Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski. Cecelski writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

On at least two trips to the North Carolina coast, a Greensboro photographer named Charles A. Farrell explored the fishing villages near the mouth of the New River in Onslow County. His first trip was in the fall of 1938, and he visited again sometime in the first half of 1941. On the first trip, he may only have visited Sneads Ferry, a fishing village on the west side of the river.

Supporter Spotlight

On the second trip, he returned to Sneads Ferry, but he also crossed the river to Marines, a village on the east side of the river. I expect that he was drawn there because the War Department had recently announced its decision to take all of the land on that side of the river in order to build one of the largest military bases in the United States — Camp Lejeune.

A few months after Farrell’s visit, the military confiscated thousands of acres on that side of the river, moved out the residents and burned and bulldozed the village of Marines.

Today I’d like to present some of Farrell’s photographs of Marines on the eve of the village’s destruction. I’d also like to share some of what I learned about the village from some of the last people alive who grew up there.

-1-

This photograph was taken in a skiff crossing the river and looking east toward the village of Marines. Melba Marine McKeever, now 92 years old, grew up in Marines and was the person I found that had the best memory of what the village had been like before the war.

Supporter Spotlight

Over the course of several long visits and telephone calls, Melba described for me what she saw in this photograph.

She told me that the pier on the right-hand side of this scene was the center of community life, and the only one in the village.

Before her time, a cotton gin had stood next to it, but she recalled only a spring at the foot of the pier where the local people used to cool watermelons in the summertime. When she was a girl, she and her friends often swam off the end of the pier.

Moving left to right along the shore, we can see a white vacation home on the far left that belonged to the Sleeper family. In the late 1930s, a few non-local families had begun to summer in Marines, and several had hunting and fishing cabins in the area as well.

Moving down the river, a hickory tree rises high above the wood line and, next to it, a large white house. That house originally belonged to Wiley Marine, Melba’s great-uncle and one of the early settlers of the community.

Another of Melba’s relatives, Della Marine, lived in the house when Melba was a girl. Della married Luther Hardison. He was a master carpenter and built furniture and boats. He and Della also took in summer boarders.

In front of their house, we can see William Hanes’ boathouse. He kept his skiff there and went clamming or oystering everyday, weather permitting.

Moving downriver again, left to right, we next see Ollie Marine’s general store behind the pier. Gasoline pumps are beneath the overhang. The little shed in front of the store is his blacksmith shop, where he made flounder gigs, oyster knives and other items.

Ollie Marine’s gristmill was located in a lean-to on the far side of his store, but can’t be seen from this angle.

Electric lines had not yet come to that part of Onslow County. An old automobile engine powered the gristmill, while an array of Delco batteries provided electricity to the store.

First introduced in 1916, the Delco-Light system was an important part of rural life in the early 20th century. While too expensive for most families in eastern North Carolina, the Delco units provided electricity to some individual stores, farms and homes in rural areas prior to the construction of centralized electric systems.

Invented by an Ohio engineer named Charles Kettering, the system involved a bank of large lead-acid storage batteries that, when low on power, was recharged by a gasoline generator.

Behind Ollie Marine’s store stands the village’s other general store, belonging to Edward Smith. Both stores face the village’s main road. A tall pecan tree can be seen behind the Smith general store.

Continuing downriver, we can see a big live oak tree at the foot of the pier, and then the old Baptist parsonage. At the time this photograph was taken, Bruce Hardison, the son of Luther and Della Hardison, lived in the parsonage. Like his father, he was a master carpenter and builder.

The tiny shed in front of the old parsonage was once Ollie Marine’s smokehouse.

Finally, the last house on the right belonged to the Hunt family, summer people from New Jersey.

Outside of the village, the community also had two churches, a school, a sawmill and Joe Wilson’s dance hall, as well as quite a few other homes, farms and hunting and fishing camps.

Not long after this photograph was taken, all of them vanished, like the village, with the coming of Camp Lejeune and World War II.

-2-

Marines, on the New River, 1941. This is a closer view of the right-hand side of the scene in our first photograph. We can see gill nets hanging on spreads over the water, the edge of the village’s pier and several skiffs.

At a community gathering that was held recently on the other side of the river to discuss Farrell’s photographs, a local gentleman named Ray Midgett referred to these boats as New River dead-rise skiffs.

Rowed or rigged with a spritsail and sailed a few years earlier, they were usually equipped with gasoline engines by this time, though all had oarlocks, and they were sometimes still rowed in shallow water. Locals used them for fishing, oystering and generally getting around on the river.

Jess Brown may have built some of these boats. He lived in Marines and was considered the village’s best boatbuilder.

