Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski. Cecelski writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

I recently visited with Gerret Warner and Mimi Gredy at a coffee shop in Durham. I had sought out the couple because I had learned that they were making a documentary film about two legendary collectors of American folk music who visited singers and musicians on the North Carolina coast beginning in the 1930s: Gerret’s father and mother, Frank and Anne Warner.

Supporter Spotlight

Along with Gerret’s brother Jeff, they are making the documentary to tell the story of the Warners and of the folksingers and musicians who shared their songs and stories with them.

The Warners traveled all over the Eastern U.S. and sometimes beyond. But I was especially excited because Jeff, Gerret and Mimi are focusing their documentary film on their folk music collecting here in North Carolina, including the Outer Banks, Roanoke Island and other coastal communities.

“A … Tender Devotion to American Folk Song”

At the coffee shop, Gerret and Mimi told me about Frank and Anne Warner and their lifetimes of playing music, preserving folk songs and educating people about American folk music.

I found it a remarkable story. From the 1930s to the 1960s, the couple visited folk musicians across the Eastern U.S.

They both had day jobs in New York City, but folk music was their passion. Every year they spent their four-week vacation on the road, listening to, singing and recording folk songs.

Supporter Spotlight

Often with Jeff and Gerret in tow, the Warners visited mountain hollows, fishing villages and back roads where people still remembered the old hymns, ballads, blues and other American folk music.

Over three decades, Frank and Anne Warner collected more than 1,000 folk songs and stories. In addition to recording them for posterity, Frank sang many of the songs in concerts and put out eight albums.

Anne meticulously documented every interview and recording session. She also wrote the albums’ liner notes.

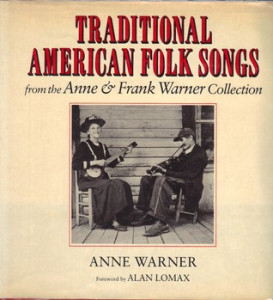

In the foreword to Anne Warner’s book “Traditional American Folk Songs“, Alan Lomax, the Library of Congress’s famous ethnomusicologist, wrote:

“For many years the Warners spent every vacation and every scrap of spare cash on their recording trips. It was a continuous act of unpaid, tender devotion to American folk song and a life-long love affair with the people who remembered the ballads.”

The Warner Collection

The Warner family’s devotion to folk music was also deeply personal. Jeff and Gerret, in fact, both became professional folk singers when they were young.

Gerret eventually stopped singing professionally, but his love of folk music remained strong. Among other projects, he and Jeff teamed up to produce the two CD-set, “The Warner Collection, Volumes I and II.”

After his performing career, Gerret and Mimi settled in Chapel Hill, where they started their own video production and documentary-making company.

Jeff Warner wasn’t able to join us at the coffee shop. He resides in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and continues to perform traditional folk songs throughout New England and beyond. You can learn more about Jeff and his upcoming performances here.

Jeff, Gerret and Mimi also made deep friendships with many of the folksingers that Frank and Anne Warner visited. Many of those friendships continue to this day.

In a way, I think their documentary film is a way to share those friendships, that music, and their devotion to Jeff and Gerret’s parents with the rest of the world.

A Family Project

At the coffee shop, Gerret and Mimi lit up whenever they were talking about Frank and Anne Warner and their music. They explained that they and Jeff had wanted to make the documentary for a long time, but simply had too much else on their plates.

Recently, though, Mimi and Gerret have retired– or at least stepped back a bit– from running their video production company in Chapel Hill. Now they feel that they finally have the time to devote to the project.

Jeff has also been taking time out of his performance schedule to come south and work on the project with them.

“Hang down your head, Tom Dooley”

That day at the coffee shop, we talked a lot about Frank and Anne Warner’s folk music collecting trips here in North Carolina.

Spending so much time in North Carolina was no accident. Frank Warner had grown up in Durham. He also attended college at Duke, in his hometown, where his interest in folklore was nourished by an English professor named Frank C. Brown

Brown was perhaps the state’s leading folklorist in the early 20th century. He founded the North Carolina Folklore Society in 1913 and the Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore, published between 1952 and 1964, is still a central text in the field.

After Frank graduated and moved to New York City to take a job at the YMCA, he and Anne often combined visits to his parents back in North Carolina with folk music collecting trips.

On a collecting trip in 1938, for instance, the Warners visited a man named Frank Proffitt in Beech Mountain. Proffitt taught them an old song called “Tom Dooley.”

The song is about a man condemned to die the next day. The 1866 murder of a woman in Wilkes County had inspired the tune.

Hang down your head, Tom Dooley

Hang down your head and cry

Hang down your head, Tom Dooley

Poor boy, you’re bound to die

In the 1950s, the Kingston Trio and the British skiffle singer Lonnie Donegan made “Tom Dooley” an international hit. Today it can be heard around the world.

“He’s Got the Whole World in his Hands”

Frank and Anne Warner also recorded a landmark version of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” when they visited an African American woman named Sue Thomas in Elizabeth City.

Frank had originally met Sue Thomas at Nags Head on the Outer Banks in the early 1930s or maybe as early as the 1920s.

At that time, he was visiting the old beach resort at Nags Head— in those days, Nags Head was the only resort on the Outer Banks, believe it or not. While he was there, Frank stayed at the Arlington Hotel, a fisherman’s boardinghouse on the south end of the beach.

