When I think of the coast, I think of the crashing ocean waves, the sandy beach and sea oats swaying in a soft sea breeze like a downy feather.

Sea oats are perhaps the most recognizable plants along our coast and a classic remembrance of a summer trip to the beach. Most people can easily identify sea oats and may also be able to identify a few of the coastal trees such as live oak, cedar and pine.

Supporter Spotlight

But there is an abundance of plant life along our coast that is of interest to not only the seasoned botanist but to the casual observer as well. Even though the native habitats of the coast have been fragmented by development we are fortunate that much has been preserved within the national seashores, state parks, wildlife refuges and reserves.

During my early days as a park ranger, I was guilty of not knowing the plants as well as I should. I was more interested in the animals with fur, feathers or scales that could run, fly or crawl. I eagerly learned more about the animals so that I could share the fascinating nuances of our wildlife to park visitors.

Over time, I slowly realized that the plants are just as intriguing as the wildlife. To help me identify plants, I relied on an old text book from my college botany class, “Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas.” A big tome of a book that took a while to weed through to key out a plant. Since I wanted to interpret the coastal plants, I needed a book that narrowed the focus to plants of the barrier islands.

While working at Fort Macon State Park in the late 1970s I received a copy of “Seacoast Plants of the Carolinas,” which was given to me by the author himself, Karl E. Graetz. Two state parks, Fort Macon and Hammocks Beach were used as research sites by Graetz to test the ability of different plant species to help stabilize the mobile sand dunes.

I earned my copy of the book by helping Graetz plant hundreds of plants and rubbing my fingers raw by stripping thousands of sea oats seeds off the stem. Graetz then germinated the seeds in a greenhouse and the following year we would plant them in areas of the sand dunes that were barren of plants.

Supporter Spotlight

While Graetz’s guide was a good source to learn some of the native plants it was primarily designed to assist beach home owners in landscaping their property to prevent the sand from blowing away.

First published in 1973 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and North Carolina Sea Grant, this guide recommended many species that were non-native, invasive and would not be recommended today since they compete with and displace the native species.

But this was the best coastal plant guide at that time and my copy was well used, it now sits in a bookcase, faded, water stained and dog-eared. I haven’t pulled it off the shelf in years.

Recently, the editor of Coastal Review Online, Mark Hibbs asked me to take a look at a new recently published guide on coastal plants and left a copy of it on my desk while I was out of the office.

Recently, the editor of Coastal Review Online, Mark Hibbs asked me to take a look at a new recently published guide on coastal plants and left a copy of it on my desk while I was out of the office.

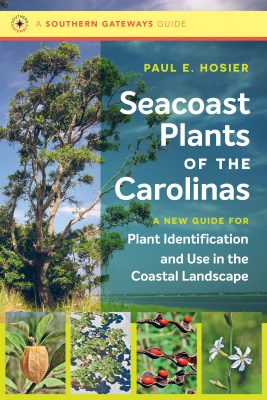

When I returned, I glanced at the handsome cover of the book and saw a familiar title “Seacoast Plants of the Carolinas.” Reading the title, my mind immediately thought of my fingers wrapped in thick white athletic tape. This was the trick Graetz taught me years ago to protect my fingers while collecting the sea oat seeds.

After recognizing the need to update the popular Graetz seacoast plant guide, the North Carolina Sea Grant program spearheaded getting a new version published.

Dr. Paul Hosier, professor emeritus of botany at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, stepped forward to author the new guide. Together, the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and North Carolina Sea Grant provided the funding, editing and distribution of the book.

Long before he actually started writing the book, Hosier compiled a master list of plants from published botanical studies conducted along the North and South Carolina coasts. With the list in hand, he spent countless weekends hiking though all the habitat types of the barrier islands documenting and photographing the plants.

He trekked into the salt, brackish and freshwater marshes, ponds, dunes, shrub thickets, maritime forests and the beach strand. Many times he received wary curious looks from people as he meandered around, head down, looking for plants. With his camera in hand, Hosier went about the extraordinary task of photographing the plants in flower or in fruit with many of the plants featuring more than one image in the guide.

The beautiful color photography, I think, makes it an extremely helpful guide to easily identify the plants in the field. With 745 photographs depicting over 200 plants any green thumb should be able to stroll through the dunes and impress others with their botanical skills.

This exquisite book is more than just a list of plants; it goes into great detail discussing the environment and ecology of the barrier islands and how even ocean currents influence what plants grow where. It reveals how the different habitat types are formed and shaped through the influence of salt spray, temperature, wind, tides and weather. These limiting factors created the adaptations these plants need to survive in such a harsh environment.

As well as a guide with attractive photographs, this book has an amazingly thorough profile of each species listed. The plants are nicely organized in sections listing ferns, graminoids, herbs, vines, shrubs and trees.

Each plant profile lists the common and scientific name, range, habitat, when the plant is in flower or fruit, its wetland status and whether the plant is native or exotic. Each plant is given a thorough description so that if you can’t identify the plant by the photograph, then the details help confirm its identification.

The profile goes on to provide the environmental conditions, such as soil, water and sunlight needs, where the plant will thrive. The wildlife, ecological and human significance of each species is also discussed. Take the common frogfruit, deer like to eat it, it is the host plant for the phaon crescent butterfly and it offers a splash of color if planted along pathways.

The many tables and charts in the book take the guesswork out of how to decide what to plant where in the different plant habitats. In the wake of Hurricane Florence, there is even a table that suggests which shrubs and trees are more or less tolerant to wind conditions.

Truly a labor of love, Hosier has produced more than a guide to the plants of the barrier islands. Anyone that loves these islands with their smooth cordgrass marshes, little bluestem sand dunes and live oak maritime forests will surely benefit by having a copy of this guide on their bookshelf. The guide could also be used as a text book for academic applications in high schools and universities and would be useful to town planners of coastal communities.

While searching the islands for plants, usually in the heat of the day, Hosier would occasionally come across surprises that brought him great satisfaction. A few of the plants are rare and difficult to find. One such plant, seabeach knotweed, caused him to call out “there it is, there it is” when he stumbled across it at the foot of the sand dunes not far from the crashing waves. There were also a few letdowns. If he couldn’t get a good representative photograph of a plant in flower or fruit, it didn’t make the cut to be included in the book. Sorry devil’s walkingstick.

While talking to Hosier about his book, I asked “while cataloging the plants, did you have a favorite?”

His reply didn’t surprise me, “sea oats” he said without hesitation. “When seeing this plant in bloom, it can make my heart flutter and I know where I am.”

Hosier will be in Wilmington in November to make presentations at the Cape Fear Audubon Society monthly meeting 7 p.m. Nov. 12 in Halyburton Park as well as at the Extension Master Gardener Association 11 a.m. Nov. 19 in the New Hanover County Arboretum Auditorium at 6206 Oleander Drive.

Hosier will hold a booksigning in conjunction with Planet Ocean Series meeting 6:30 p.m. Nov. 13 at the Center for Marine Science on Marvin Moss Lane.