At the time that photographer Charles A. Farrell visited Marines, the white cottage belonged to Seymour and Rose Hunt, a New Jersey couple that had originally come to Marines just for summers, but eventually stayed.

Next to the Hunts’ cottage is the two-story Baptist parsonage, Ollie Marine’s old smokehouse, then the big live oak tree that marked the landing. On the far left, we have a view of the side of Ollie Marine’s general store.

-3-

A young man named Wiley Taylor stands in the bow of a skiff, lantern perched on the boat’s breasthook, waiting, gig in hand, for the light to reflect off a flounder on the river bottom.

Taylor lived at Courthouse Bay, on the north side of the village, but in this photograph he is at New River Inlet, perhaps a half a mile south of the village.

Of his talent with a flounder gig, his daughter, Betsy Taylor Sergomassov, told me not long ago, “He was good at it. Always got them right behind the head.”

His father, a boat captain named Matt Taylor, had died of apoplexy when Wiley was only 9 years old. He dropped out of school, borrowed a little money from a friend and bought a gasoline motor and started fishing.

Betsy recalled, “Despite his lack of education … he was smart. He could build nearly anything, voted Democratic and had a beautiful handwriting.”

During the Great Depression, the young man did a little bit of everything. In addition to fishing, he worked at a Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, camp, which in Onslow County usually meant building fire roads, bridges or drainage canals.

For a time, he also worked on a snag boat on the Tar River, 90 miles to the north, and maybe on other waterways as well.

If Charles Farrell took this photograph on his first trip to the New River, in the fall of 1938, Taylor was a 21-year-old bachelor who maybe wasn’t missed so much when he went flounder gigging at night.

On the other hand, if Farrell took this photograph on his second trip to New River, in 1941, then Mr. Taylor was a married man and had someone to whom he could look forward to sharing his flounder.

Her name was Elizabeth Turner. She hailed from Hadnot Point, further up the river. I published two of Farrell’s photographs of Ms. Turner visiting Browns Island elsewhere on this blog.

They married in 1939. “Both of them poor,” their daughter Betsy told me, “but they made a lovely couple.”

When I published those photographs, I also wrote about the great pleasure of meeting Elizabeth Turner Taylor at a reunion of the people who were dispossessed by Camp Lejeune.

At that time, she was 99 years old and remembered life on the New River as if it was yesterday.

Betsy’s parents told her that Wiley courted her mother by boat, quite possibly the skiff in this photograph. “He liked to take her to visit people who did not have a wharf,” Betsy was told, “because he could anchor and wade ashore carrying her in his arms.”

-4-

James “Jim” Bell splits firewood in Marines in 1941. He and his wife Ella and their children resided on a farm 2 or 3 miles from the village’s center. The 68-year-old made his living by farming, fishing and shingling, but he also did a variety of jobs in the village.

Ollie Marine’s daughter, Melba Marine McKeever, recalled him fondly and remembered that he sometimes worked for her mother’s father, Edward Smith, at his general store.

Mr. Bell was especially close to her Uncle George. She remembers him helping at oyster roasts at his farm, and he also assisted her uncle in making muscadine wine in the late summer.

Melba has also not forgotten the Saturday mornings when Mr. Bell would drive his cart into the village with a load of corn to be ground at her father’s gristmill.

As with the rest of Marines, the military intended to confiscate his home and farm. On the original print of this photograph, Farrell simply wrote, “He’ll have to look for a new home.”

-5-

Two men from the village of Marines fishing with cane poles in a deadrise skiff on the New River, either in the fall of 1938 or early in 1941. The man in the bow is Wiley Taylor, the man in the stern is Ollie Marine. On the horizon we can see Poverty Point and, to the left, Fulford’s Landing, a collection of fish houses, stores and fishermen’s homes that was part of Sneads Ferry.

Ollie Marine’s daughter, Melba, told me that her father was straight talking, kind and giving, not especially warm (at least outwardly), “honest to a fault” and “could do just about anything with his hands.”

In addition to his general store, her father had the gristmill, his blacksmith shop and a little tobacco field. He and his brother had an oyster garden on Courthouse Bay, and he probably fished when the mullet and spot were running in the fall.

People called him “Mr. Ollie.” A newspaper feature story once called him “a walking encyclopedia,” though he had very little schooling.

The daughter of the other man in the skiff, Wiley Taylor, recalled that he came up hard, but was generally well liked. He seemed to make friends easily, even on the other side of the river in Sneads Ferry. That was no mean accomplishment, given the two villages’ rivalry.

“Daddy was friends with the Sneads Ferry boys,’” Betsy told me recently. She explained that he was “one of the few boys from `across the river’ who could get away with courting Sneads Ferry girls.”

