NAVASSA – Residents here are hoping to turn an old wood treatment plant site into one that will honor the townspeople’s heritage, bring in jobs and boost the local tax base.

After months of discussions and meetings, residents, with the guidance of federal and state officials, have drafted four redevelopment concepts for the 245-acre former Kerr-McGee Chemical Corp. treatment plant.

Supporter Spotlight

Though each concept is slightly different, they include common themes.

“One of them is a river walk,” said Richard Elliott, the Multistate Environmental Response Trust project manager of the federally designated Superfund site. “All of them have some type of ferry access. There’s a viewing platform and a kayak launch. All of them have some element of a park-type setting with walking and biking trails.”

There’s also space for a heritage center, a rice field where visitors could see how the historically significant commodity here is grown, light industrial and commercial use.

Residents who attended a quarterly meeting hosted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, Tuesday night were urged to stay open-minded about the concepts.

EPA remedial project manager Erik Spalvins explained that market conditions may change over the time it will take to get some portions of the land ready for reuse. By that time, the community’s priorities may change, he said.

Supporter Spotlight

“Don’t be too fixated and think these are set in stone,” Spalvins said.

As residents have been hammering out prospective plans for the site, federal and state officials continue to investigate the extent of creosote contamination in the soil, in the marsh and in the groundwater of this Brunswick County town.

Creosote is a gummy, tar-like mix of hundreds of chemicals used as a wood preservative.

The wood treatment plant was in operation for nearly four decades, during which time the facility exchanged the hands of a number of companies. The plant operated from 1936 through 1974.

The severity of contamination on and around the site wasn’t discovered until the early 2000s when creosote was found in a swamp by a bridge construction crew.

The site was added to the National Priorities List of federal Superfund sites in 2010.

The Multistate Trust was created in 2011 as a result of the settlement to oversee the cleanup and help develop plans for future use for the property.

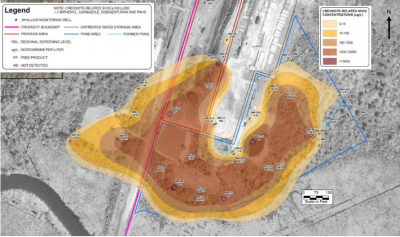

Results of the EPA’s remedial investigation reveal that the highest levels of contamination appear to be in the area where wood logs were coated in creosote and stored to dry and in unlined ponds.

The EPA’s proposed plan is to divide the site into pieces: 50 acres where the wood was stored; 50 acres where the chemical was process and stored in ponds; 30-40 acres of marsh; and 100 acres that is likely free of contaminants.

“This was never used for wood treating,” Spalvins said of the 100-acre area. “It’s probably clean. This area, we’re going to try to administratively cut it out so it’s not part of the Superfund site.”

Officials can then focus on the areas where there is contamination and determine they most effective way to clean and reuse each piece of the site, he said.

Samples routinely taken from dozens of monitoring wells throughout the town are helping officials track a plume of contamination in the groundwater.

“We know pretty much where it is,” Elliott said. “We’ll use that data to try to understand is this contaminated plume growing, shrinking, moving, how’s its behavior.”

So far, the plume has remained in relatively the same area.

Officials are initiating a pilot study to determine which methods will work best to handle creosote contamination in a small area – about 1 to 3 acres – of the marsh.

The revelation that the land, marsh and groundwater have some contamination has consistently raised health concerns from residents who want to know whether eating animals, such as deer, fish and squirrel, they harvest from the land and nearby waters could make them sick.

“It’s extremely low risk,” Elliott said, explaining that the chemical doesn’t bio-accumulate in animals and therefore would not transfer through human consumption.

EPA officials are proposing to dig a series of about 10 trenches within the old wood-treatment area to check for “any surprises” of creosote contamination, Elliott said.

The trenches will about 4 feet deep and anywhere from 150 feet to 300 feet long.

“We have a long way to go before this site’s fully developed,” Elliott said.

The EPA is expected to publish in January 2019 a record of decision documenting the cleanup plan and detailing how the land may be used.