HYDE COUNTY – An ambitious plan to restore the aesthetic and natural majesty of Lake Mattamuskeet would require exquisite coordination and cooperation between a community of scientists, public agencies, nonprofit groups, recreational users and residents. But an intensive, 18-month focus on saving the state’s largest natural lake appears to have resulted in that very real possibility.

The draft Lake Mattamuskeet Restoration Plan is set to be presented Tuesday, Oct. 16, in Swan Quarter at the fifth and final public meeting to discuss research findings, ongoing and planned scientific studies and a detailed plan of action.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s just a sense that this will involve total teamwork from all the stakeholders and all the people that depend on the lake,” said Bill Rich, chairman of the Mattamuskeet Watershed Committee who recently retired as Hyde County manager. “It’s just a tremendous, tremendous asset and it has to be saved.”

Supporter Spotlight

In 2017, a partnership of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Hyde County hired the North Carolina Coastal Federation to develop the restoration plan, along with an 11-member stakeholders group that represented different community interests, including farming, hospitality and duck impoundments. A total of 13 meetings were held.

“We’ve always known that this is just a beginning and almost everything in this restoration is to allow us to get funding,” Rich said, “and it’s also the beginning of a long, long effort to clean the lake up.”

The 50-page draft report reflects the complexity of the myriad issues facing restoration of the lake, but also offers clear objectives.

“We tried to look for complementary research we could draw from,” said Michael Flynn, coastal advocate at the federation’s Wanchese office.

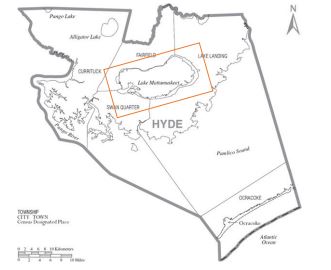

But Mattamuskeet is a unique environment, with numerous public and private jurisdictions, interests and difficult-to-determine boundaries.

Further study of the watershed, its water budget and the hydrological map were some of the suggestions in the plan that could provide more understanding of management of the lake restoration.

A productive first step that could be taken in the near term, Flynn said, would be directing stormwater into a wetland area to allow nutrients to drain into the soil, and then redirect the filtered water to its historic drainage area. Restoring the health of the lake, stakeholders seems to recognize, is the big get that everyone wants – but it will take persistence.

A productive first step that could be taken in the near term, Flynn said, would be directing stormwater into a wetland area to allow nutrients to drain into the soil, and then redirect the filtered water to its historic drainage area. Restoring the health of the lake, stakeholders seems to recognize, is the big get that everyone wants – but it will take persistence.

“It’s a working goal and I think they’re at least going to try,” he said.

Mattamuskeet’s challenges are the cumulative impact of modifications in the land and hydrology, the draft report says.

“Today, areas of the watershed experience chronic flooding and residents have raised concerns about their ability to continue to live and work in the watershed,” it says. “An inability to actively manage the lake water level has created problems for residents and farmers in the watershed, and will only be exacerbated as sea level continue to rise.”

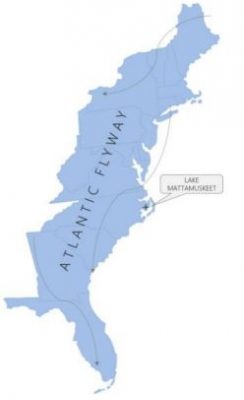

The 40,000-acre lake, the centerpiece of mainland Hyde County, attracts hundreds of thousands of waterfowl – most famously white swans in the late fall and early winter – and is known for its kayaking, fishing, crabbing, duck hunting and, of course, birdwatching. The area, which has a high population of black bear, also is popular with bear hunters.

But for more than a century, Lake Mattamuskeet, which is 6 miles wide, 18 miles long and averaging 2 feet in depth, has suffered more than its share of insults to its ecosystem – from both human and natural causes – resulting in its current unhealthy state. In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency put the lake on its state list of impaired, or more commonly called “dead,” waterways. All of the submerged aquatic vegetation that once covered the lake bed is gone. With no SAV, fewer ducks and swan visit.

But Mike Piehler, director of the University of North Carolina Institute for the Environment in Chapel Hill and a member of the Mattamuskeet science advisory group, said the lake may be impaired, but it still has plenty of life.

“It is in a less preferable state, for sure, but it is by no means dead,” he said, “It remains a valuable ecological resource, but its function is impaired because it is dominated by algae in a way that is not natural.” Although the algae may have toxins, he said, the toxicity has not reached a level where it is dangerous to people or animals.

Piehler, who has studied the lake for years, is hopeful that with local input and support, a scientifically driven process will be able to bring the lake back from the ecological abyss.

“There’s not a simple well-worn path to restoration,” he said. “I think it’s worth the effort to attempt to rehabilitate the lake.”

The lake’s water is plagued by toxic algae blooms, fed by high nutrient levels from fertilizers and bird droppings that drain into the lake. Rising seas make salinity and lake levels harder to maintain. The water has lost much of its clarity due to suspended sediments. Oxygen levels are often low. Heavy rains likely made worse by climate change more frequently flood nearby farmlands and overwhelm drainage ditches with stormwater. Invasive carp have contributed to depletion of the SAV and to other fish species, and invasive plants have clogged the water.

But despite the problems, little has been understood about the exact causes or what would remediate them.

“That’s the reason we launched this watershed restoration project,” Pete Campbell, refuge manager of the 50,000-acre Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge, said in a recent interview.

Campbell said the draft plan, working off scientific and local insights, provides a mix of short-term and long-term objectives that can lead to a manageable approach to restoration of the lake – and importantly, local buy-in. Earlier criticism directed at managers and policy makers from some in the community, he said, has diminished over the course of the meetings of the stakeholders’ team, which included numerous area residents.

“I think people are understanding what condition of the lake is and they want to move forward to make positive changes,” Campbell said. “I think the consensus in the community is the lake is important to them and they want to see the lake improve. It’s an incremental process, and we’re all on the same page, I think.”

A technical working group of scientists and researchers was created in 2013 to start studies of the lake issues, including monitoring. Ongoing or recent research in and around the lake includes waterfowl impoundments’ effects on water quality; carp population impact and control; SAV restoration; and the lake’s input and output of water.

Campbell said that the research will help determine “a path forward with what’s the best bang for the buck.” When the plan is finalized in the near future, funding for projects will become more available from different sources, he said, including federal and state grants.

“The political climate is very good,” Campbell said, “in that our representatives support what we are doing together.”

By looking at complicated issues such as water quality in a holistic way, he said, strategies such as creating incentives to remove nutrients, or devising alternative ways to drain and redirect stormwater from farmland, can foster cooperative solutions. Implementation would be greatly helped by establishment of a more formal structure to oversee the plan, he added.

“It took years to get into this condition, and we can take steps to restore the ecosystem,” Campbell said. “It’s not going to happen overnight.”