you see a manatee or their “footprints,” slow to idle or slow speed and steer clear. Hitting a manatee at speed can cripple or kill the animal, disable your engine, damage the hull, and even injure passengers due to impact jolts.

- Never offer food to manatees.

- Never provide freshwater to manatees and turn off dock hoses not in use.

- Never attempt to touch manatees or approach them closer than about 50 feet.

You can also help scientists learn about manatees by reporting sightings.

In areas such as North Carolina where manatee studies are limited, public sighting reports are especially important for tracking population trends and detecting changes in habitat-use patterns.

Sightings should be reported by email Thayer at vicky.thayer@ncdenr.gov, or by calling or texting the state stranding hotline 252-241-5119.

Most important in sighting reports is accurate information on the time, date, location, number of animals seen, and contact information for the person making the report.

Other useful information would include a description of the animal’s behavior such as feeding, resting, milling around a dock or swimming, the direction of travel, presence of distinctive marks, like healed propeller scars, and if possible, good photos.

Photos showing distinctive scars or fluke notches are particularly valuable for identifying and tracking individual animals. Dead, injured or entangled manatees should be reported immediately to the hotline phone number.

If the manatee population continues to grow and pregnant females return with their calves teaching them of the region’s ample summer food supplies, North Carolina could become a significant summer feeding area for Florida manatees in the not too distant future.