BEAUFORT – What sounds disgusting to most people can be really interesting to scientists. But sometimes, even in the 14-year-old contents of a dolphin stomach, there’s a good backstory of endurance, chance encounters and fate that transcends arcane laboratory analysis.

It’s a fish story that began on May 15, 2001, when a 5-year-old male striped bass was caught in the New Jersey part of the Delaware River, probably between Trenton and Philadelphia, according to Josh Newhard, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service fish biologist at the Maryland Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office.

Sponsor Spotlight

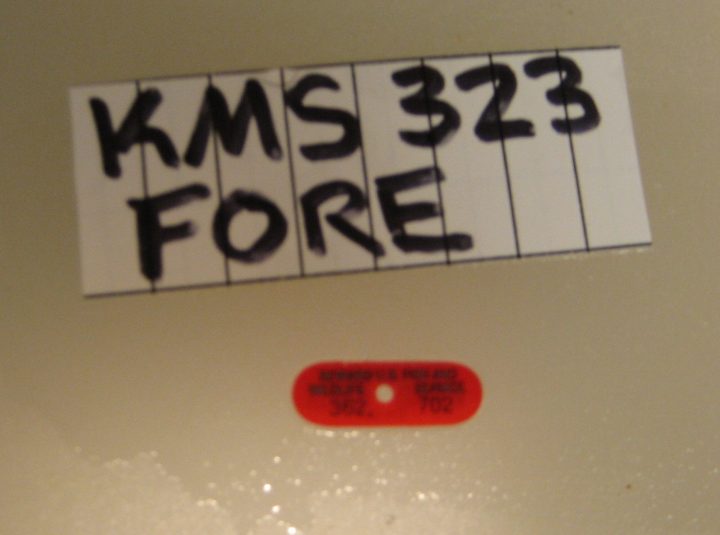

As part of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s cooperative striped bass tagging program that began in 1985, he said, biologists inserted a tag in a small incision under the fish’s belly, with an external tag with the same contact information sticking out. The striper, measured at about 17 inches long, was then released to swim another day.

Nearly two years later, the fish was again caught, this time by a recreational fisherman in the Delaware Bay near Greenwich Township. The angler cut off the external tag and released the fish back in the bay on May 5, 2003.

Not long after, the striper’s luck ran out. On Feb. 25, 2004, a washed-up dolphin – likely a bottlenose – was found dead on an Ocracoke Island beach. Before the marine mammal met its doom, it had made a meal of that hapless striped bass.

But that interesting detail about the striper’s fate wasn’t known until this year, when N.C. State University doctoral student Jacob Krause was examining a backlog of bottlenose dolphin stomachs as part of his research project on weakfish mortality. The stranded Ocracoke dolphin’s stomach, removed during necropsy and frozen in 2004, was one of the many stored at the National Marine Fisheries Service laboratory in Beaufort, awaiting funds to analyze them.

Sponsor Spotlight

While looking earlier this year at the contents of the thawed Ocracoke dolphin stomach, Krause came upon an unusual find: a plastic internal anchor button with a tag number. After contacting Newhold’s office, he learned that the tag had been inserted in the striped bass caught in 2001 in the Delaware Bay.

“We’ve got 120 stomachs, and we haven’t found any tag in any other stomach,” Krause said about its significance.

So what? a non-scientist may think. But the information provided by the tag, minimal as it is, goes beyond dry data – it gives a rare peek into some of the life history of a little-understood animal that roams great distances in huge bodies of water. And by association, it provides information about the dolphin and trophic interaction – essentially, competition for food – in the ocean community.

“It had a large history of moving around Delaware Bay and coming down to Ocracoke,” Krause said about the tagged fish. “Striped bass do overwinter off the continental shelf off North Carolina. It’s fascinating.”

Stripers, also known as rockfish or rock, can grow to about 70 pounds and 5 feet long and can live 30 years. North Carolina is the southern edge of their range.

When Krause called the Fish and Wildlife office to tell them about finding the tag during his research, Newhold said he was intrigued.

“It’s interesting, because to my knowledge, it’s never happened before,” he said. “It’s weird.”

Newhold said it’s not surprising that a dolphin, a top predator, would eat a striper, which was probably about 25 inches long when it became dinner. But what is different is that it so happened to be a tagged fish that had been recaptured and re-released.

“It’s another good example of what we learn from this tag return,” he said. “We’re getting public input. We can learn about pretty interesting things about these species from these tag returns.”

Recreational and commercial fishermen who catch tagged stripers are encouraged to cut off the tag and call the toll-free number to report the date, location and method of capture, according to Fish and Wildlife’s Maryland Conservation Office website. In return, they receive a certificate of participation and a reward. The data provided from reports of more than 85,000 recaptures has helped fisheries managers to better understand migratory patterns of striped bass – for instance, that the fish can swim 500 miles in a month, averaging 16 miles a day.

For Krause, the tag discovery was a diversion from his research focus on finding causes for the population decline of weakfish, a once plentiful fish.

Working with Marine Fisheries research biologists Barbie Byrd and Aleta Hohn at the Beaufort lab, Krause said that 195 stomachs from dolphins stranded over a 10- to 12-year period on North Carolina beaches have been examined so far. Next, an estimate can be made of the effect of bottlenose dolphin predation on the weakfish population.

Krause explained in an email that once he ascertains what percentage of the dolphin diet was weakfish, that number would be multiplied by the estimated dolphin population to see what the impact may have been on the number of weakfish.

“The database is large and has just been completed,” he wrote. “We are just starting to analyze the data.”

As to the less savory work of collecting the data gleaned from the guts, Krause explained in an interview that it takes about five to seven hours to examine each stomach. Typically, by the time the animal is found on the beach, he said, it is pretty rotten, and there’s not much left that’s solid in the stomach. So to figure out what the dolphin has eaten, he looks for the otolith, or inner ear, of a fish – one of the few parts that last a while. With that, he can reconstruct the size of the fish.

Krause said that the otoliths he had identified inside of dolphins – famous for their chirps and calls – are often from vocal fish such as red drum, spot, croaker, spotted sea trout and weakfish.

“It’s interesting that dolphins are keying in on these vocal fish,” he said.

Even though the striper tag discovery strayed from his research, Krause said he appreciates its contribution to understanding just a little more about overwintering sea life on the continental shelf.

“That’s just a big hole in the knowledge gap,” he said.

And hopefully, he added, the dolphin stomach data will help to fill in some other blanks in fisheries science.

“It’s one thing to have everything identified,” Krause said,” but it’s another thing to make a coherent story of it.”