Second of three parts

WILMINGTON – Duke Energy will collect and test water samples in Sutton Lake and the Cape Fear River through November.

Supporter Spotlight

“We will extend that effort if data demonstrate it’s needed,” Duke Energy spokesperson Bill Norton said in an email statement.

The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, approved Duke Energy’s monitoring plan. State officials did not respond to questions by press time about whether it has plans for further testing.

‘No Evidence’ of Harm

Duke Energy maintains that only a small amount of ash and ash by-products escaped and no significant harm had been done to the lake or the river.

In a Sept. 19 update the company posted on its website, Duke Energy reported inspectors at the site had identified cenospheres in the lake, “but water sample results show no evidence of a coal ash impact to the lake or the water entering the river.”

Supporter Spotlight

Cenospheres are lightweight, hollow beads made primarily of alumina and silica that are produced as a byproduct of coal combustion.

The company collected water samples over a period of a few days beginning Sept. 16. The test results showed no arsenic reading above 1.11 micrograms per liter.

Testing from three locations in Sutton Lake showed that coal ash contamination was higher than in the river, with arsenic levels reaching as high as 7.37 micrograms per liter.

Coal ash contamination levels are routinely higher than those found in the Cape Fear, according to the company.

DEQ has validated Duke’s test results.

DEQ’s Division of Water Resources took water samples at the breached lake dam Sept. 22 and again on Sept. 25, 26 and 27. The division also took water samples about 1 mile downriver daily between Sept. 25-27.

The lab analysis showed all metals, including arsenic, selenium, boron and other heavy metals associated with coal ash were below state water quality standards.

The one exception was dissolved copper, which “showed a slight elevation” that could be a result of extreme area flooding, according to the state. The agency pointed out that copper levels were the same upstream of the breach.

“A lot of pollutants were released in the flood waters,” said Donna Lisenby, global advocacy manager for the Waterkeeper Alliance.

Junkyards, poultry and hog farms and wastewater treatment plants were among a number of pollution sources swept up by floodwaters that poured into the river.

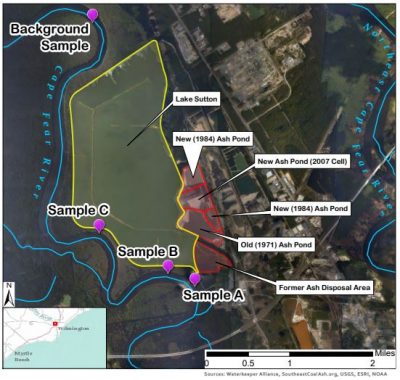

Waterkeeper Alliance was there Sept. 21, the day the coal ash pond breached, releasing its contents into Sutton Lake and spilling into the river.

“That day was when the pollution levels were at its highest,” Lisenby said. “We think the highest coal ash pollution load went into Sutton Lake.”

Waterkeeper Alliance took its samples to Pace Analytical, a certified lab based in Asheville, that showed arsenic levels at 71 times higher than the state safety standard for water quality.

A water sample collected from the largest breach of the lake had an arsenic level of 32.8 micrograms per liter, three times higher than the state’s fish consumption water quality standard of 10 micrograms per liter.

Test results also showed selenium levels of 22 micrograms per liter, more than four times the state Aquatic Life and Secondary Recreation standard, according to the alliance.

Duke officials continue to refute the environmental group’s test results.

“We are pleased that the state’s test results align well with the extensive water sampling Duke Energy continues to perform, demonstrating that Cape Fear River quality is not harmed by Sutton plant operations,” Norton said in an email. “These results, combined with dozens of data points gathered by Duke energy over many days, make it clear that the three samples shared by environmental groups (Oct. 3) are extreme outliers that fail to paint an accurate picture of river quality.”

No Better, Perhaps Worse

Dennis Lemly has been studying environmental risks and aquatic impacts of coal mining and coal-fired industries for more than 35 years.

The focus of his research is selenium, a naturally occurring element that is present in sedimentary rocks, shales, coal and phosphate deposits and soils and concentrated in coal ash.

Exposure in juvenile fish and aquatic invertebrates can cause deformities and stunt growth and reproduction.

In 2013, Lemly, an environmental consultant specializing in ecotoxicology and former research biologist with the U.S. Department of Forest Service, collected and assessed juvenile fish from Sutton Lake during a five-month period.

That was the same year more than 40 years of coal-fired operations ended at the Sutton power station, which has since been converted into a 625-megawatt natural gas plant.

Lemly’s biological assessment showed that discharges from the plant were causing selenium poisoning in young fish and reducing their chances of survival.

Lemly looked at the Duke Energy’s September water sample lab results.

“There’s a big red flag there,” he said. “Selenium in Sutton Lake is higher now than it was in the recent past. It’s not improved since my study years ago. Nothing has improved. Conditions now are no different. The waters are the same.”

More troubling, he said, is the fact that the levels reported by Duke Energy are substantially higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s water quality standard for aquatic life.

The EPA in 2016 updated its selenium threshold for aquatic life. The state has not adopted the EPA’s new standard.

“There’s a major flaw in the premise that Duke can say that they’re meeting the state guidelines,” Lemly said. “The state is behind the curve. The state of North Carolina has not come to the realization for the need to revise their standards and Duke can still claim plausible deniability. Fish are being poisoned and Duke walks away. That whole place is in the Cape Fear River floodplain. It just makes no sense logically. There is no legitimate basis in terms of environmental protection to put a landfill in a flood plain.”

Next: Selenium levels, before and after the flood