Sue Thomas resided in Elizabeth City, but in the summers she took the ferry to Nags Head and was the Arlington’s cook. (She had to take the ferry—there were no bridges from the mainland to the Outer Banks yet.)

At the Arlington, Frank and Sue discovered their mutual love of old hymns and folk songs. After she finished in the kitchen at night, she would come out on the porch and they’d sing and play together.

Frank played the guitar, and Sue had a lovely voice, full of sweetness and deep feeling.

One of the songs she taught him was “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

These are the lyrics to Sue Thomas’s version of the song:

He’s got the whole world right in his hands.

He’s got the whole world right in his hands.

He’s got the whole world right in his hands.

He’s got the whole world in his hands.

He’s got the trees and the flowers right in his hands. (3 times)

He’s got the whole world in his hands.

He’s got the crap-shootin’ man right in his hands. (3 times)

He’s got the whole world in his hands.

He’s got the back-slidin’ sister right in his hands. (3 times)

He’s got the whole world in his hands.

He’s got the little bitty baby right in his hands. (3 times)

He’s whole world in his hands.

He’s got you and me in his hands. (3 times)

He’s got the whole in his hands.

The song was an African American spiritual, sung in those days with reverence and a commanding sense of all-embracing consolation.

In the song, after all, God makes room in his hands for the “crap-shootin’ man” and the “back-sliding’ sister.” You’d have to figure God might have room for the likes of you and me, too.

Much later, most performers added a faster beat and hand clapping, making it seem less like a hymn. That’s usually how the song is sung today.

While possibly quite old, the song wasn’t known widely in the 1930s. When she did her research on the song’s origins, Anne Warner found only one previous version in print.

That was in a book of spirituals and other hymns called “Spirituals Triumphant, Old and New,” that was compiled by Edward Boatner, an important African American composer from New Orleans. He was assisted by Willa A. Townsend, a hymnologist and music director in Nashville, Tenn., where the collection was published in 1927.

Boatner and Townsend solidified the song’s place in the canon of African American spirituals. To a powerful degree, Sue Thomas and the Warners would help take the song beyond the church and to the rest of the world.

Singing in Elizabeth City

Years later, in 1941, after Frank and Anne got married, they visited Sue Thomas and her husband Verdon at their home on Poplar Street in Elizabeth City. On that trip, Sue recorded several memorable hymns. One of them was “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

Through the Warners’ recordings, concerts and books, Sue Thomas’s “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” reached the folk music revival that was sweeping the U.S. in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

Over the next few decades, some of the country’s best-known gospel and folk singers discovered “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

Marion Anderson, Mahalia Jackson, Odetta, Nina Simone and many, many others recorded the song.

Singers as varied as Aretha Franklin, Johnny Cash, Big Mama Thornton and Leotyne Price sang the song in concerts.

Mahalia Jackson–who recorded my favorite version of the song– performed it on Sesame Street. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir sang it on national TV. And Judy Garland and her daughter Liza Minnelli sang it as a duet.

Above all, young people embraced “He’s got the Whole World in His Hands.” To them the song said it all: we are all in this together. We are all part of this precious Earth. We are all beloved by God.

Young people sang “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” in Sunday schools, summer camps and civil rights rallies.

Today “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” is sung all over the world. But to an important degree, the song’s popularity goes back to Sue Thomas and Frank Warner singing and playing on the porch at the Arlington Hotel in Nags Head back in 1933.

The Jailhouse Blues

Those are only two of the stories that Jeff, Gerret and Mimi will tell in their documentary film. There are many, many more.

By the way, if you know—or if you have family connections to— any of the folk musicians that Frank and Anne Warner visited here in North Carolina, they would love to hear from you.

They’re looking for more photographs and stories about Sue Thomas, but also about her son J. B. Sutton.

J. B. Sutton recorded two songs when Frank and Anne Warner visited Sue and her husband in Elizabeth City—the Warners referred to his songs as “jailhouse blues.”

The Search for Folk Singers

In addition, Jeff, Gerret and Mimi are looking for more photographs and other information about the lives of several other folk musicians that Frank and Anne Warner visited on the North Carolina coast.

They especially hope to learn more about Eleazar Tillett and her sister Martha Etheridge from Wanchese, Warren Payne from Gull Rock in Hyde County and—well off the coast—Rebecca King Jones from the Ebenezer Church community (Crabtree Creek) between Raleigh and Durham.

Frank and Anne Warner’s original recordings have been preserved at the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center and in the Frank and Anne Warner Papers at Duke University.

When I looked at the online finding aids for those collections, I noticed references to a number of other performers that hailed from the Outer Banks, Roanoke Island and the northern edge of the Pamlico Sound.

They include Capt. John and Awilda Culpepper in Nags Head, Billy Payne in Gull Rock, fiddler Steve Meekins in Kitty Hawk and a whole crowd from Wanchese– Albert and Martha Etheridge, Martha Ann Midgette and at least five members of the Tillett family.

Jeff and Gerret have also staged a musical show featuring the songs that their parents collected. Supported by the N.C. Arts Council, the show is called “From the Mountains to the Sea: The Anne and Frank Warner Collection.”

If you’re interested in the Warners staging the show near you, you can find the show’s contact info here.

Frank Warner passed away in 1978 and Anne died in 1991. I have to think that they would be very proud of their sons and their daughter-in-law for the love and reverence that they are showing toward their life’s work and to folk music in general.

I feel sure that love and reverence will be their documentary film’s heartbeat—and I think that’s a great thing. I look forward to joining them at the premier sometime soon.