More typically, a young man from Marines that courted a young woman from Sneads Ferry, or a young man from Sneads Ferry that courted a young woman in Marines, was likely to find their boat cut adrift the next morning, or maybe discover sand or sugar in their fuel tank.

“Not to mention getting beat up, but that was one of their main entertainments in the 1930s I think,” she told me. In her voice, I could hear her affection for those boys who obviously had some things to work out.

Her mom told her that the young men from Sneads Ferry often crossed the river to go to Joe Wilson’s dance hall, but sometimes wouldn’t even go inside: instead, they’d take on the local boys in the parking lot.

-6-

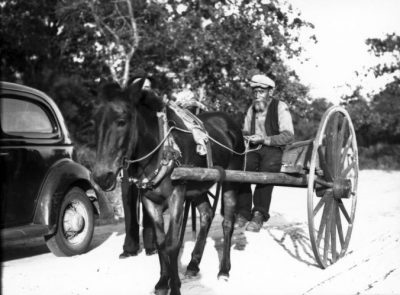

A gentleman traveling in a high-wheeled cart down what is probably the main road into Marines, early 1941. He is holding the reins loosely so his horse clearly knows the way.

I have not yet been able to identify the cart’s driver, but the photographer Charles Farrell indicated that the man’s first name was Reuben. In a brief notation on the back of the original print, Farrell indicated that he “is among those who will have to move.”

-7-

William “Bill” Hanes tonging for oysters on a creek near New River Inlet, just downriver from the village of Marines, circa 1938-41. Hanes wasn’t from Marines, but seemed to fit in well there.

He was from Durham, and, like so many other people over the years, he had come to the coast to recover from what I will call personal troubles and get his life straight again.

He had left his family and a job as an accountant in Durham, and made a temporary home in Marines. While there, he made a living by clamming and oystering and was, by all accounts, reluctant to miss a day on the river.

He also sold bread at Ollie Marine’s store, as well as clams and oysters, usually in exchange for groceries and supplies. I’ve written about Ollie Marine’s store ledgers and what they say about trade and daily life in the village of Marines elsewhere on this blog, by the way.

Hanes seems to have resided in Marines for several years. According to those old enough to remember the village at that time, he eventually got his life together and reunited with his family.

-8-

A final photograph from Marines, early 1941. At the community’s landing on the New River, a trio of fishermen is carrying bags of cornmeal down to their boat. They’ve just come from Ollie Marine’s gristmill, and they’re returning to their homes in Sneads Ferry, on the other side of the river.

Behind them is the river. Gill nets are drying on spreads, and an old dory rests beneath the big live oak tree that marked the landing.

I was not able to identify the two men on the right with confidence, but Ginny Midgett Richardson (who turned 95 earlier this month) immediately recognized the older gentleman on the left.

She used to call him “Pappy.” His name was Louis L. Midgett, and he was her grandfather.

He lived in Sneads Ferry, attended Yopp’s Chapel Primitive Baptist Church and made his living as a fisherman.

When Ginny was young, her grandfather Louis still had a sailboat, most likely a deadrise skiff rigged with a spritsail or maybe an old sharpie — they were traditional wooden boats built for working in shoal waters but could also be used for pleasure.

He took her family to pick “sea kale” (sea rocket, Cakile edentula) on the ocean dunes in the springtime, and he carried them to oyster roasts on the dredge spoil islands around the inlet in the fall.

In the days before “gas boats,” he and Ginny’s father, Lester Midgett, would row upriver and spend all week fishing away from home. They slept in little camps along the side of the river, and they sold their catches in Jacksonville, the county seat, 20 miles upriver.

Ollie Marine had the only gristmill on the lower part of the New River, so the people of Sneads Ferry often crossed the river to get their corn ground in Marines, like Louis Midgett and his two companions have done in this photograph.

In a moving and lyrical memoir called “Memory is a River,” Ginny recalled that her Pappy always had a cornfield.

“What we didn’t eat fresh during the summer, he would store in a crib until it was completely dry, then shell it and have meal for cornbread made from it,” she said.

She described how her grandfather “would row his boat over (to Marines) with the corn and come home with bags of cornmeal.”

Charles Farrell’s small group of photographs proved to be among the last taken of Marines. War was coming, and the construction of Camp Lejeune was looming. Beginning in the fall of 1941, nobody would ever again cross the river to visit the little fishing village on the New River.

A note from the author: This is part of a series that I’ve been doing on Charles A. Farrell’s photographs of fishing communities on the North Carolina coast in the 1930s. In recent years, I’ve been taking his photographs back to the coastal communities where he took them and searching for the stories behind them. You can find my earlier posts on his photographs from Browns Island and Colington Island.